Introduction

More than a century after the death of one of the most translated novelists in the world, it is now possible to establish a history of Vernian studies, not only in French-speaking countries, but also for the entire world. Few writers have been, like Jules Verne, a constant international celebrity, and few have generated a flood of byproducts using his name, his works and his fictional heroes. For example, Nina Ricci, IBM, Nestlé, Toshiba, Vélosolex, Waterman, Capital One credit cards and many other corporations have used the myths and archetypes associated with Verne's name and his works to sell their products and services [1].

Partly because of these commercial products and the many children’s editions of his novels (abridged and mutilated as they were), in both French-speaking and English-speaking countries, Jules Verne continued to be read and his name had not disappeared into a cultural oblivion. Internationally, Verne was and is translated into at least 95 different languages [2] and his readership covers the planet (Figure 1). But it’s really only during the last fifty years that serious scholarly research has been devoted to the author of Extraordinary Voyages and that many discoveries (sometimes both surprising and unexpected) have been made.

Figure 1. Translations of Verne's novels in various languages, like Chinese, German, English, Spanish, Swedish, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Dutch

From the outset, let's define the expression “Vernian studiesˮ, which is also the subtitle of Verniana. The description of Verniana (www.verniana.org/about.html) says: “Verniana publishes original scholarly essays and reviews pertaining to the works and influence of French author Jules Verne (1828–1905).” Verniana provides a publishing venue for research about the sources Verne used, how he wrote, how his life was lived, how he was published and translated, how his “scientific novels” became recognized as mainstream literature as well as literary precursors to the genre of “science fiction,” how recent discoveries about Verne have created new research possibilities about his life and works—all these aspects of Verne’s legacy are part of the “History of Vernian Studies”.

During Verne's Lifetime — Creating the Myth

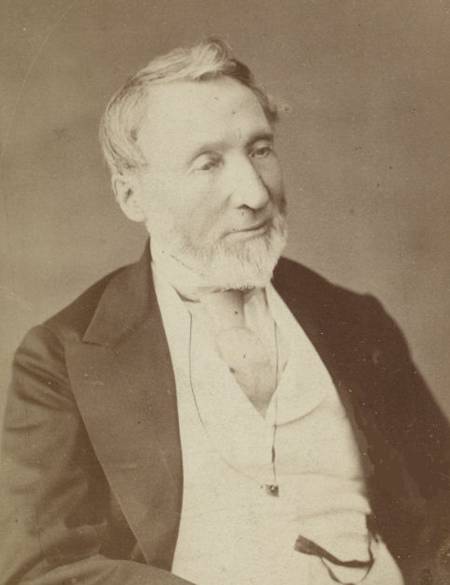

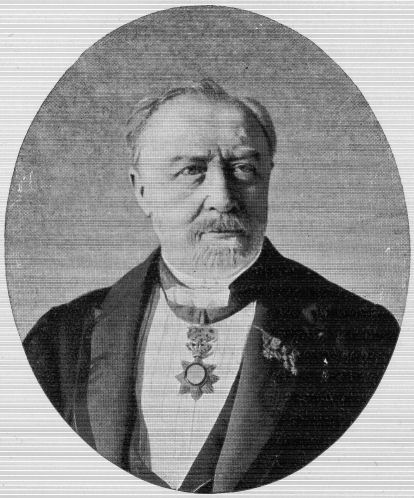

Even during his lifetime, Jules Verne was recognized as a talented writer by geographers and writers such as Vivien de Saint Martin (Figure 2) and Gaston de Saint-Valry [3].

Figure 2. Louis Vivien de Saint-Martin (1802-1897)

Vivien de Saint-Martin, fellow member along with Verne of the Société de Géographie de Paris, was the editor of L'Année géographique (1863-1876), published yearly by Hachette, in which he wrote five reviews of Verne's novels, emphasizing the educational side of these stories. In particular, Saint-Martin noted how

Il est bien difficile que la science et la fiction se trouvent en contact sans alourdir l'une et abaisser l'autre ; ici elles se font valoir par une heureuse alliance.

It is very difficult to mix science and fiction without weighing down one or watering down the other: here they complement each other in perfect harmony (1865, 271). [4]

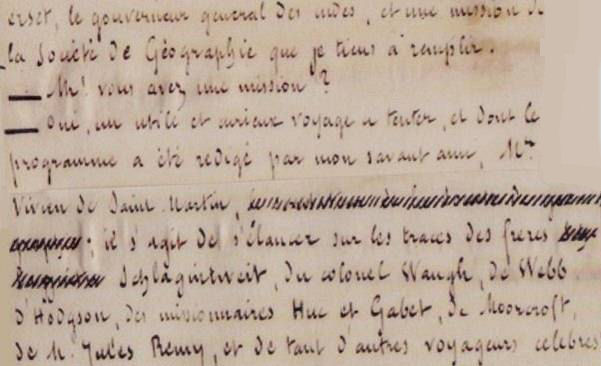

Saint-Martin was mentioned twice by Paganel in Les Enfants du capitaine Grant (The Children of Captain Grant, or In Search of the Castaways) (Figure 3). [5]

|

|

| Pages 45-46 | Page 48 |

Figure 3. Manuscript of Les Enfants du capitaine Grant, volume 1, with the name of Vivien de Saint-Martin in the text

Gaston de Saint-Valry is the first critic to recognize Verne as a literary writer, long before becoming known as a children's author and/or a technological prophet. A contemporary of Jules Verne and editor of the newspaper La Patrie (The Homeland), Saint-Valry underscored the wondrous and fantastic aspects of Verne's novels. His text seems at times surprisingly modern [6]:

Je tente de me rendre compte des principes générateurs de l'originale et poétique création de M. Jules Verne, et je ne crois pas me tromper en indiquant comme le plus essentiel le contraste de ce besoin de merveilleux, toujours latent dans le coeur humain, avec les excessives prétentions scientifiques et positives du temps actuel. II est visible que ce contraste I'a profondément ému. Si j'avais à parler d'œuvres moins connues, moins populaires dans la meilleure acception du mot, j'aurais l'obligation d'insister sur la variété admirable, sur les ressources étonnantes, sur l'étendue d'information et de savoir qui caractérisent cette création romanesque.

A mon avis, depuis Balzac, notre littérature imaginative n'a rien produit de plus original et de plus attachant. M. Jules Verne a imaginé, en effet, des ressorts, des passions et un genre d'intérêt auquel personne n'avait songé; mais il a fait plus, et ceci est la marque du véritable artiste et du créateur: il a donné la vie à des personnages dont la physionomie ne s'oublie plus, qui ont conquis leur place dans cette population idéale créée par l'esprit humain, et au milieu de laquelle l'imagination et la mémoire se promènent avec plus de certitude que parmi le catalogue des personnages réels et historiques. Ne voyez-vous pas vivre le docteur Lidenbrock, du Voyage au centre de la Terre; le fantastique docteur Ox, Phileas Fogg, du Tour du Monde; Michel Ardent [sic !], de la Terre à la Lune; l'ingénieur Cyrus Smith, le colonisateur de L'Ile mystérieuse, le dernier venu de cette amusante encyclopédie ? Enfin, par-dessus tous les autres, ne vous êtes-vous pas attaché à l'énigmatique capitaine Nemo, le patron du Nautilus, un Lara sous-marin ?

I am trying to understand the generalizing principles of the original and poetic creations of Jules Verne, and I think I'm not mistaken in pointing out as the most essential contrast between the need of wonder, always latent in the human heart, and the excessive scientific and Positivist claims of the present time. It is visible that this contrast has deeply moved him. If I had to talk about lesser known works, less popular in the best sense of the word, I would be obliged to insist on their wonderful variety, on their amazing resources, on the extent of information and knowledge that characterize Verne's fictional creation.

In my opinion, since Balzac, our imaginative literature has produced nothing more original and endearing. Jules Verne has imagined storylines, passions and a kind of reader interest nobody anticipated before him; but he has done more, and this is the mark of a true artist and craftsman: he has given life to characters whose countenances cannot be forgotten, who have conquered their place in this ideal fictional population created by the human mind and in the midst of which the imagination and memory walk with greater certainty then among the catalog of real and historical figures. Do you see them almost coming to life? Doctor Lidenbrock in Journey to the Center of the Earth; the fantastic Doctor Ox; Phileas Fogg in Around the World; Michel Ardent [sic] from the Earth to the Moon; engineer Cyrus Smith, the colonizer of The Mysterious Island, the latest addition to this entertaining encyclopedia? Finally, above all others, are you not intrigued by the enigmatic Captain Nemo, the captain of the Nautilus, a submarine Lara [7]?

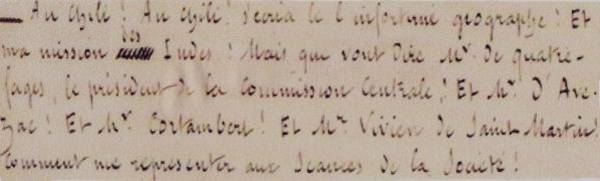

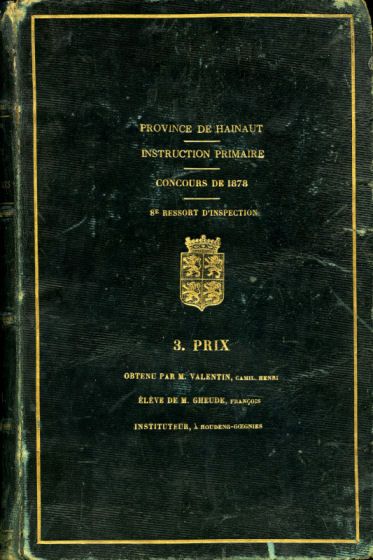

Viewed by the public as a prophet foretelling the future and famous for his fantastic machines, Verne was considered a writer for children already during his lifetime. The youth edition Bibliothèque des succès scolaires (Library of School Successes), published by Hetzel included most of Verne's novels, in the same format as the well-known illustrated in-octavo editions but with a diffrent title page and the binding (Figure 4). Hetzel also sometimes bound the illustrated Verne editions with covers identifying them as official awards for meritorious students of certain French and Belgian schools (Figure 5). This practice helped to reinforce Jules Verne's reputation as a writer for children. Reading the ads and reviews (very often promoted by Hetzel) of the newspapers during Verne's lifetime, it's obvious that Verne, since the beginning, was considered primarily an author for the young and their families.

|

|

|

| Figure 4. Travel Scholarships in the Bibliothèque des succès scolaires | Figure 5. Two bindings as « Livre de prix » (“Price Book”) | |

During the second part of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, it was common practice in France to publish anthologies of short biographies of famous people. Titles like Célébrités contemporaines (Contemporary Celebrities) or Profils intimes (Intimate Profiles) were numerous [8]. The focus of all these biographies was usually on the individuals private lives. Only one can be remembered as looking at Jules Verne as a writer. Georges Bastard wrote the first French biography of the author published after Verne's death, serialized in two issues of a Brittany journal, compiling a text already published as a booklet in 1883 [9]. Dictionaries published during Verne's lifetime also carried articles about him (Lermina, Vapereau) [10]. Pierre Larousse (1817-1875) mentioned Verne in three entries of his Le Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle Larousse, one to Verne's short piece « Les Méridiens et le calendrier », another to the theater adaptation of his novel Le Tour du monde en 80 jours, and the third one to Verne himself [11].

Another journalist who discovered Verne's literary qualities was Marius Topin (1838-1895) who wrote in 1875 [12]:

Voici maintenant le roman scientifique, car, bien que ces deux mots, roman, science, hurlent d'effroi de se voir accouplés, il est impossible de ne pas les associer l’un à l'autre pour caractériser le genre dont M. Jules Verne est l'incontestable inventeur. (375)

And now we come to the scientific novel, although these two words, novel and science, are horrified at being put side-by-side. It's impossible not to connect them together when caracterizing the genre of which M. Jules Verne is unquestionably the inventor.

Three years later, a Dutch writer, Jan Alle Bientjes (1848-1931) compared Verne with Walter Scott and described how he had created a new literary genre [13].

During Verne's later years, several journalists and news reporters interviewed him, usually asking him about his work, his favorite authors, and the method he used to write his stories. Among the most interesting interviews are those conducted by Robert Sherard (who traveled four times to Amiens, once introducing Nellie Bly to Jules Verne) and by Marie Belloc [14]. Today, such interviews are representing a challenge to Vernian scholars, for two main reasons: when the inteviewer reports what Verne said, it's always second-hand information (in contrast to letters, for example, which were written by Verne himself), and sometimes it's difficult to know if an interview is not an adaptation or a plagiarism of another interview published earlier.

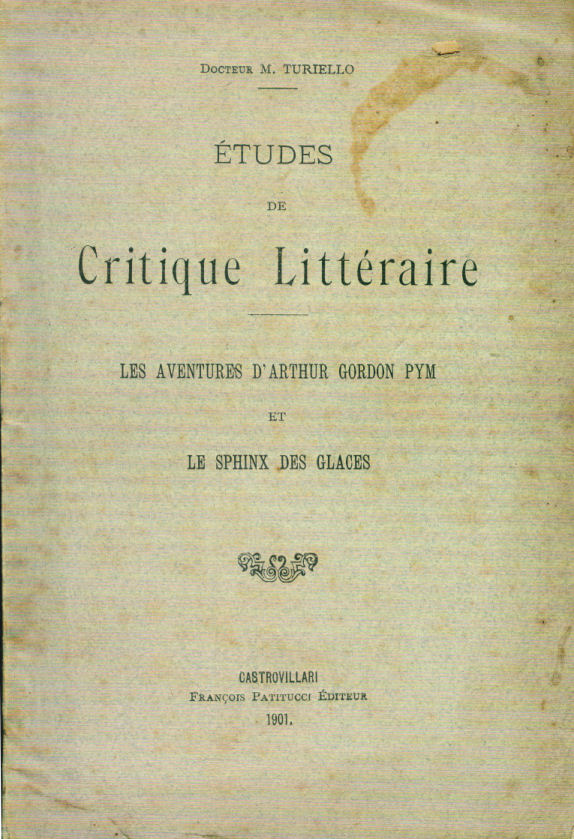

One of the first fans and scholars of Jules Verne was an Italian student in his twenties who exchanged letters with the novelist. Mario Turiello (1876-1965) wrote more than 30 letters to Jules Verne between 1894 and 1904. Jules Verne, well educated and always polite, answered all of them. Turiello published 33 of Verne's letters in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne in 1936 and in two books dedicated to him [15]. Turiello's review and study of Le Sphinx des glaces (The Sphinx of the Ice) is the first monograph dedicated exclusively to one Vernian novel (Figure 6)

|

|

| Figure 6. Mario Turiello (coll. Burgaud) and his study of Le Sphinx des glaces (coll. Dehs) | |

Later, in 1968, three years after Turiello's death, Piero Gondolo della Riva found and bought the letters Jules Verne wrote to his Italian correspondent. They are not identical to the ones published by Turiello 32 years earlier, and Gondolo della Riva published the authentic letters (this time they were 37) in the literary monthly magazine Europe [16]. Verne had no illusions about the quality of translations of his novels. In a late 1897 letter, he wrote to Mario Turiello, saying:

Je ne suis point surpris que les traductions dont vous me parlez soient mauvaises. Cela n'est pas spécial à l'Italie, et en d'autres pays elles ne valent guère mieux, mais nous n'y pouvons rien — absolument rien.

I am not surprised that the translations you've been speaking to me about are bad. This is not particular to Italy and, in other countries they are not much better, but we can do nothing about it—absolutely nothing.

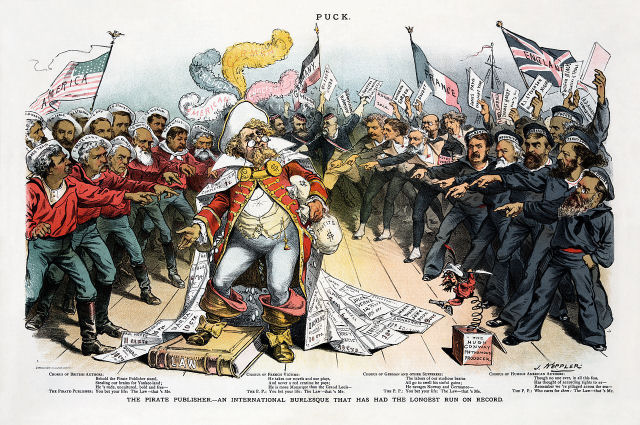

As an echo and confirmation of Jules Verne's words, the satirical journal Puck [17] published in 1886 a cartoon of The Pirate Publisher, illustrating the loophole due to the lack of a copyright law and the authors who suffered most from it (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The Pirate Publisher. Cartoon by Joseph Ferdinand Keppler

On the left, the American writers with Mark Twain. On

the right, the British with Tennyson, Browning, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Lewis Carroll. In the back, the Germans with Freitag and Ebers. And finally, squeezed between

the Germans and the British, the French writers with Emile Zola, Victorien Sardou, Alphonse Daudet, and Jules Verne.

The Anglo-Saxon translations are another perfect example of Jules Verne's words. Soon after their publication in France, Verne's novels were translated into English and flooded the British and American markets. Most of the time, the stories were severely abridged and otherwise bowdlerized by the translators, who sometimes changed their titles as well as the names and nationalities of their characters, and deleted entire paragraphs and chapters which, in their opinion, were too boring to read. In the first English translations published in England, every criticism Verne made against the British Empire and its colonial behavior was censored or suppressed. And, in some cases, the translators even added lenghty paragraphs and/or chapters of their own invention [18].

The Next Five Decades, Until the End of the 1940s — Keeping the Myth Alive and Transforming it into a Popular Archetype

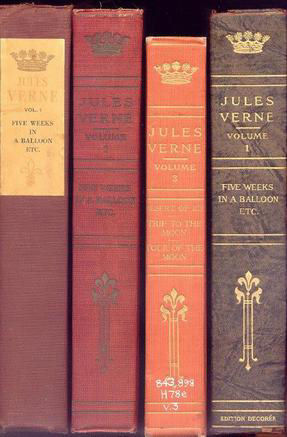

Until the adoption of international copyright laws in the early 20th century, Verne's works were freely translated and (re)published outside of France. In the 1910s, after Verne's death and before WWI, it seems that publishing collections of his novels was suddenly in vogue.

|

|

| Figure 8. The Parke collection (1911) | |

Collections of Verne's most popular novels appeared in English (Figure 8) in the United States [19], in Dutch (Figure 9) in Belgium [20], and in German by Weichert in Berlin who put out 73 volumes between 1901 and 1909. The publisher Saenz de Jubera in Madrid published in Spanish a collection of 14 volumes Obras completas between 1910 and 1914. Every volume included several Verne novels (Figure 10).

|

|

|

| Figure 9. The Van Kalken collection (around 1915) | Figure 10. The Saenz de Jubera collection (1910-1914) | |

In France, the first biography of Verne in book form was published three years after the death of the novelist, written by a friend and colleague from the Academy of Amiens, Charles Lemire (Figure 11) [21]. But it was not until 1928, the centenary of the novelist's birth, that his life's story became frozen in falsehood for more than half a century by a family member, Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe (Figure 12). This biography [22] has been reprinted in successive editions, was translated into several languages and has been for journalists and fans of Jules Verne the standard biography of Verne until his re-evaluation after WWII.

|

|

|

| Figure 11. Charles Lemire (coll. Dehs) and his reliable biography (1908) | Figure 12. Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe's unreliable biography (1928) | |

The first non-Francophone biography was published in 1909 in Germany [23] and the first doctoral thesis on Jules Verne in 1916, also in Germany [24]. The author of the dissertation, Hans Bachmann, researched how Jules Verne (who didn't know English) was using English words and expessions in his novels (Figures 13 and 14). In 1913, the first Verne biography published in Belgium and written in Dutch (Figure 15) was authored by Henri Nicolaas Van Kalken [25].

|

|

| Figure 13. Max Popp (1878-1943) and the first German biography of Verne (1909) | |

|

|

| Figure 14. First doctoral dissertation about Jules Verne (1916) | Figure 15. First Belgian Biography written in Dutch |

Until WWII, few attempts were made to promote the literary study of the works of Jules Verne. On October 2, 1921, a group of ten cadets from the Naval Academy (Royal Naval College) in Dartmouth (UK) founded a society of students to which they gave the name of Jules Verne Confederacy [26]. This group, historically the first to be dedicated to Jules Verne, published a newsletter called the Nautilus. They asked Michel Verne (son of Jules) to be their honorary president. The study of Verne's works was one of the goals of the society.

Brian Taves wrote in 2011:

The most permanent legacy of the Confederacy was the publication of the Everyman's Library edition of Five Weeks in a Balloon and Around the World in Eighty Days in England by J.M. Dent & Sons in 1926 (Figure 16). G.N. Pocock, the former instructor and advisor of the « Julians » (as the teenagers called themselves), ... secured an introduction from the leaders of the Confederacy, K.B. Meiklem and A. Chancellor. Their introduction [27], the best critical overview on Verne in English up to that time, contains one of the first comprehensive bibliographies of editions in English, noting translators. The Confederacy must have known of the issue, because both Cinq semaines en ballon (Five Weeks in a Balloon, 1863) and Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Einghty Days, 1873) were newly rendered into quality translations for this edition. The influence of this volume far outlasted its time, remaining in print for forty years [28].

Figure 16. Title page of the Everyman's Library book

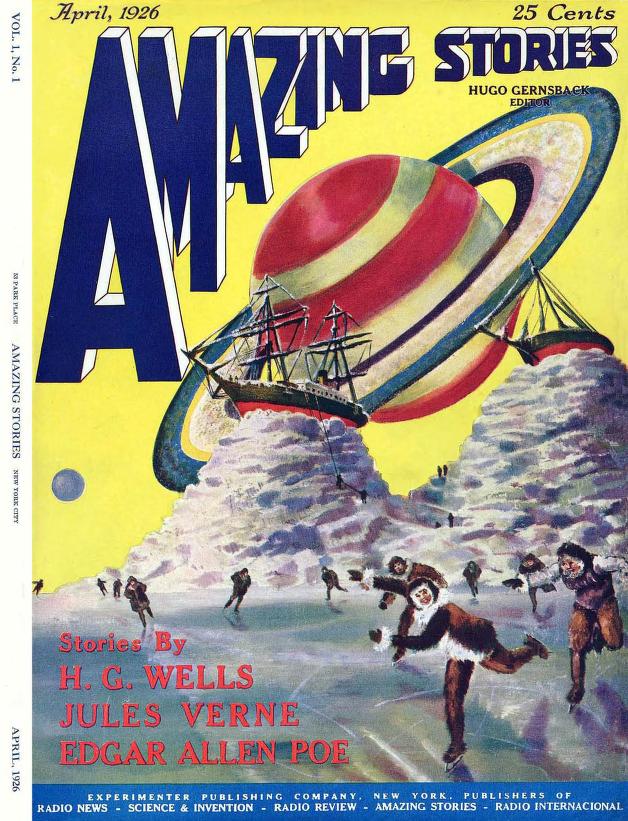

In the first American pulp magazines devoted to the new genre of “science fiction” popular during the 1920s and 1930s, Jules Verne was adopted as a kind of patron saint and revered ancestor. For example, in the first issue of Amazing Stories (Figure 17) in 1926, its editor Hugo Gernsback (1884-1967) defined the genre:

By “scientifiction” I mean the Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Edgar Allan Poe type of story—a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision. ... Edgar Allan Poe may well be called the father of “scientifiction”. It was he who really originated the romance, cleverly weaving into and around the story, a scientific thread. Jules Verne, with his amazing romances, also cleverly interwoven with a scientific thread, came next. A little later came H.G. Wells, whose scientifiction stories, like those of his forerunners, have become famous and immortal [29].

|

|

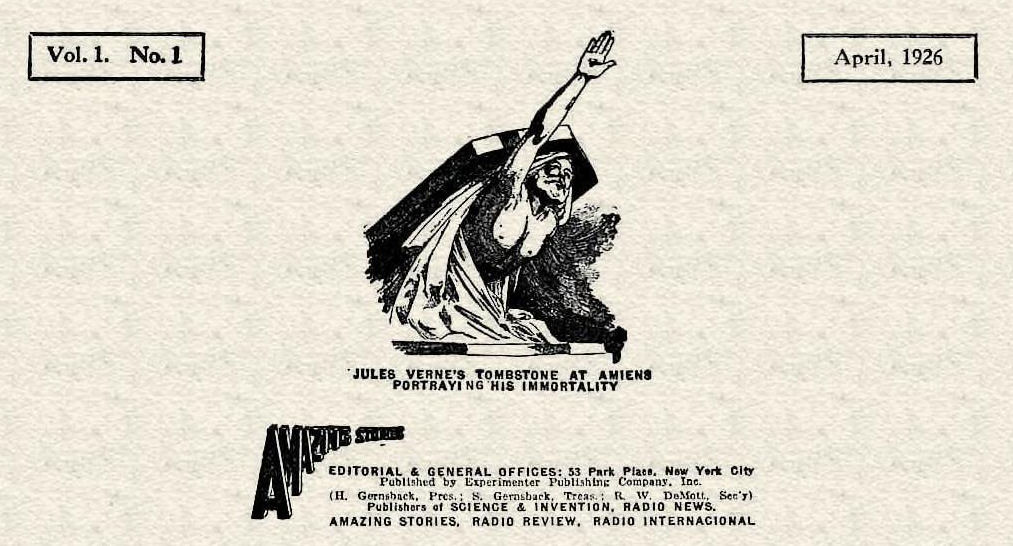

| Figure 17. Cover of the first issue (April 1926) of Amazing Stories | Figure 18. Masthead of Amazing Stories with a drawing of Verne's tomb |

He even included on the masthead of the magazine a drawing of Verne’s tomb in Amiens (Figure 18). The first few issues of Amazing Stories reprinted Verne’s novel Off on a Comet (a poor translation of Hector Servadac).

As mentioned, 1928 was the centenary of the writer's birth, and the Société de géographie (Geographical Society) in Paris (France) celebrated it on January 16, 1929 (Figure 19), with speeches by well-known writers and explorers, including E.-A. Martel [30], Charles Richet [31], and Jean Charcot (Figure 20) [32]. The French Minister of Education Pierre Marraud was present and spoke as well [33].The Sociedade de Geografia (Geographical Society) in Lisbon (Portugal) organized a similar event, but a few years earlier in 1924 to celebrate the 100th birthday of Jules Verne and to combine it with the commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the publication of Cinq semaines en ballon (Five Weeks in a Balloon) [34]. Again, Jules Verne was remembered for having promoted geography, travel, and adventure (Figure 21).

Figure 19. Bulletin de la Société de géographie de Paris, 1929

|

|

|

| Figure 20. Jean Charcot and his polar ship Pourquoi Pas ? | Figure 21. António Cabreira's speech in Lisbon in 1924. | |

In the late 1920s and 1930s, the Italian writer Fernando Ricca wrote several articles, which not only celebrated the centenary of the writer, but also addressed issues as controversial as religion and social justice in the works of Jules Verne [35].

After the publication of the fictionalized biography by Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe, which formed the basis of a Jules Verne mythology for many decades, other biographies appeared in the Netherlands in 1942, in Great Britain in 1940, in the United States in 1942, and in France in 1941, all inspired by the fabrications of Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe [36]. Even today, journalists repeat the unreliable facts and legends invented by Verne's great-niece by marriage.

Adding yet another volume to the tenacious legend of the “prophetic” Jules Verne, a book with a significant title was published in 1936 (Figure 22): Des anticipations de Jules Verne aux réalisations d'aujourd'hui (From Jules Verne's Predictions to Today's Achievements) [37]. The book was translated into Portuguese in 1938 [38]. In 1933, another PhD dissertation is published, again in Germany. It studies the narrative style of Jules Verne [39].

|

|

| Figure 22. Book by Jacobson and Antoni, and its Portuguese translation | |

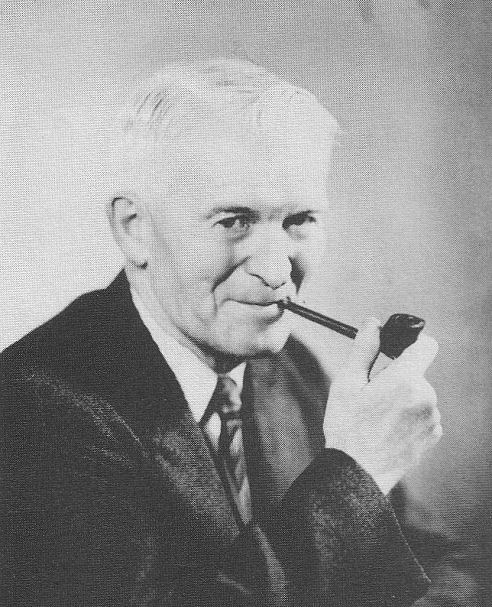

In the United States, Willis Hurd (1875-1958)—who had corresponded with Jules Verne in 1897—gained the attention of collectors and American readers of Jules Verne by publishing an article in Hobbies in August 1936 [40]. In his article (Figures 23 & 24), Hurd had complained about the poor English translations of Verne. The AJVS (American Jules Verne Society) was then officially born in 1940 and held its second meeting in 1942.

|

|

| Figure 23. Willis Hurd | Figure 24. The Hobbies magazine |

After the publication of the Verne biographies by Allott and Waltz (Figure 25), critics such as James Iraldi, Nathan Bengis, David French and Lloyd Jacquet wrote reports detailing the bad quality of the translations and pointing out some inaccuracies in the biographies they were reviewing [41]. Unfortunately, no periodical exists for the first American Jules Verne Society, which didn't survive WWII.

|

|

| Figure 25. The two Verne biographies published in 1940 and 1943 | |

The French publisher Hachette (which bought the Hetzel publishing house in 1914 and owned the copyright to Verne's works) continued until WWII the same marketing strategy as Hetzel, reinforcing Verne's reputation as a writer for the young. Between 1914 and 1966, Hachette inserted very abridged versions of Verne's novels into all its juvenile collections [42], with the Bibliothèque verte (Green Library) as its flagship (Figure 26).

|

|

| Figure 26. Two bindings of the Bibliothèque verte (before WWII) | |

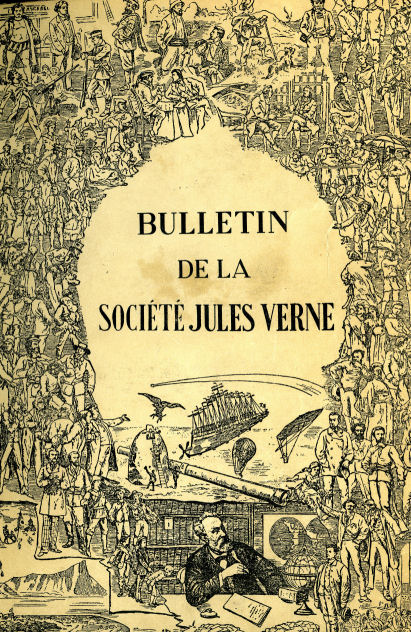

A most important event affecting all future research about Verne took place in March 1935, when Jean Guermonprez (Figure 27), Consul of France in Liège (Belgium), decided to create a society dedicated to Jules Verne. He contacted first Cornelis Helling (Figure 28), a Dutch Verne collector living in Amsterdam (The Netherlands). Both founders were quickly surrounded by supporters and scholars like Raymond Thines, Ivan Tournier, Charles Dollfus, and Edmond Géhu. Two Italian professors joined the small French group, Mario Turiello and Edmondo Marcucci. The bylaws of the « Société Jules Verne » were filed July 31, 1935 in Paris. No such “official” society or club had existed before, so it was unnecessary to have a more precise name, for example adding the word “French” to it.

|

|

|

| Figure 27. Jean-H. Guermonprez (1901-1959) | Figure 28. Cornelis Helling (1901-1995) | Figure 29. Cover of the first issue of the Bulletin |

The membership grew quickly, mainly because a number of celebrities joined the Société: Charles Richet, Louis Lumière [43], Jean Cocteau [44], André Siegfried [45], and Jean Charcot (Paul-Emile Victor's [46] predecessor in the polar explorations). Beginning in November 1935 and for three years until December 1938, the Société published a quarterly Bulletin (Figure 29).

|

|

| Figure 30. First editorial (beginning and end) by Jean Varmond (Guermonprez) | |

Using the pseudonym of Jean Varmond (Figure 30), Guermonprez managed to write and publish in the Bulletin more than 600 pages of well-documented information about Verne. Guermonprez fully deserves the label of first pioneer in research about Jules Verne. WWII stopped the activity of the Société Jules Verne, but Jean Guermonprez corresponded with Cornelis Helling and other specialists of Jules Verne, and contacted the members of the Verne family.

The result of such a “behind-the-scenes” activity was a booklet « Douze ans de silence » (“Twelve Years of Silence”), where all the information collected by Guermonprez during WWII was made available. After Guermonprez's death in 1959, it took several years for the French Verne fans and specialists to come back together and the « Société Jules Verne » was resurrected in 1965, just before Verne's works moved into the public domain in France.

From the 1950s to the mid-1960s — The Beginning of Academic Vernian Studies and Verne's Works Coming into the Public Domain

Until the 1960s, Verne was considered in France as an author for children and/or a technological prophet. Verne's œuvre was not studied in the University and French Literature specialists looked at him with disdain and condescension. Verne stories were viewed as “paraliterary,” on the same level as detective and science fiction stories, and not considered as true Literature (with a capital “L”) [47].

For the first time, in 1949, a French magazine, specializing in literary studies called Arts et Lettres published an issue dedicated to Jules Verne [48]. The writers contributing to this issue (Figure 31) were Michel Butor, Michel Carrouges, Maurice Fourré, Raymond Schwab, Louis-Paul Guigues, Georges Borgeaud, Pierre Devaux, Jacques Boudet, and Antoine Parménie.

The issue is also enriched with a letter by Raymond Roussel [49] to Michel Leiris [50]. Butor's article [51] is especially noteworthy and is often considered as the starting point of literary studies on Jules Verne (Figure 32). It was the first time Verne was recognized and praised by one of the world's most respected writers and critics.

|

|

|

| Figure 31. Cover of Arts et Lettres, 1949 | Figure 32. Michel Butor (1926-2016) and his article, which is often cited as the beginning of the modern Verne studies | |

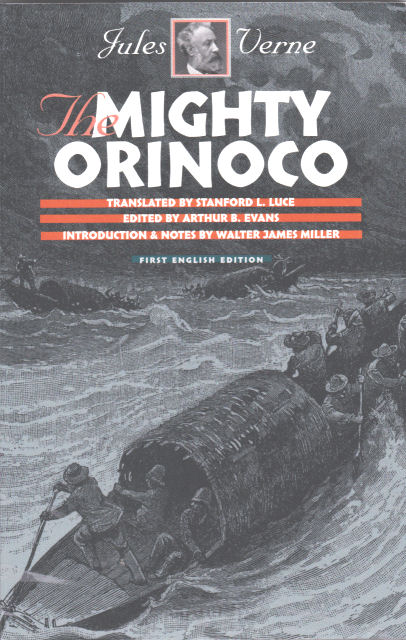

The first PhD dissertation in English on Verne was defended at Yale University in 1953 by Stanford L. Luce, Jr. (1923-2007). It was titled Jules Verne, Moralist, Writer, Scientist and opened the doors of the American academic world to Jules Verne [52]. Luce was a professor of French literature at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and a life-long Verne enthusiast. Following his retirement from the classroom, he translated two Verne novels for the first time into English: The Mighty Orinoco (Le Superbe Orénoque, 2002) and The Kip Brothers (Les Frères Kip, 2007), published by Wesleyan University Press in its Early Classics of Science Fiction book series (Figure 33).

|

|

| Figure 33. Stanford L. Luce and one of his translations | |

The year 1955 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Jules Verne, and it was accompanied by many noteworthy studies of the legendary author. Three magazines devoted one of their issues to Jules Verne: Europe, Livres de France, and Fiction [53]. The highly regarded articles published in these magazines —by recognized scholars such as Georges Duhamel, Bernard Frank, Jean Guermonprez, Pierre Abraham, Georges Fournier, Georges Sadoul, and Pierre Sichel—are still viewed today as an integral part of the critical foundation on which Vernian research is based (Figure 34).

|

|

|

| Figure 34. The three special issues of French magazines of 1955 dedicated to Jules Verne | ||

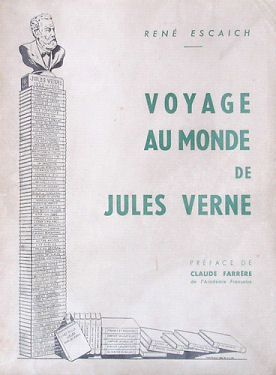

That same year also witnessed the publication of the an important work of serious research on Jules Verne, whose works were still not in the public domain [54]. A well known Parisian lawyer, René Escaich (born in 1909), classified for the first time all the Vernian novels published under the generic title of Les Voyages extraordinaires (Extraordinary Voyages / Journeys), using various thematic criteria such as the nationalities of the characters, places of action, cities, cryptography, madness, etc. His 1955 book proved to be very successful, much more than its predecessor of 1951, published in Belgium with a similar title (Figure 35).

|

|

| Figure 35. Both books by René Escaich (1951 in Bruxelles and 1955 in Paris) | |

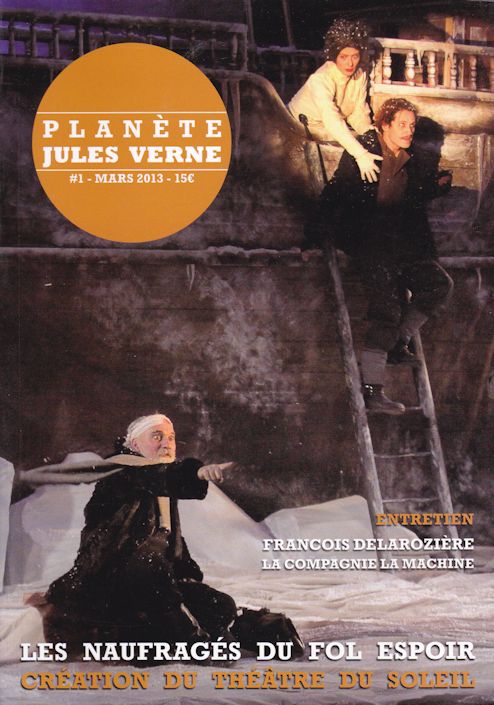

During the late 1950s, the momentum of publications marking the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Verne and the blockbuster appeal of two Hollyewood films by Richard Fleisher (1954, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea) and Michael Todd (1956, Around the World in 80 Days)—the two most popular Verne titles—triggered many more Vernian studies. Some were written by specialists in science fiction like Jean-Jacques Bridenne, Anthony Boucher, and Jacques van Herp ; others by literary scholars such as Marc Soriano and Marcel Moré in France, Robert Pourvoyeur in Belgium or Eugene Brandis in the Soviet Union.

Inaccurate biographies of Verne (most of which were derived from Allotte de la Fuÿe's) continued to be published in the United States [55]. In France the same market was replaced by special issues of youth periodicals, like Tintin or Pif Gadget, repeating the classical stereotype of Jules Verne as a prophet and almost never presenting him as a literary writer. Another element was added to Verne's falsified biography during the 1960s, one that still persists in France today. Esoteric writings began to appear, arguing that Jules Verne was an initiated member of certain secret, mystical societies, and that he had even been in contact with aliens [56].

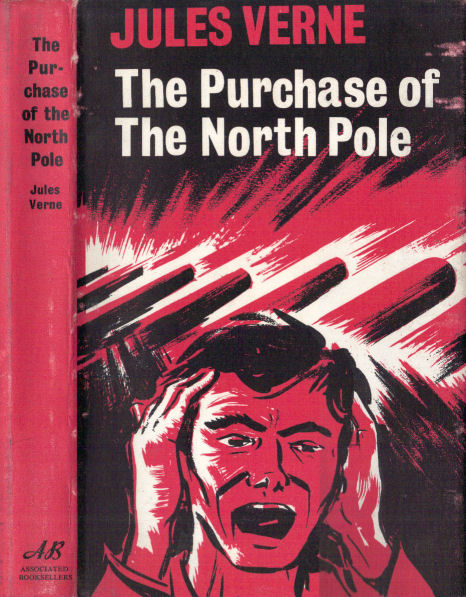

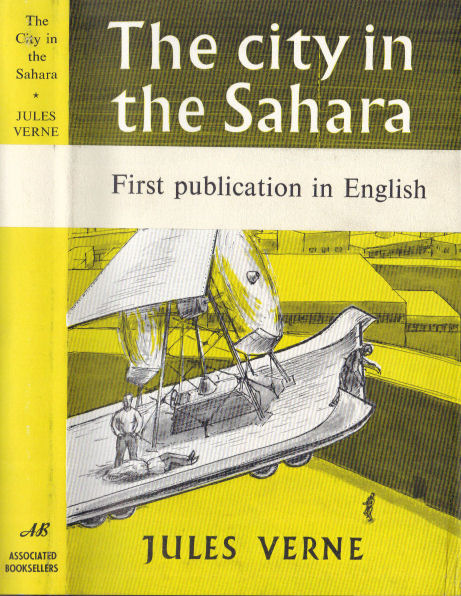

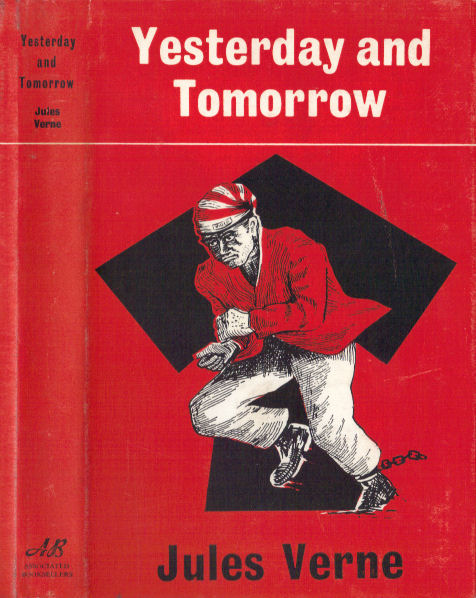

The year 1958 marked a significant milestone in Verne's English-language translations: the beginning of the Fitzroy Edition in both Great Britain and the United States, which was (and still is) one of the most complete collections of the Voyages extraordinaires available in English. British civil servant and writer Idrisyn Oliver Evans (1894-1977) was responsible for the publication of forty-eight Verne stories in sixty-three separate books. He edited and adapted earlier English translations, wrote a preface for every volume, and translated several later Verne titles which were appearing for the first time in English [57]. Although the series was very successful and helped to introduce many Anglophone readers to Verne's works, unfortunately most of the translations in the Fitzroy Edition are not reliable and most of the texts were shortened to make the books in the series of a uniform size (Figure 36).

|

|

|

|

| Figure 36. I.O. Evans and three of the Fitzroy Edition dust jackets | |||

In France, an earthquake-like event, shaking the whole world of Vernian research (even if it was a very small world), took place in the 1960s. One of the most “literary” of the French publishers, Gallimard, put onto the market a book with an intriguing title: Le très curieux Jules Verne (The Very Strange / Curious Jules Verne) [58]. In this revolutionary study, Marcel Moré (1887-1969) applied psychoanalytic methods in his analysis of Verne's life and writings, discovering hidden meanings behind the printed words and revealing personal dramas and fixations much deeper than any Vernian researcher had previously detected. Moré went on to find even more provocative things to say about Verne as he extended his research with a second volume in 1963, again published by Gallimard [59]: Nouvelles explorations de Jules Verne (New Explorations about Jules Verne). Moré was the first Vernian scholar to hint at latent homosexual tendencies in this highly revered French cultural icon, causing a minor scandal in France. But, by his looking beyond the stereotypes that had often characterized Vernian criticism before him, Moré opened the door to serious, high level, academic research about Jules Verne and his œuvre (Figure 37).

|

|

| Figure 37. The two books by Marcel Moré (1960 and 1963) published by Gallimard | |

In 1961, the Collège de Pataphysique (College of Pataphysics) celebrated « en grandes pompes » (in grand style) the 100th anniversary of the conquest of the North Pole by Captain Hatteras (Figure 38). Created in 1948, The Collège de Pataphysique applied the « Eléments de pataphysique » described by Alfred Jarry (1873-1907) in Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll [60]. Jarry was the first prophet of the Theater of the Absurd, followed by playwrights like Eugène Ionesco (1909-1994) and Samuel Beckett (1906-1989). It is easy to conceive that the Pataphysicists have anchored pataphysics [61], from Epicurus to Jarry, in Lucretius, Lucian of Samosata, Zeno of Elea, Béralde de Verville, Rabelais, Cyrano de Bergerac, Cervantes, Jonathan Swift, Lichtenberg, Marcel Schwob, Lewis Carroll; and in contemporaries of Jarry, Jules Verne and Erik Satie; and later, coming after Jarry, Arthur Cravan, Raymond Roussel, Marcel Duchamp, Julien Torma, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, the Marx Brothers, Jorge Luis Borges.

|

|

| Figure 38. Cover and title page of issue 16 (1961) of Virdis Candela, dossiers acénonètes du Collège de Pataphysique, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the conquest of the North Pole by Captain Hatteras | |

Together with the three French Vernian focal points (the Société, the Documentation Center in Amiens and the Bibliothèque / Musée in Nantes), following the path opened by Raymond Roussel (1877-1933) with his book Comment j'ai écrit certains de mes livres (How I Wrote Certain of My Books) [62], the pataphysicists—with chapters now in all continents—discovered in Jules Verne a precursor of the modern novel, having influenced the 20th century French literature, including the Surrealists, and its successor the Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle—Workroom of Potential Literature), as well as authors of the nouveau roman.

From the Mid-1960s to the 1970s — The Availability of Obscure Texts and the Development of New Research Directions

The first step towards making more of Verne's personal writings public was made in 1965, when the heirs of Pierre-Jules Hetzel (the father, 1814-1886) and Louis-Jules Hetzel (the son, 1847-1930) donated to the Bibliothèque nationale de France (French National Library) all the private papers of the two publishers. Among these papers were hundreds of letters written by Jules Verne to his publishers (Figure 39).

Figure 39. One of Verne's letters donated in 1965 to the National Library of France. It was written to Hetzel, on a Friday, from Liverpool. Verne was on his way to New York with his brother Paul, ready to board the Great-Eastern. The number 51 in the upper right corner was given to this letter by the librarian who took care of the collection of the letters. The mention on top « vers le 20 mars 1867?] » ([around March 20, 1867?]) was not written by Verne, but also by the librarian charged to put the letters in order.

It was the beginning of making available to Vernian scholars important primary materials that had not been accessible before that time.

The first step was to catalog more than 700 letters and to put them in a relative chronological order. The job was not easy and Verne was the first to blame, because he almost never correctly dated his letters. He just often wrote : « Amiens, lundi » or « Amiens, 20 juillet » (“Amiens, Monday” or “Amiens, July 20”) which didn't give any precise indication of the date when the letter was written. The librarian in charge of this cataloging did the best she could and some scholars could consult the letters. It was not an easy task. The letters were put on microfilm and copies exist in several collections [63]. It took more than 30 years to get these letters published. Eventually, three Vernian scholars, Olivier Dumas, Piero Gondolo della Riva, and Volker Dehs succeded in making them available to the public between 1999 and 2006 [64]. This last step, covering almost 10 years, involved reading in detail these letters, connecting them with facts and events of Verne's life and deciding what the chronological order was. The three editors had a very good knowledge of Verne's life, as well as the lives of the two Hetzels. The biography of Hetzel published in 1953 was one of the ressources they were able to use [65]. One of the authors of that biography was a granddaughter of Pierre-Jules Hetzel.

After Verne's works entered into the public domain, two Swiss publishers rushed into the breach: « La Nouvelle Bibliothèque » in Neuchâtel and « Rencontre » in Lausanne. The first collection contains a dozen volumes only [66], all published in 1963, all prefaced by the polygraph Maurice Métral whose affirmations about Verne have not much to do with facts and were often the product of his imagination.

The second collection still remains the only complete modern French-language edition of the novels and and other writings by Jules Verne. Published between 1966 and 1971, this collection of 49 volumes is so comprehensive that it deserves some commentary (Figure 40).

|

|

| Figure 40. Cover and back of the « Rencontre » volumes | |

Two volumes in the collection contain the early texts of Le Comte de Chanteleine (The Count of Chanteleine) and « Edgar Poe et ses œuvres » (”Edgar Poe and his works”), as well as many other works never republished since Verne's lifetime. The first nine volumes have a preface written by Gilbert Sigaux (1918-1982), all others by Charles-Noël Martin (1923-2005). Until the 1960s, Martin was well known as a nuclear physicist and popularizer of nuclear physics. He wrote a biography of Albert Einstein, with whom he exchanged letters [67].

When Sigaux became unable to write the prefaces for all the Rencontre volumes of their Verne collection, Charles-Noël Martin was asked to continue the task.

Martin always liked Verne but never became a specialist of him before the 1960s. With his enthusiasm and meticulous care, he unveiled a lot of unknown aspects of Verne's life and works (the contracts between Hetzel and Verne, Verne's love affairs, etc.) which he discussed not only in his prefaces for Rencontre, but also in two biographies of Jules Verne published in 1971 and 1978 [68]. He added to that many articles about Verne, and another PhD dissertation [69], at the age of 56 (Figure 41). Through all his writings (prefaces, biographies, thesis, and articles), Charles-Noël Martin, after Jean Guermonprez, will be forever remembered as the second great research pioneer in Vernian Studies.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 41. Charles-Noël Martin (1923-2005) and his three main Vernian publications: two biographies and a PhD dissertation | |||

In the mid-1960s, the Livre de poche (/cite>Pocket Paperback), now that Jules Verne's works were in the public domain, began to reprint many of Verne's novels, beginning with Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days), using the same layout, pagination and illustrations as the Rencontre collection. Every volume had a unique cover until the 1990s when the collection began to be more uniform with its characteristic red frame and black and white illustration in the center (Figure 42). After so many years where Verne was on the market only in very expensive editions or in badly illustrated and truncated copies in Francophone countries, finally there was a collection making Verne's novels available in cheap paperbacks, with the Hetzel illustrations and a complete text. Every volume ended with an eight-page biography of the author.

|

|

| Figure 42. The Livre de poche as it was available in the 1960s and in the 1990s | |

In parallel with the availability of better Vernian texts, another catalyst for the Vernian research was the revival of the « Société Jules Verne » in 1965. It was revived under the leadership of Joseph Laissus (1900-1969), who was soon replaced by Olivier Dumas, who led the Society until 2012, when he was replaced as President by Jean-Pierre Albessard (Figure 43).

|

|

|

| Figure 43. The three presidents of the « Société Jules Verne »: Joseph Laissus, Olivier Dumas, Jean-Pierre Albessard | ||

For more than 40 years, Dumas made the « Société Jules Verne » the major crucible of Vernian research.

Jean Guermonprez had passed away in 1959, so Cornelis Helling and Etienne Cluzel maintained a continuity with the «old» (pre-WWII) Société. In 1967 the Society began publishing a new series of the Bulletin, with a periodicity of four issues per year. The 150th issue appeared in 2004 and, after celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Société, the 200th issue of the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne should be published in April 2019 (Figure 44).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 44. Covers of the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne since 1967. The last cover is issue 100 with the first publication of Edom, which makes it an original edition | |||

Vernian researchers and scholars, worldwide, became members of the Société, which was until the 1990s, almost the only venue offering a platform to share their discoveries. Through the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, not only French, but also Germans, Belgians, Italians, Spaniards, Swiss, Americans, et al., published the results of their research [70]. Several well-known personalities from the literary and scientific worlds, often academics, supported the efforts of the Société Jules Verne: André Brion, Joseph Kessel, André Chamson, François Mauriac, Raymond Queneau, Paul-Emile Victor, Norbert Casteret, Haroun Tazieff, Jean Orcel, Theodore Monod, and Pierre Versins, which were joined by Verne specialists such as Francis Lacassin, Jean Chesneaux, and Charles-Noël Martin.

Concurrent to the activities of the Société Jules Verne, both French and non-French scholars and researchers were beginning to study Verne's works and life and publish monographs, that presented new aspects of Verne's writings. In Frence, in the footsteps of Michel Butor—one must recognize the work of Marie-Hélène Huet, Ghislain de Diesbach, and the important contribution of Michel Serres [71]. Biographies were published in Czechoslovakia [72], in the United States and in Great Britain.

Alongside the Société Jules Verne, another Vernian research group was born in France. In 1972, in Amiens, Daniel and François Compère used the garage of their family home to create and develop the Centre de documentation Jules Verne (Jules Verne Documentation Center). The whole Compère family was involved in the project and after a few years, Daniel and François were replaced by their parents, Cécile and Maurice who transformed the Centre de documentation into a such an important center of information, that twenty-five years later, it was still in communication with researchers worldwide, offering a collection of more than fifteen thousand documents and memorabilia, covering a spectrum from a simple photograph or a few lines in a newspaper clip to a biography of Jules Verne in Russian (Figures 45 and 46).

|

|

| Figure 45. Maurice (1919-2002) and Cécile (1921-2006) Compère in the courtyard of the “tower” house, 2 rue Charles-Dubois in Amiens | Figure 46. Daniel Compère |

A third French research group was set up, this time in Nantes, where the Bibliothèque municipale (Municipal Library), directed from 1962 until 1987 by Luce Courville (1923-2004), in collaboration with Colette Gallois and Claudine Sainlot, hosted in the mid-1970s the Centre d'études verniennes (Center for Vernian Studies) under the direction of university professor Christian Robin (Figure 47).

Already in 1955, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Verne's death, Nantes had organized the first Verne exhibition in France. It was followed by many others in 1963, 1966, 1970 and 1975. The project to have a Jules Verne Museum in Nantes began in 1955 and became a reality in 1978, with the celebration of his 150th birthday. Overlooking the Loire river, close enough to Verne's birthplace, and even closer to the Chantenay house where Jules and Paul played during their youth, the Musée Jules Verne is a mandatory stop for every Verne fan visiting France (Figure 48).

|

|

|

| Figure 47. Christian Robin | Figure 48. The Jules Verne Museum in Nantes, entrance and side overlooking the Loire river | |

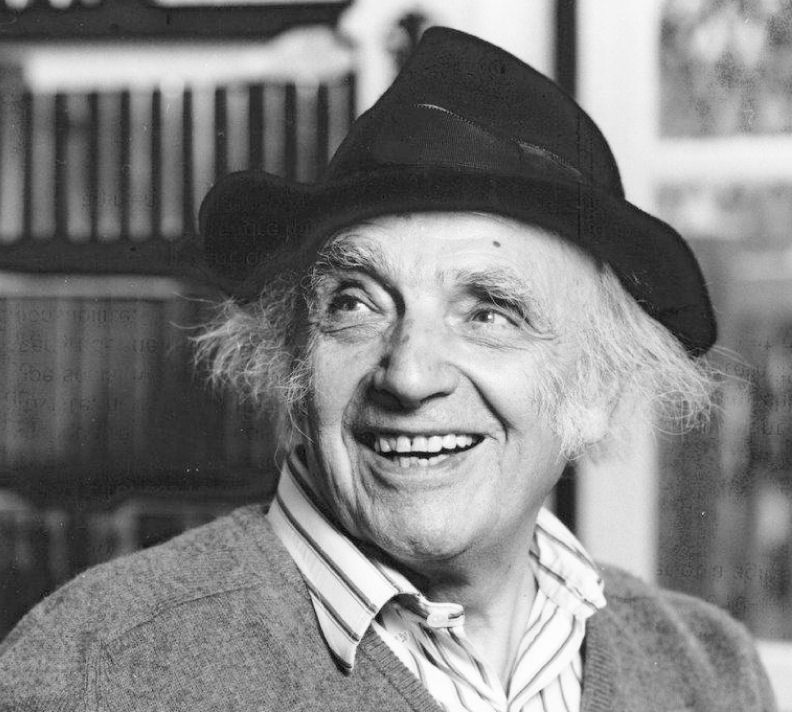

Continuing the author's growing popularity in French university literary circles, two books on Verne's socio-political ideas were published durng the 1960s and 1970s. In 1971, Jean Chesneaux (1922-2007), professor at the Diderot University in Paris and member of the French Communist Party until 1989, published his research about the (sometimes surprising) political and social views of Jules Verne (Figure 49) [73]. His provocative book was made available in English in 1973 [74]. It was translated in German and other languages too. He was following the footsteps of another Verne specialist, Pierre Macherey, who commented on Verne's political opinions and positions from a socio-Marxist perspective in a text published in French in 1966 and translated into English in 1978 [75].

|

|

|

|

| Figure 49. Jean Chesneaux and his two books about the political ideas of Jules Verne (second edition of the first one in 1982, first edition of the second one in 2001, and the English translation, 1972) | |||

A new, important biography (Figure 50) was published in Paris by Hachette in 1973. Jules Verne's grandson, Jean-Jules Verne (1892-1980), wrote a book of 384 pages, full of details and memories about his grandfather [76]. This new family biography succeeded in shining a new light onto Verne's life, replacing the older and unreliable biography by Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe. Jean-Jules Verne's publication was important enough that this biography saw a second, corrected and improved edition in 1978 and was translated into English in 1976 [77]. Charles-Noël Martin was in contact with Jean-Jules Verne and the Municipal Library of Nantes keeps several letters in which Martin comments and critiques this biography. Family memories and comments about the letters between the Hetzels and Verne are the most interesting part of the book. Much less interesting (especially for Vernians) are the lengthy summaries of the novels.

|

|

| Figure 50. Jean Jules-Verne (1892-1980) and the biography of his grandfather | |

After over 30 years of work in the field, Simone Vierne (1932-2016) (Figure 51) pioneered new paths in university Vernian scholarship. In 1973, she published her PhD dissertation—the first in France about Jules Verne—as an 820-page book treating Verne as an initiatory writer [78]. In 1989, Simone Vierne became emeritus professor at the University of Grenoble (France) where she had taught for many years and continued to publish books and numerous articles about Jules Verne. She was also a regular contributor to the Jules Verne Society.

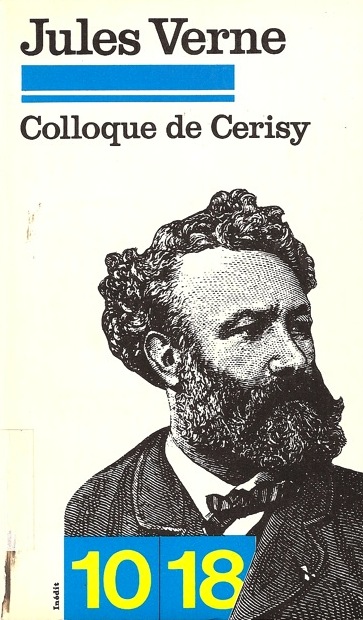

In addition to the meetings of the French Jules Verne Society, Vernian researchers began to gather in other conferences and seminars, the first being held in Nantes in 1975. The second one took place in Amiens in 1977 and Cerisy la Salle hosted the third one in 1978, the year of the huge celebrations of Verne's 150th birthday. Even famed science fiction writer Ray Bradbury crossed the Atlantic to be present at the Cerisy la Salle seminar (Figure 52) [79].

|

|

|

| Figure 51. Simone Vierne (1932-2016) and her PhD thesis Jules Verne and the Initiatory Novel | Figure 52. The Colloque de Cerisy of 1978 | |

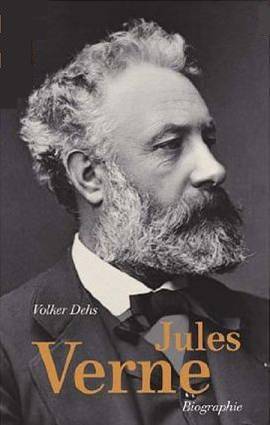

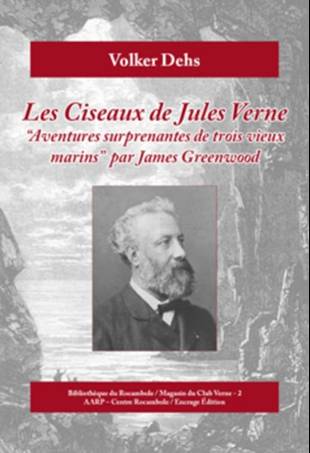

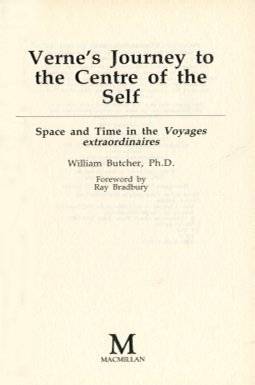

These conferences were the first opportunity for several young promising talents in Verne studies to get together and to create a kind of esprit de corps which has caracterized the Vernian research since then. Some of the presenters and speakers would become the most influential Verne scholars during the 1980s and 1990s, such as Jean-Pierre Picot, Daniel Compère, Simone Vierne, Marie-Hélène Huet, Robert Pourvoyeur, Volker Dehs, François Raymond, William Butcher, and Olivier Dumas. These meetings also helped Jules Verne to eventually become part of the French literature canon, often considered as a closed world by French universities and professors of literature [80].

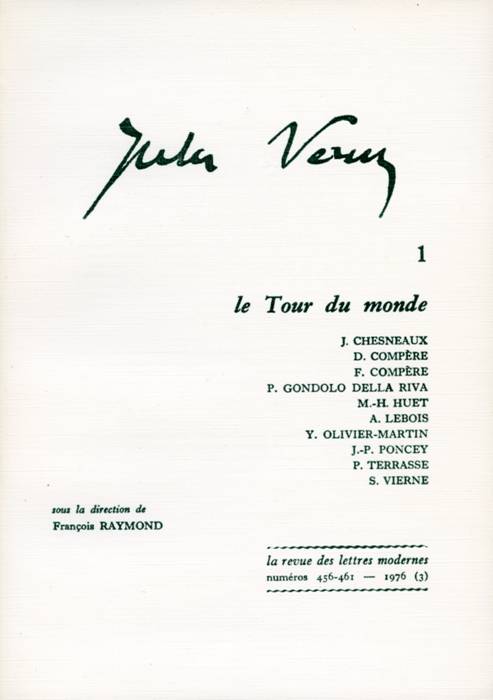

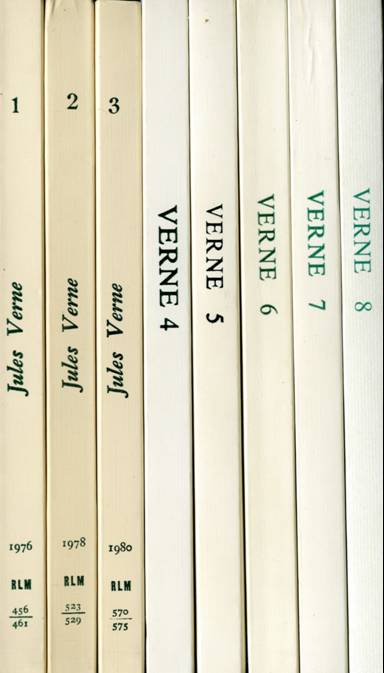

In 1976 began the publication of a collection of important French academic studies about Verne. Under the leadership and inspiration of literary critic François Raymond (1926-1993), who was the Satrape de Vernologie in the Collège de Pataphysique, the Série Jules Verne (Jules Verne Series or Collection) eventually produced eight issues through 2003, with each issue containing 8-10 scholarly articles on a specific Verne-related theme (Figure 53). The goal of the collection, in the mind of François Raymond and his publisher, Minard / Lettres modernes, was to help Jules Verne to join the ranks of the great writers (like Hugo, Zola, Molière, Voltaire, Rousseau, et al.) of the French literary tradition. The first six volumes were organized by François Raymond, the two last by Christian Chelebourg following Raymond's death in 1992.

|

|

|

| Figure 53. François Raymond and the volumes of the Série Jules Verne | ||

The sixth volume opens with a tribute to Raymond by Chelebourg:

En dirigeant cette Série avec une rigueur et une finesse exceptionnelles, M. Raymond en fit, dès le premier numéro, paru en 1976, l'organe où se concentrait le meilleur de la recherche vernienne; et il contribua ainsi, avec efficacité, à l'une des œuvres qui lui tenaient le plus à cœur : la réévaluation littéraire de Jules Verne.

In directing this series with both rigor and exceptional finesse, Mr. Raymond created, from the first issue, published in 1976, a collection where was concentrated the very best Vernian research. In this way he contributed, with great effectiveness, to one of the goals closet to his heart: the literary reassessment of Jules Verne.

The thematic titles of these eight books demonstrate well the different tracks explored by Vernian research: Le Tour du monde (Around the World), L'Ecriture vernienne (Vernian Writing), Machines et imaginaire (Machines and Imagination), Texte, image, spectacle (Text, Image, Spectacle), Emergences du fantastique (Emergences of the Fantastic), La Science en question (A Question of Science), Voir du feu — contribution à l'étude du regard (Looking at Fire—Contribution to the Study of the Gaze), and Humour, ironie, fantaisie (Humor, Irony, Fantasy) [81].

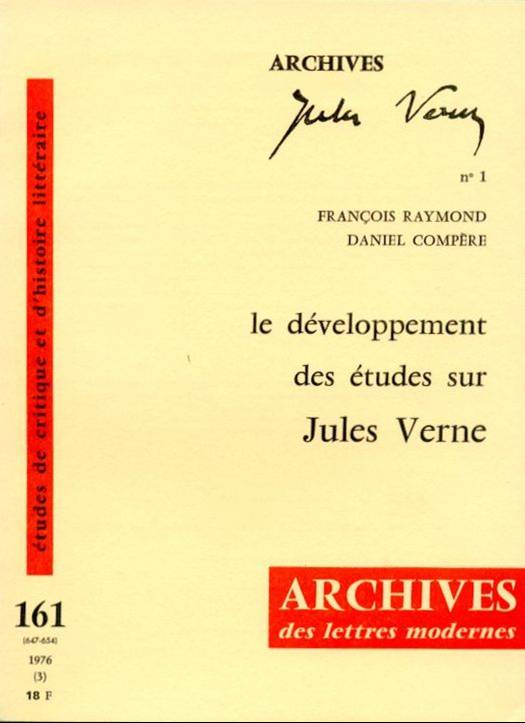

As early as 1976, François Raymond and Daniel Compère identified two basic directions that Vernian research would take in the years to come [82]. In a short overview of French criticism on Verne published by Minard (Figure 54) the authors argue that the first direction would be in the area of « connaissance appliquée, inductive, opératoire » (applied, inductive, operative knowledge), a scholarship path opened by Butor in 1949, Moré in 1960 and 1963, and Vierne in 1973 with her first French PhD thesis about Jules Verne.

|

|

|

| Figure 54. The first book dedicated to Vernian research | Figure 55. Histoires inattendues and Textes oubliés in the 10/18 collection | |

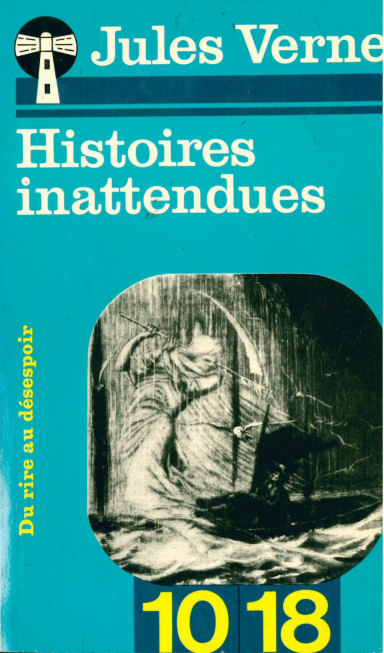

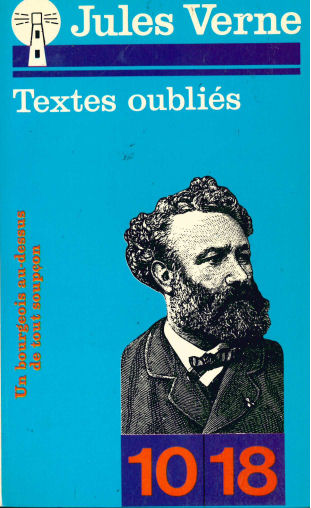

And the second direction would be an expansion of the Verne “inventory,” by publishing everything Verne had written. That path was opened by the Rencontre (Lausanne, Switzerland) collection and by the Union générale d'édition books (Paris, with their 10/18 collection under the lead of Francis Lacassin) where several lesser-known Verne novels, never republished since the nineteenth century, were finally reprinted [83], and where other rare Verne texts were published in two volumes (Figure 55) with the titles of Histoires inattendues (Unexpected Stories) and Textes oubliés (Forgotten Texts).

Although not covered by the Raymond/Compère overview, the world of Anglophone Vernian research during the 1960s and 1970s also began to stir. The main problem for Vernian scholars outside of the French-speaking world is the fact that only his novels (and not all of them) were translated (and sometimes very poorly). This meant that the Anglophone research had to be done based on translations, instead of on the original texts, that only part of Verne's œuvre was available in translated form, and that very little modern French criticism on Verne was available in translation.

Sometimes the translations of the novels were rather good, those done in Portuguese or Russian for example. The most horrific translations were the English ones, done in such a bowdlerized way, so that some of them do not deserve to be called translations at all.

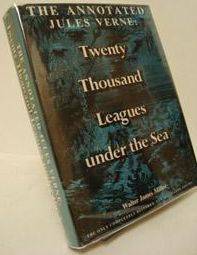

In the 1960s, NYU (New York University) professor Walter James Miller discovered and publicized the poor quality of the Mercier Lewis [84] translation of Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas), which is by far the most popular Verne text in the Anglo-Saxon world. Beginning in 1966, he published several good, complete, and reliable translations of the novel [85]. In 1976, he published the first critical edition of the novel, using and combining the two different published texts in French available to him at the time, the so-called pre-original edition (serialized in the Magasin d'éducation et de recréation, twice a month between March 20, 1869 and June 20, 1870), and the novel in book form by Hetzel (the in-octodecimo edition published by Hetzel on October 18, 1869 for the first volume, and on June 13, 1870 for the second volume and the in-octavo illustrated edition put on the market by Hetzel on November 16, 1871) [86].

In the late 1960s, still in the United States, a small group of Verne aficionados and science fiction fans came together, under the leadership of Ron Miller [87] and Lawrence Knight. They took the name of Dakkar Grotto. Historically, it might be considered as the second American Jules Verne Society, after the one of the 1940s, created by Willis Hurd. What remains of the club today is a fanzine, simply titled Dakkar, with two issues published, a third one planned, but never printed, making a total of 93 pages. The first issue (1967) was filled with essays by Ron Miller and Lawrence Knight, with a last page of text by Thomas Miller. The second issue (1968) carried the names of James Iraldi, Nathan Bengis (both from the previous AJVS), I.O. Evans, and Sam Moskovitz [88]. The third issue (1969) would have carried texts by I.O. Evans and H.J. Hardy.

The End of the 1970s and through the 1980s — New Texts and Facts

The year 1978 was the 150th birthday of Jules Verne. With the publication of many new studies, it was a turning point in the history of Vernian scholarship, and also in the worldwide reception of Verne.

French publishers discovered that they could make money by selling Jules Verne. Following the footsteps of Rencontre and the Livre de poche, several of them offered “complete works of Jules Verne” through monthly subscriptions (for example Michel de l'Ormeraie and Jean de Bonnot in France). In fact most of the readers usually bought only the best known novels which were the first printed in such collections and ignored the rest.

Hundreds of articles and dozens of books were published in 1978 worldwide, which made Verne even more popular. Although very few of them offered new information and new research discoveries (in the way that Moré or Chesneaux had done in the 1960s or early 1970s), they no doubt had a great influence on Verne’s reputation in the French university system. In 1978, for the first time, a novel by Jules Verne—Voyage au centre de la Terre (Journey to the Center of the Earth)—was placed on the French Agrégation reading list, an important recognition of Verne’s literary merit by French academe.

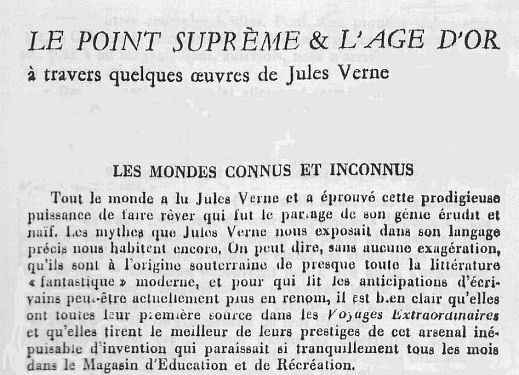

Included among the many books published in 1978 was a Freudian psychoanalytic study of Verne by Marc Soriano (1918-1994), whose analysis of Verne's works tended to “sexualize” them, especially by finding hidden meanings behind the names and word games [89]. Two other major Verne studies published in France in 1978 included the University of Nantes professor Christian Robin’s excellent Un Monde connu et inconnu [90] and Charles-Noël Martin’s previously mentioned La Vie et l’œuvre de Jules Verne.

In English-language Vernian research, the year 1978 saw the publication of Peter Costello’s fine study (despite its title) Jules Verne: Inventor of Science Fiction, Peter Haining’s very useful The Jules Verne Companion, and Walter James Miller’s second updated Verne translation, The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon [91].

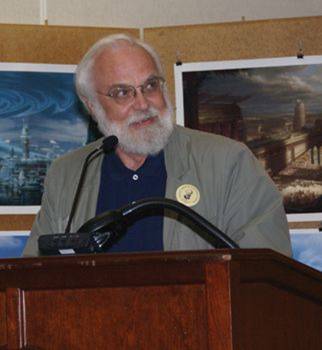

During the 1980s, several new and important contributions to Vernian research appeared in both French and English. The theme of machinery and machines in Verne’s novels, long considered an integral part of his general mythology, became the subject of detailed narratological analysis in 1982 by Jacques Noiray, who studied the role played by machines in the literary structure of the works of several French novelists during the second half of the nineteenth century [92]. In French academe, two PhD dissertations focusing on Verne were completed by Charles-Noël Martin [93] and Jean Delabroy [94]. And, a series of three international literary conferences on Verne were organized in Amiens, whose published proceedings featured many cutting-edge articles by Vernian scholars such as Jean Bessière, Simone Vierne, Robert Pourvoyeur, Olivier Dumas, Daniel Compère, Jean Chesneaux, Arthur Evans, William Butcher, Alain Buisine, and Christian Chelebourg [95].

Although during the 1980s, in addition to the ongoing publication of the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, four other noteworthy events occurred in France, pushing Vernian research to a higher level. In 1981, the Municipal Library of Nantes bought Verne's manuscipts from the Verne family, two new magazines were launched, two unknown plays were discovered, and some surprising breakthroughs were made concerning the sometimes huge differences in the texts of the Verne novels published after his death in 1905.

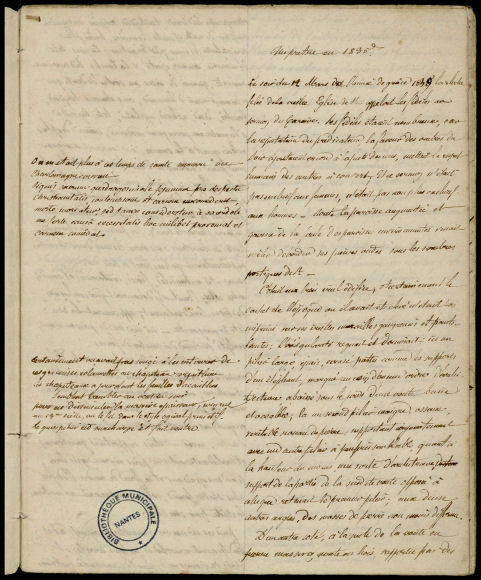

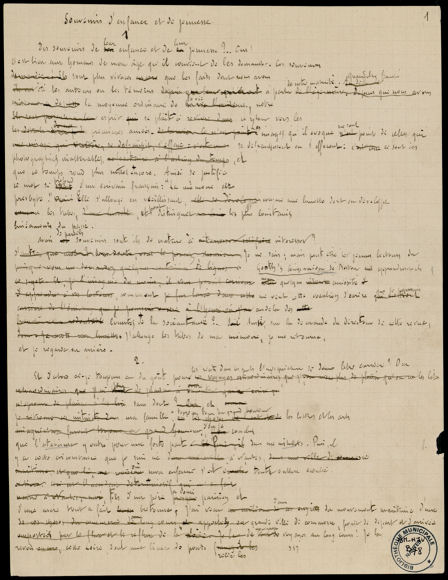

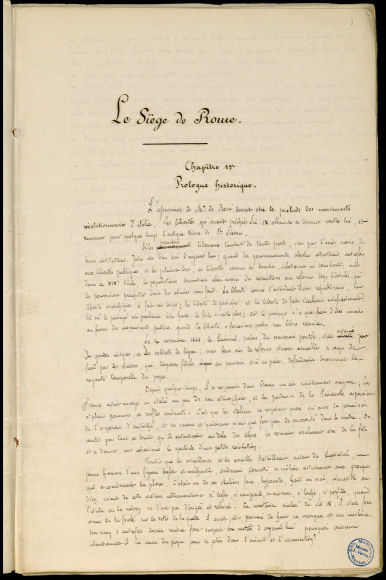

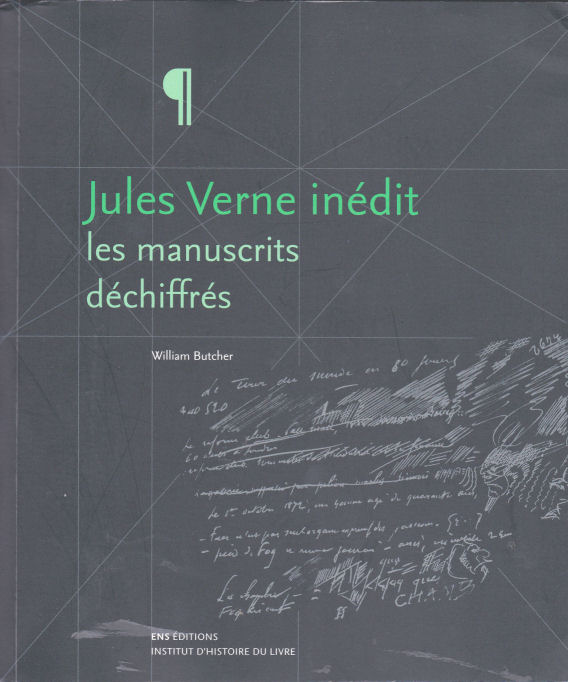

In 1981, the Municipality of Nantes acquired the Jules Verne manuscripts from Verne's family. Before a public auction could take place, the French government decided that his manuscripts should remain in France and they are now kept in Nantes. For the first time, a majority of Verne's hand-written rough draft of his novels, plays, and short stories were made available to scholars for consultation, and they are now available online since the mid-2000s (Figure 56) [96].

|

|

|

| Figure 56. Three first pages of Jules Verne manuscripts available online on the site of the Bibliothèque municipale de Nantes: Un Prêtre en 1835, Souvenirs d'enfance et de jeunesse, Le Siège de Rome | ||

Much of the research during the 1980s questioned and discussed many of the assumed “facts” about Verne's life and works which were previously regarded as true. Jules Verne was now viewed as a dynamic writer, passionate about politics and sociology, freedom-loving and rarely taking himself seriously, playing on words and filling his novels, plays, and stories with tongue-in-cheek asides and authorial winks so well hidden that, for a long time, his wholesome, grandfatherly public image was not affected.

During this decade, two new magazines began to be published in France. In 1981, the first issue of the Cahiers du Centre d'études verniennes et du Musée Jules Verne (Notebooks of the Center of Vernian Studies and the Jules Verne Museum) came out in Nantes (Figure 57), with a total of thirteen issues until 1996, when they became part of the Revue Jules Verne (Jules Verne Review).

Figure 57. Cover of the Cahiers of Nantes

In Amiens, for eleven years, from 1985 to 1995, the Centre de documentation (Documenation Center) published thirty-six issues of a newsletter, with a very simple title: J.V. In a similar way as did the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, the J.V. of Amiens (Figure 58) as well as the Cahiers of Nantes have published many articles by scholars, researchers and academic specialists, not only from France, but also from other countries.

|

|

|

| Figure 58. Three covers of the J.V. of Amiens | ||

To sum up, in the 1980s, there were four venues for publication about Jules Verne available in France: the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, the J.V. in Amiens, the Cahiers in Nantes, and the volumes published by Minard in the collection Série Jules Verne. Still today, these four publications remain an indispensable source of information for researchers and scholars.

In terms of primary materials, the letters between Hetzel and Verne at the National Library in Paris had not yet been published and were still available only on site. Only obscure texts (some not even known by scholars) had been republished in collections like Rencontre, 10/18 or in the four French magazines. A few lesser-known stories had been translated into English before the 1980s, like “Fritt-Flacc,” “Story of my Boyhood,” “Gil Braltar,” and “A Voyage in a Balloon” [97].

Two plays were discovered in 1979 in the Archives of the Censorship Office of the Third French Republic. In the 1870s Emperor Louis-Napoléon created the Censorship Office which functioned until 1906. Every play had to go through the Censorship Office before being allowed to be performed on stage. These two plays had to follow the same procedures and were copied by hand by an employee of the Office. They were performed on stage, and the newspapers of the time reported about them.

So, Verne scholars knew about the plays (through the reviews), but the common opinion was that the text of them was lost. When the Vernian community learned about their discovery, the excitment was such that every specialist of Verne wanted these texts to be published as quickly as possible.

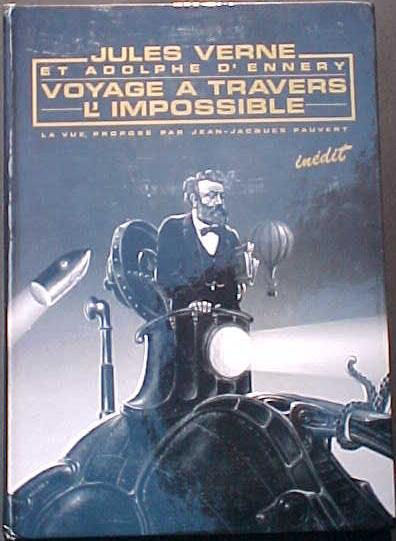

Voyage à travers l'impossible (Voyage Through the Impossible) and Monsieur de Chimpanzé (Mister Chimpanzee) were made available to the public in 1981 [98]. The discovery of these two unknown texts (Figure 59) marked the beginning of a great many other unexpected finds, something that still continues today.

|

|

|

| Figure 59. Cover of the two editions of Voyage à travers l'impossible and of Monsieur de Chimpanzé | ||

For example, another discovery was made during the same time period, but pertaining to Verne's life. The only knowledge scholars had about Verne's life was related by Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe in her biography of 1928 and by Jean-Jules Verne's more accurate but still spotty biography of 1973 and 1978. And an important missing part was the relationship between Jules Verne and his son Michel.

Suspicion of a possible collaboration between father and son in the composition of Jules Verne's later works became a growing topic of discussion among the Vernian specialists. In 1978, Piero Gondolo della Riva convincingly demonstrated not only that such a collaboration existed, but also that all of Verne's posthumous novels published by Hetzel and Hachette from late 1905 to 1919 had been completely or partially rewritten by his son Michel [99]. This revelation was like an earthquake that shook the Vernian world. The discovery of the manuscripts written by Jules Verne himself allowed researchers to compare the original texts and the 1905-1919 publications. As a result, the Société Jules Verne immediately began to publish Verne's manuscripts of the five posthumous novels that were modified by Michel (Figure 60 and 61) [100].

|

|

| Figure 60. Piero Gondolo della Riva and one of the original posthumous works by Jules Verne, edited by the Société Jules Verne | |

It was also found that two other novels, L'Agence Thompson and Co. (The Agency Thompson and Company) and L'Etonnante aventure de la Mission Barsac (The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission) were totally written by Michel and published under his father's name. Michel was a good writer too and wrote several pieces published under his name. The controversy is still going on among the Verne scholars to know if the modifications made by Michel were improvements or mutilations of his father's texts. Each reader must decide. As example, the character of Zéphyrin Xirdal was added by Michel in La Chasse au météore (The Meteor Hunt).

|

|

| Figure 61. Two of the original posthumous works by Jules Verne, edited by Stanké in Montréal and L'Archipel in Paris | |

Recently, the English translation of the original manuscripts of these posthumous novels were made available to English-speaking readers [101].

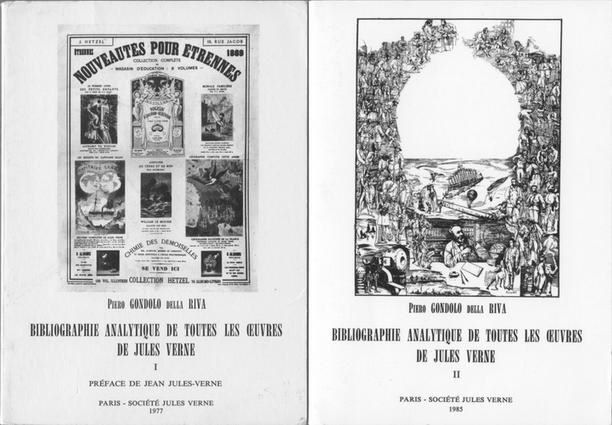

At the end of the 1970s and thoughout the 1980s, it became obvious that more bibliographic tools on Verne and his Voyages extraordinaires would be very useful to scholars and researchers. No complete bibliography existed of Verne's primary works or of the growing secondary literature about them. At the end of the 1980s, three bibliographies (Figure 62) appeared that helped to boost Vernian studies worldwide [102]. Two were in French by Piero Gondolo della Riva and Jean-Michel Margot, and one was in English by the American bibliographic team of Edward Gallagher, Judith Mistichelli, and John Van Eerde.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 62. The three bibliographies about Jules Verne available during the 1980s | |

With Verne now being recognized as a true literary writer, book collectors were more and more interested in the beautiful and shiny Hetzel bindings (« cartonnages »). Even if collecting the Hetzel bindings is not really part of the “Vernian studies”, it can be considered as a viable research area, due to the fact that over more than 100 years, from 1863 until today, the Verne editions are tracked and studied. Two main bibliographies by André Bottin and Philippe Jauzac have attempted to catalog all the variations of the bindings [103].

Approaching the End of the Twentieth Century — Deepening Vernian Research

In the history of spreading knowledge, humanity has passed through three main phases. The first was to use handwriting to transmit information, the second involved printing it in books, today knowledge is digital and, with the Internet, we are disseminating information at the speed of light. That's why you are able to read what you are reading now./p>

In the 1990s, globalization began and slowly the way in which Verne and his works were researched had to change too. In addition, the end of the century and the approaching millenium was also a time of consolidating the discoveries and the new ways of looking at Verne's works that had been developed during the past few decades.

In France, in 1996 began a period of transition which gradually replaced the Compère family with younger and less experienced people to lead the Jules Verne Documentation Center in Amiens. By 1996, the Center replaced the publication J.V. whose look was obsolete and replaced it with Revue Jules Verne (Jules Verne Review) with its 38th issue published in 2015 (Figure 63).

|

|

|

| Figure 63. The Revue Jules Verne published by the Jules Verne Center in Amiens | ||

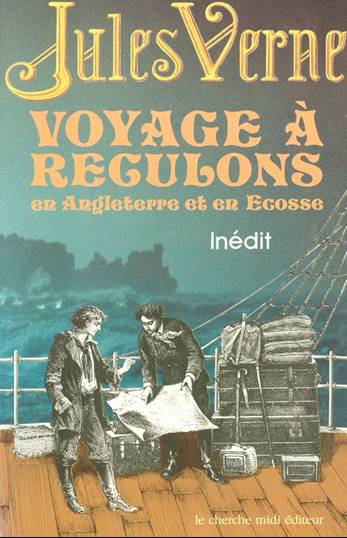

Two “new” Verne publications (Figure 64) appeared in 1989 with Voyage en Angleterre et en Ecosse (Travel to England and Scotland) [104], followed the same year by Poésies inédites (Unpublished Poems) [105].

|

|

| Figure 64. The Verne's Travel to England and Scotland and the Poems | |

The same Parisian publisher also added three other “new” volumes [106] in 1991, 1992 and 1993, to have his Bibliothèque Verne (Verne Library) complete. All the volumes have notes and comments by Christian Robin. A sixth volume was added in 2005, presenting the unpublished plays and introduced also by Christian Robin [107] (Figure 65).

Like all the previous volumes, using the Nantes manuscripts, this book on Verne's theater presented for the first time more than a dozen plays, with titles like La Conspiration des poudres (The Gunpowder Plot/Conspiracy), or Les Heureux du jour (Happy for One Day).

|

|

|

|

| Figure 65. Covers of Uncle Robinson, A Priest in 1839, San Carlos, and the Unpublished Plays | |||

Fourteen years earlier, in 1991, the Municipal Library of Nantes published three volumes containing the transcript of the unpublished manuscripts. Done quickly, these three volumes (Figure 66) were printed with 30 copies each, to ensure the copyright rights of the City of Nantes on the unpublished Vernian texts [108].

|

|

|

| Figure 66. The three volumes of the Manuscrits nantais | ||

In 1994, the discovery of the manuscript of Paris au XXe siècle (Paris in the 20th century) drew a great deal of media attention of Verne's œuvre (Figure 67), and the manuscript was acquired by the City of Nantes in 2000 [109].

|

|

| Figure 67. Paris au XXe siècle and Paris in the Twentieth Century | |

At the same time, it became obvious that the letters between Hetzel and Verne available for research in the National Library of France in Paris should be published with notes and comments.

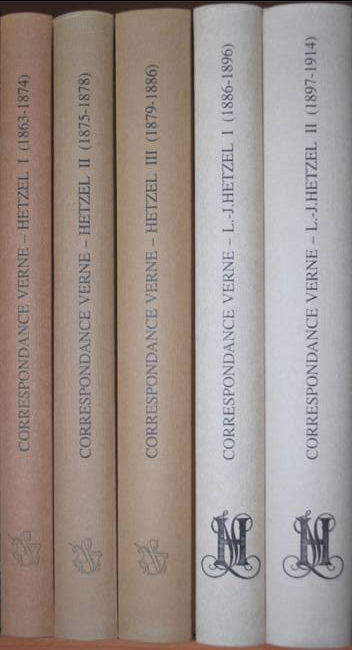

The correspondence between the Hetzels (father and son) and the Vernes (father and son), which had been hibernating at the National Library of France in Paris since 1965, soon became available to scholars and the general public. As mentioned previously, between 1999 and 2006, the Swiss publisher Slatkine printed five volumes edited by Olivier Dumas, Piero Gondolo della Riva, and Volker Dehs (Figure 68), which contained more than 700 letters, a huge gift to Vernian researchers [110].

|

|

|

| Figure 68. The five volumes of letters between the Hetzels (father and son) and the Vernes (father and son) | ||

Jules Verne didn't write only to his publishers, but also to his family and his friends. There are thousands of letters as yet undiscovered and unpublished. Verne's correspondence remains far from being identified and organized in any systematic way. Some letters to friends or family members remain inaccessible in private collections. Auctions are relatively rare, and online auction sites offer in most cases only short answers sent by Verne to his readers worldwide. Very courteous, Verne answered all letters he received with such short thank you notes, and they cannot all be listed. There are just too many and they are without interest for Vernian research. The biggest part of his non-editorial correspondence has been published already in 1936 by Turiello and in 1938 by Guermonprez in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne. Slowly some other letters were published until 1988, when Olivier Dumas published his Verne biography with 191 letters by Verne to his family [111]. Even today, new Verne correspondence is published when a discovery is made and it is deemed worthy of publication. The most accurate list of Verne's published letters can be found in Dehs's Bibliographic Guide, discontinued in 2002 [112].

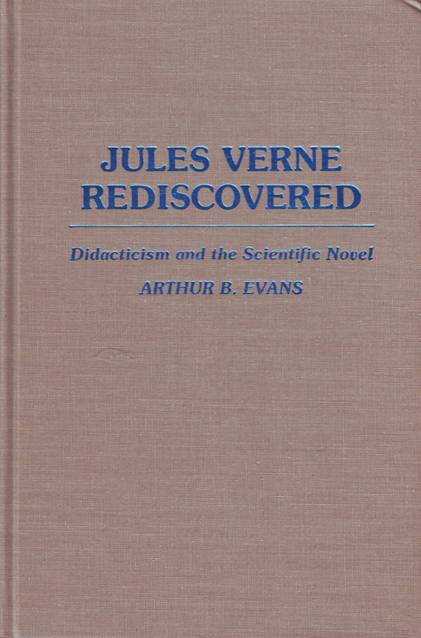

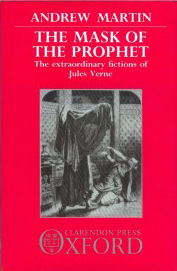

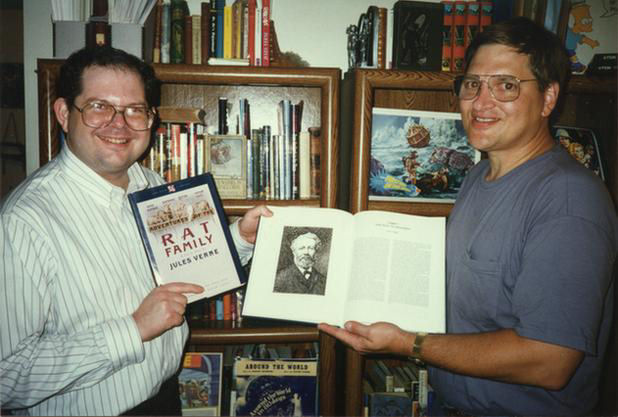

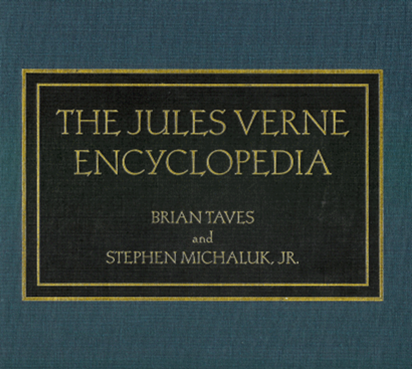

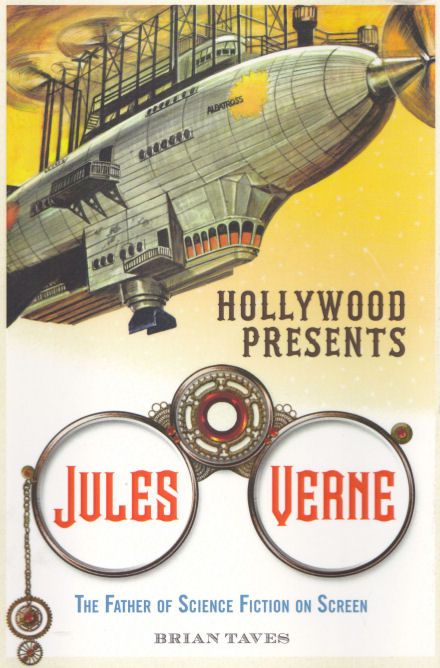

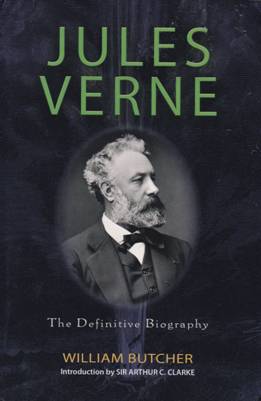

During the end of the late 1980s and the early 1990s, the “old guard” of Vernian scholars was slowly replaced by newer and younger researchers. Several monographs were published, some as result of PhD dissertations. All of these scholars became members of the Société Jules Verne in France or the North American Jules Verne Society, founded in 1994. Daniel Compère in France, Volker Dehs in Germany, Robert Pourvoyeur in Belgium, Piero Gondolo della Riva in Italy, Andrew Martin in the U.K., William Butcher in the U.K. (later in Hong Kong), Arthur B. Evans, Brian Taves and Walter James Miller in the United States filled the final decade of the century with their writings, bringing a “truer” Jules Verne to a wider audience.

Following the path opened decades before by Butor and Moré, they offered deeper and more exegetical studies of Verne's œuvre. After decades of looking at Verne's works (mainly the novels) biographically and thematically, it was time to study the way he wrote, analyzing his sources, the narrative structure of his writings, connecting them together, and studying his writing style.

Walking in the footsteps of the psychiatrist Lacan [113], and the literary theorists Genette [114] and Barthes [115], several younger Vernian scholars and researchers published books and articles on Verne, which applied their ideas in critical theory, literary theory and structuralism.In France, Daniel Compère published two books showing Verne's literary credentials and analyzing his works within a literary perspective [116]. Compère argued that the creative originality of Jules Verne is visible in the way he stands out from his rewritten or assimilated models, extending even up to parody and reaching the metatextual level (Figure 69).

|

|

| Figure 69. The two Compère books, being a good introduction to Verne, the writer | |

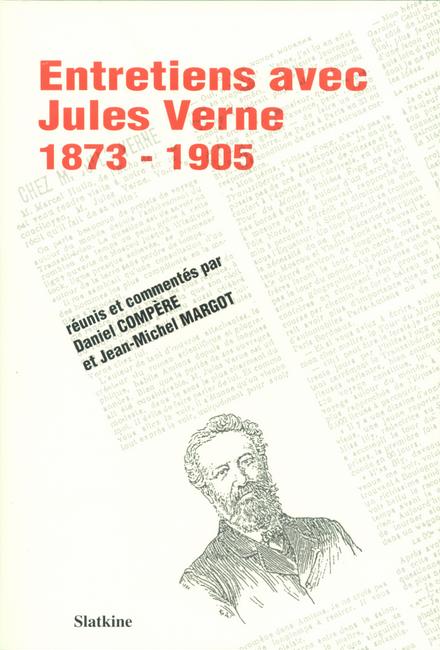

Besides his letters and speeches, there is another way to get (almost) the first words from Jules Verne about his life and writings. Several journalists and celebrities visited him in his home in Amiens and published their interviews. The first collection of Verne interviews, edited by Daniel Compère and Jean-Michel Margot, was published in 1998, covering the time period between 1873 and 1905 with 32 interviews of Jules and 2 of Michel (Figure 70) [117].

Figure 70. Cover of the first book with Verne's interviews

Reading Verne from a psychoanalytic perspective, Christian Chelebourg published in 1999 a very thorough reflection on the Vernian corpus distinguishing between two fundamental fantasies that determined and marked Verne's imaginary world: the visual linked to the emancipation from a too powerful father and the domestication of the orality connected to the image of the mother [118].

Applying the structuralist methodology to the Voyages extraordinaires (Extraordinary Voyages) since the 1970s, in 2002 Michel Serres [119] offered a new vision and explanation of geometrical patterns, mythical and mythological themes, games, transfer of energies, utopias, and starvation themes in Verne's works.

A professor at the University of Montpellier, Jean-Pierre Picot (born in 1946) became a Verne scholar and specialist without publishing a book about Jules Verne until the end of the century. Instead, he wrote dozens of articles in collected essays about Verne or connected subjects. Minutes or reviews of workshops, colloquia, and meetings also document Picot's presentations. Writing on many varied subjects, such as vehicles, volcanoes, vampires, islands, regression (and more) in Verne's works, Picot concentrated his studies mainly on the themes of tombs and death, the fantastic, the unspeakable, the invisible, and the immeasurable in Verne's works. The list of his publications is available in Dehs's Bibliographic Guide [120].

In the 1990s, a group based at the University of Besançon, published a few books and articles about Jules Verne, without any connexion to other Vernian entities, like the Société Jules Verne, the Documentation Center in Amiens or the Municipal Library in Nantes. Under the leadership of Florent Montaclair and Yves Gilli, at least two book titles by them from 1998 and 1999 deserve to be mentioned [121].

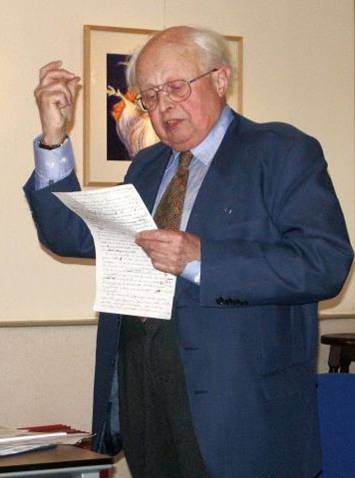

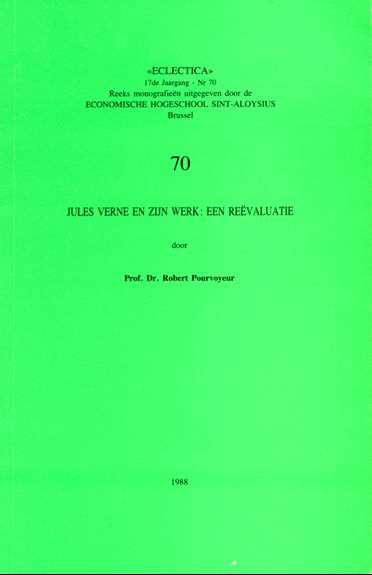

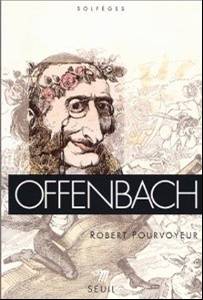

In Belgium, for decades, the Verne scholar was Robert Pourvoyeur (1924-2007). From his first article about Verne published in 1955 [122], he never stopped studying Jules Verne. Recognized worldwide as a specialist of Jacques Offenbach, he became the specialist of Verne the playwright, publishing dozens of articles in specialized journals about Verne's relationships with Hignard and Offenbach, and about operettas and zarzuelas [123]. Speaking fluently in a dozen of languages, professor at the University of Antwerpen, Pourvoyeur (Figure 71) was also the director of information and documentation of the European Communities in Brussels. In 1988 he published the best Verne biography available in Dutch, and in 1994 a biography in French of Jacques Offenbach [124].

|

|

|

| Figure 71. Robert Pourvoyeur (Dutch JV Society archives) and his two main books about Verne and Offenbach | ||

In Italy, following the lead of earlier Vernians such as Mario Turiello, Edmondo Marcucci, and Fernando Ricca, Piero Gondolo della Riva (born in 1948), was able not only to gather the most important and prestigious collection of Jules Verne's works and memorabilia, but also, using his collection as a source of information, to become a specialist and scholar of Verne's life and writings (Figure 60). Publishing many articles, especially in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne and Europe, he was able to add significantly to our understanding of Verne. In 2000 his collection was sold to Amiens Métropole (the French area of which Amiens is the center) and is managed by the Bibliothèque municipale d'Amiens (Public Library of Amiens).

Other collectors, like Philippe Burgaud (Figure 72) in France or Eric Weissenberg (Figure 73) in Switzerland, also used their collections to publish articles about the French publisher Hachette, movies inspired by Verne, and the Hetzel bindings, the so-called « cartonnages » [125], [126].

|

|

| Figure 72. Philippe Burgaud (born in 1942) | Figure 73. Eric Weissenberg (1945-2012) |

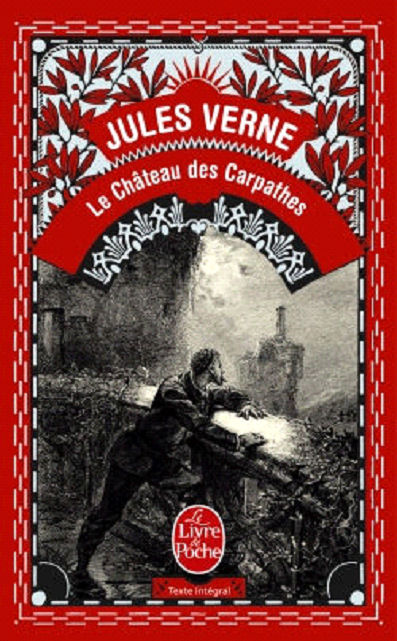

In Romania, two literary critics became specialists of Verne. Ion Hobana (1931-2011) was a leader of the Writer's Society of Romania (Figure 74). Besides Verne, his interests were science fiction and ufology. He wrote several books about Verne, and, being in Romania, did some concentrated research on Le Château des Carpathes (The Castle in the Carpathians), searching for the real castle through several articles published between 1978 and 1990 [127].

Lucian Boia (born in 1944) is a professor at the University of Bucarest, and a specialist in the history of myths and fantasies in the Western world (Figure 75). Fluent in French, he wrote several articles about Verne in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne and published a book in 2005 [128].

|

|

| Figure 74. Ion Hobana | Figure 75. Lucian Boia |