In my 2005 “Bibliography of Jules Verne's English Translations” [1], I examined what was at the time the only available English translation of Verne's 1892 novel Le Château des Carpathes [2]. It was called The Castle of the Carpathians [3] and I gave it a white check mark, indicating that it was of “relatively good quality.” This same nineteenth-century Sampson Low translation later reappeared in the “Fitzroy Edition” as Carpathian Castle [4], edited by I.O. Evans, who made some updates to its style, fixed some of its errors, and abridged it to fit the length requirements of the books in that series.

|

|

|

In 2010, a new English translation of this novel was published in the United States. It featured a revised title, The Castle in Transylvania [5] and included an unusual subtitle at the bottom of the front cover, which said: “Back from the dead: The original zombie story.” The rear cover went on to elaborate:

Before there was Dracula, there was The Castle in Transylvania. In its first new translation in over 100 years, this is the first book to set a gothic horror story, featuring people who may or may not be dead, in Transylvania.

|

|

As a long-time Vernian, I must confess that I was very skeptical about this new translation that was apparently trying to turn Verne's novel into an early horror tale. But I was wrong. Despite its publisher's obvious attempt to find a market for this new book by associating it with today's fads of vampire and zombie fiction, Mandell's translation is exceptionally good. In fact, I would rank it as the best English-language version of Verne's novel produced so far.

But allow me to give you the details of what I discovered when analyzing these three different English translations. In addition to looking at each book's “macro” structure— its title, number of chapters, author footnotes, illustrations, etc.—I did a line-by-line “micro” comparison of the translated text by examining several chapters from the beginning, middle, and end of each edition. In all cases, I evaluated each translation according to three basic criteria: completeness, accuracy, and style.

On the “macro” level, the title of the Mandell translation is obviously the worst, and the Sampson Low title remains the most faithful. All three translations include all of Verne's eighteen chapters, and (thankfully) none has changed the names of the fictional characters or added/deleted any episodes in the story. The Sampson Low is also the only English translation that reproduces—at least some of—the many illustrations by Léon Benett that graced the pages of the original Hetzel red and gold in-octavo editions. And, although none of the three reproduces all of Verne's footnotes, the Mandell translation does include the most substantial of them, as seen here: (SL = Sampson Low, IO = I.O. Evans, M = Mandell)

Puis, aux derniers plans, c'est un admirable chevauchement de croupes, boisées à leur base, verdoyantes à leurs flancs, arides à leurs cimes, que dominent les sommets abrupts du Retyezat et du Paring.1

1 Le Retyezat s'élève à une hauteur de 2496 mètres, et le Paring à une hauteur de 2414 mètres au-dessus du niveau de la mer. (II, 22)

(SL) In the distance lay an admirable series of ridges, wooded to their bases, green on their flanks, barren on their summits, commanded by the rugged peaks of Retyezat and Paring. (II, 20)

(IO) In the distance an admirable series of ridges, wooded at their bases, green on their flanks, barren on their summits, were dominated by the rugged peaks of Retyezat and Paring. (II, 22)

(M) Then, in the far distance, there is an admirable thrust fault of mountains, wooded at their bases, lush with greenery at their sides, arid at their summits, dominated by the sharp summits of the Retyezat and Paring mountains.1

1 The Retyezat rises up to a height of 8189 feet, and the Paring to a height of 7920 feet above sea level. (II, 23-24)

Notice also how Mandell has converted the mountain heights to feet in order to conform with the Anglo-centric references in an English translation.

After examining all three translations in terms of their completeness, I found that the Mandell definitely edges out the other two in overall quality. Here are a couple of examples. In the first one, the shepherd Frik is described as being highly appreciated by his employer, Koltz, because of his skills at shearing and especially his knowledge about animal illnesses, which Verne dutifully enumerates. These diseases are only partially listed in the Sampson Low version (and which are also described as “cattle ailments” even though Frik deals only with sheep); they are chopped out entirely in the IO Evans; and they are included in their entirety (and maybe even one extra!) in the Mandell translation:

Ce troupeau appartenait au juge de Werst, le biró Koltz, lequel payait à la commune un gros droit de brébiage, et qui appréciait fort son pâtour Frik, le sachant très habile à la tonte et très entendu au traitement des maladies, muguet, affilée, avertin, douve, encaussement, falère, clavelée, piétin, rabuze et autres affections d'origine pécuaire. (I, 9)

(SL) The flock belonged to the judge of Werst, the biro Koltz, who paid the commune a large sum for pasturage, and who thought a good deal of his shepherd Frik, knowing him to be a skilful shearer and well acquainted with the treatment of such maladies as thrush, giddiness, fluke, rot, foot rot, and other cattle ailments. (I, 7)

(IO) The flock belonged to the judge of Werst, the biro Koltz, who paid the commune a large sum for pasturage, and who thought kindly of his shepherd Frik, knowing him to be skilful at shearing and experienced with the treatment of such maladies as the animals are prone to. (I, 10-11)

(M) This herd belonged to the judge of Werst, Biró Koltz, who paid the district a large pasturage fee, and who had great appreciation for his shepherd Frik, knowing him to be very good at shearing and very knowledgeable about the treatment of illnesses: thrush, bluetongue, turnsick, vertigo, liver fluke, waterbelly, pink eye, sheep-pox, foot and mouth disease, scrapie, and other diseases of animal origin. (I, 11)

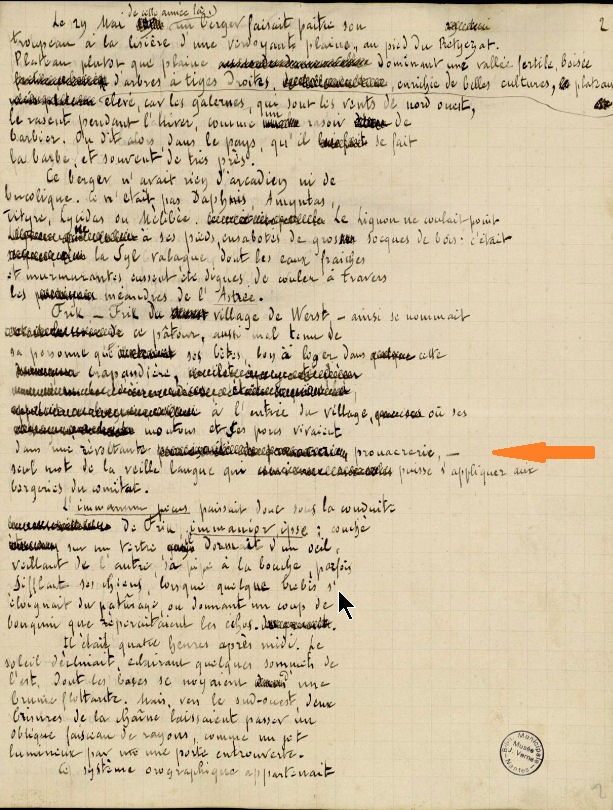

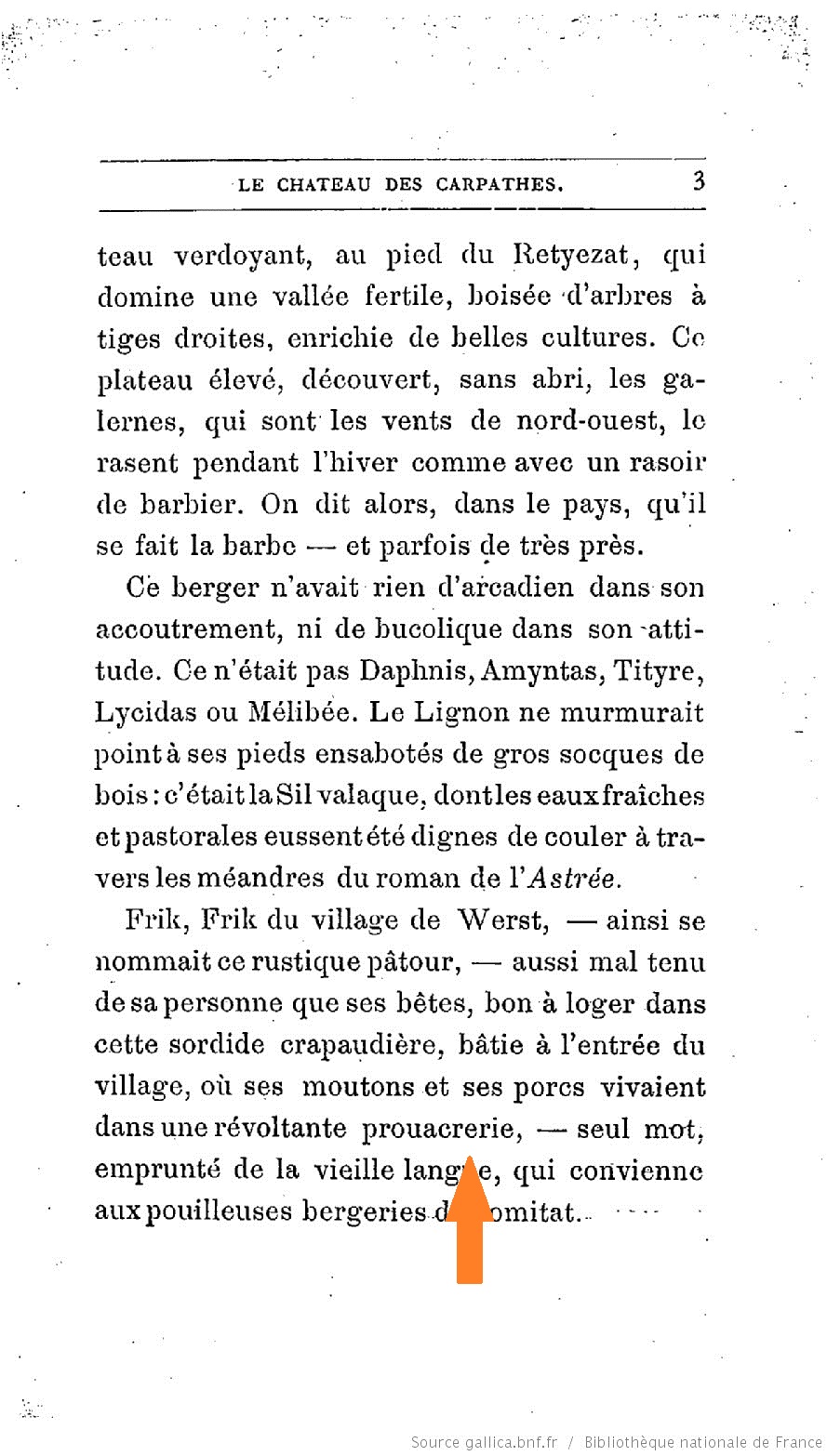

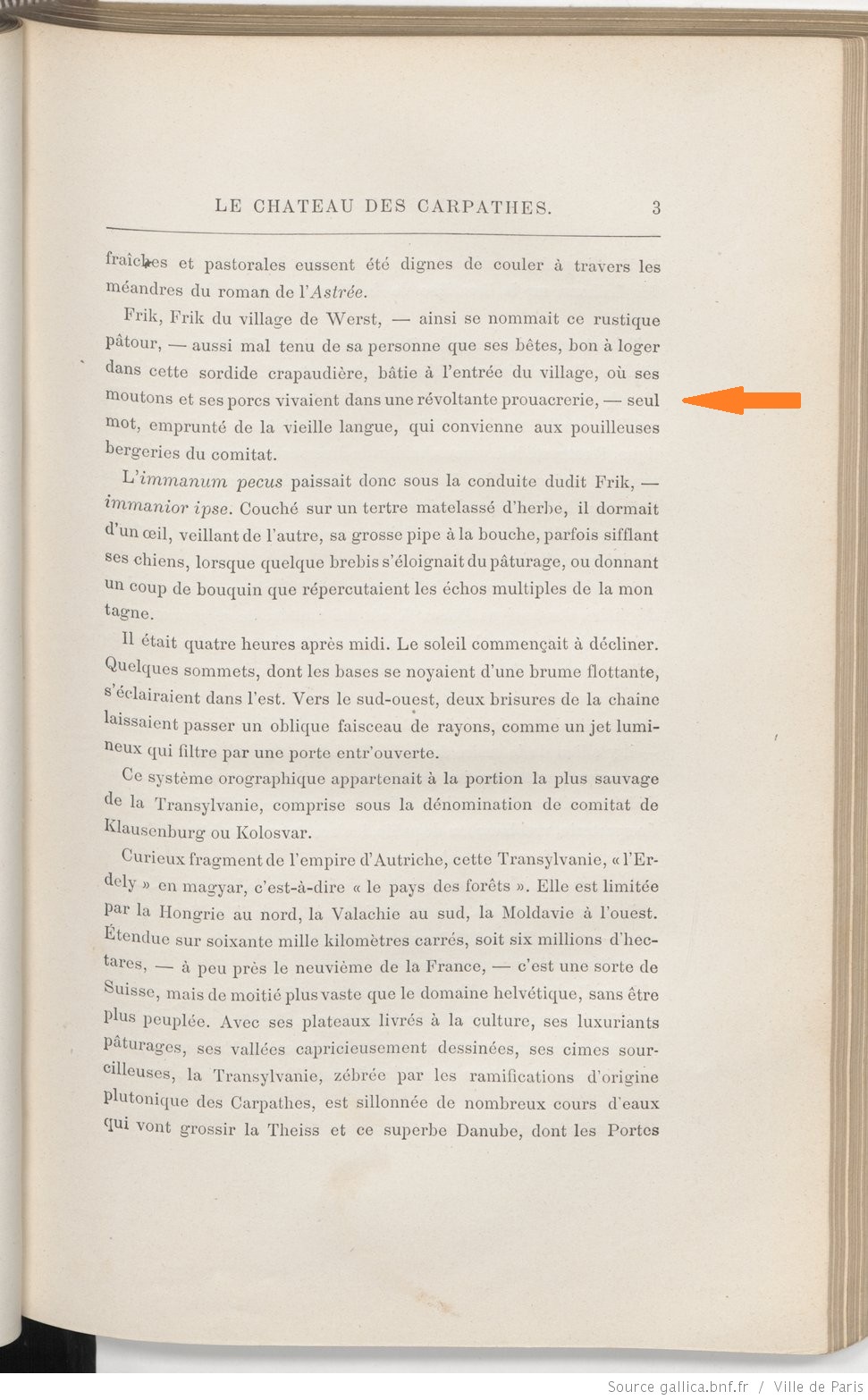

In the next example, the Sampson Low translation simply omits the latter part of Verne's sentence describing the nastiness of a sheep and pig enclosure. The I. O. Evans version attempts to render it (without using an “old word,” as in Verne's original). The Mandell version, however, not only includes the entire phrase but also invents an old-sounding term to duplicate Verne's “prouacrerie” (a misspelling of the antique French term “pouacrerie”— a noun that means extreme dirtiness or filth [“pouah!” = yuck!]) [6]. In so doing, Mandell scores extra points for completeness as well as for trying to reproduce Verne's style:

Frik, Frik du village de Werst — ainsi se nommait ce rustique pâtour — aussi mal tenu de sa personne que ses bêtes, bon à loger dans cette sordide crapaudière, bâtie à l'entrée du village, où ses moutons et ses porcs vivaient dans une révolante prouacrerie [sic] — seul mot, emprunté de la vieille langue, qui convienne aux pouilleuses bergeries du comitat. (I, 3)

(SL) Frik, Frik of the village of Werst—such was the name of this rustic shepherd—was as roughly clothed as his sheep, but quite well enough for the hole, at the entrance of the village, where sheep and pigs lived in a state of revolting filth. (I, 2)

(IO) Frik, Frik of Werst village—such was the name of this rustic shepherd—was as roughly clothed as his sheep, but quite well enough for the sordid hole built at the entrance of the village, where his sheep and pigs lived in a state of revolting filth,—the only word, borrowed from the old language, fit to describe the lousy sheepfolds of the land. (I, 7)

(M) Frik, Frik from the village of Werst—this rustic shepherd was named—as unkempt in his person as his animals, as he should be from living in that sordid hovel erected at the entrance to the village where his sheep and pigs lived in a revolting “verminary”—the only word, borrowed from the old language, fitting for the squalid sheepfolds of the district. (I, 6-7)

In terms of overall linguistic accuracy, the Mandell version consistently ranks higher that the others. Here are a few examples. In the first, the word “sablier” (hourglass) is mangled by the other translators:

On dirait qu'ils sont les commis voyageurs de la Maison Saturne et Cie, à l'enseigne du Sablier d'or. (I, 12)

(SL) They are commercial travellers for the house of Saturn and Co. of the sign of the Golden Shoe. (I, 10)

(IO) They are, so to speak, commercial travellers for the sky. (I, 13)

(M) You could say they are the traveling salesmen of Saturn and Co. under the sign of the Golden Hourglass. (I, 14)

In the next example, the Sampson Low translator and I. O. Evans both misread the second set of numbers listed in Verne's text; the first are clearly in feet, but the second are in the old French unit of “toises” (where 1 toise = approx. 6 ft.). Mandell picks up on this difference of measurement and converts the numbers correctly:

A huit ou neuf cents pieds en arrière du col de Vulkan, une enceinte, couleur de grès, lambrissée d'un fouillis de plantes lapidaires, et qui s'arrondit sur une périphérie de quatre à cinq cents toises, en épousant les dénivellations du plateau... (II, 20-21)

(SL) Some 800 or 900 feet in the rear of Vulkan Hill lay a grey enclosure, covered with a mass of wall plants, and extending for from 400 to 500 feet along the irregularities of the plateau... (II, 19)

(IO) Some hundreds of feet to the rear of Vulkan Hill lay a grey enclosure, covered with climbing plants and extending for several hundred feet along the irregularities of the plateau... (II, 21)

(M) Set back 800 or 900 feet from the Vulkan Pass, a battlement, the color of sandstone, cover with a jumble of lapidary plant, extending to a periphery of about 2,500 to 3,000 feet around, conforming to the uneveness of the plateau... (II, 22)

And, in the following example, one translation error in chapter 2 seems to have generated another error in chapter 6. The Sampson Low translator evidently misread Verne's “mardi” (Tuesday) for “jeudi” (Thursday) and then later felt obliged—for consistency's sake—to alter Verne's text from Tuesday to Thursday. I. O. Evans caught this mistake and corrected it in his edited version of the Sampson Low translation, although he dropped Verne's [mis?]use of the term “babe.” In contrast, Mandell not only got the days right but also kept Verne's narration in the present tense instead of changing it to the past as the others did.

Il y a des fées, des “babes,” qu'il faut se garder de rencontrer le mardi ou le vendredi, les deux plus mauvais jours de la semaine. (II, 25-26) ... Le mardi, on le sait, est le jour de maléfices. A s'en rapporter aux traditions, ce serait s'exposer à rencontrer quelque génie malfaisant, si l'on s'aventurait dans le pays. Aussi, le mardi, personne ne circule-t-il dans les rues ni sur les chemins après le coucher de soleil. (VI, 85)

(SL) There were fairies, “babes” who should not be met with on Thursdays or Fridays, the two worst days in the week. (II, 24) ... Thursday they knew to be a day of evil deeds. Their legends told them that if they ventured abroad on that day, they ran the risk to meeting with some evil spirit. And so no one moved about on the roads and by-ways after nightfall. (VI, 75-76)

(IO) There were fairies who should not be met with on Tuesdays or Fridays, the two worst days in the week. (II, 24) ... Tuesday, they knew, was an ill-omened day. Their legends told them that if they ventured abroad on that day, they ran the risk to meeting with some evil spirit. And so, on Tuesday, nobody travelled on the roads and by-ways after nightfall. (VI, 68)

(M) There are fairies, babes, which one must be careful not to meet on Tuesday or Friday, the two most evil days of the week. (II, 27) ... Tuesday, as everyone knows, is the day of evil spells. Judging from tradition, you would be exposing yourself to encountering some malevolent spirit if you ventured forth into the countryside. So on Tuesdays no one walks on the roads or the paths after sunset. (VI, 79-80)

And sometimes Mandell fudges the different meanings of a word in Verne's text in order to bend the word's connotations to her advantage. Here's one example, where Mandell takes the French word “revenant” (meaning—as we all know from a recent Hollywood movie of the same name—“one who comes back from the dead” or a “ghost”) and renders it instead as “the walking dead,” cleverly reinforcing the book's “zombie” theme for marketing purposes.

Château abandonné, château hanté, château visionné. Les vives et ardentes imaginations l'ont bientôt peuplé de fantômes, les revenants y apparaissent, les esprits y reviennent aux heures de la nuit. (II, 25)

(SL) A castle deserted, haunted, and mysterious. A vivid and ardent imagination had soon peopled it with phantoms; ghosts appeared in it, and spirits returned to it at all hours of the night. (II, 24)

(IO) A castle deserted, haunted, and mysterious. A vivid and ardent imagination soon peopled it with phantoms, ghosts appeared in it, and spirits returned to it at all hours of the night. (II, 25)

(M) Abandoned castle, haunted castle, vision-filled castle. The lively, ardent imaginings of the people soon populated it with ghosts; the walking dead appeared there, spirits returned there during the night hours. (II, 27)

In conclusion, one of the most important underlying themes of Verne's Le Château des Carpathes—this tragic story of how Baron Gortz used technology to preserve the memory of his beloved opera singer La Stilla in his ancestral castle located near the ultra-superstitious village of Werst—can perhaps best be described as “don't jump to conclusions about what you think you see.” It seems quite fitting that the best English translation of this Verne novel is the one that you would least likely suspect—the one with the terrible title and the misleading cover descriptions.

Notes

- Arthur B. Evans. “Bibliography of Jules Verne's English Translations.” Science Fiction Studies 32.1 (March 2005): p. 105-141. ^

- Jules Verne. Le Château des Carpathes. Paris: Hetzel, 1892. ^

- Jules Verne. The Castle of the Carpathians. London: Sampson Low, trans. anon., 1893. ^

- Jules Verne. Carpathian Castle. Ed. I. O. Evans. London: Arco, “Fitzroy Edition,” 1963. ^

- Jules Verne. The Castle of Transylvania. Trans. Charlotte Mandell. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2010. ^

- This was not an inadvertent typo but an error on Verne's part that appeared in his original manuscript and in the two published editions of this novel. ^

|

|

|