Nouveaux Jonas

Chapter V of Sans dessus dessous (1889), the third of Jules Verne’s novels of the misadventures of the Baltimore Gun Club, describes reactions in the popular press to the purchase at auction by the “North Polar Practical Association” — a front for the Gun Club — of the territories north of the globe’s eighty-fourth parallel. The stated reason for the purchase seems outlandish, even by the Club’s extravagant standards: the Association plans to mine coal deposits thought to exist below the ice caps and has called for public subscribers to support this venture. (The Club’s greater, hyperborean, extravagance has yet to be revealed: they plan to melt the ice covering the coal by shifting the Earth’s axis of rotation, moving the polar regions to more temperate climes! Of course the consequences of such an event would be catastrophic for the rest of the world, and catastrophe is avoided late in the novel by a literal coup de foudre and a slip at the chalkboard that scrambles J.-T. Maston’s calculations. Long before the genre was named, Verne’s novel introduced in a lighter mood the cruel caprices of climate fiction…).

Partisans and opponents of the Association’s project have come out in full measure to praise and ridicule the methods by which the pole might be reached. Bookstores and news kiosks around the world are plastered with caricatures of audacious heroes Impey Barbicane, J.-T. Maston, and Captain Nicholl, traveling by improbable routes to retrieve the still conjectural coal. Shown with pick in hand, they dig tunnels beneath the sea and up through the ice floes. Or, after a terrifying journey by balloon, “au prix de mille dangers,” they alight at the pole to find — what disappointment! — a single chunk of coal weighing only half a pound. And then the narrative tone shifts to a different sort of drilling downward, describing not only the best of the caricatures but also the names of the newspapers in which they appeared:

On «croquait» aussi, dans un numéro du Punch, journal anglais, J.-T. Maston, non moins visé que son chef par les caricaturistes. Après avoir été saisi en vertu de l’attraction du Pôle magnétique, le secrétaire du Gun-Club était irrésistiblement rivé au sol par son crochet de métal.

Mentionnons, à ce propos, que le célèbre calculateur était d’un tempérament trop vif pour prendre par son côté risible cette plaisanterie qui l’attaquait dans sa conformation personnelle. Il en fut extrêmement indigné, et Mrs Evangélina Scorbitt, on l’imagine aisément, ne fut pas la dernière à partager sa juste indignation.

Un autre croquis, dans la Lanterne magique, de Bruxelles, représentait, Impey Barbicane et les membres du Conseil d’administration de la Société, opérant au milieu des flammes, comme autant d’incombustibles salamandres. Pour fondre les glaces de l’océan Paléocrystique, n’avaient-ils pas eu l’idée de répandre à sa surface toute une mer d’alcool, puis d’enflammer cette mer — ce qui convertissait le bassin polaire en un immense bol de punch ? Et, jouant sur ce mot punch, le dessinateur belge n’avait-il pas poussé l’irrévérence jusqu’à représenter le président du Gun-Club sous la figure d’un ridicule polichinelle [1] ?

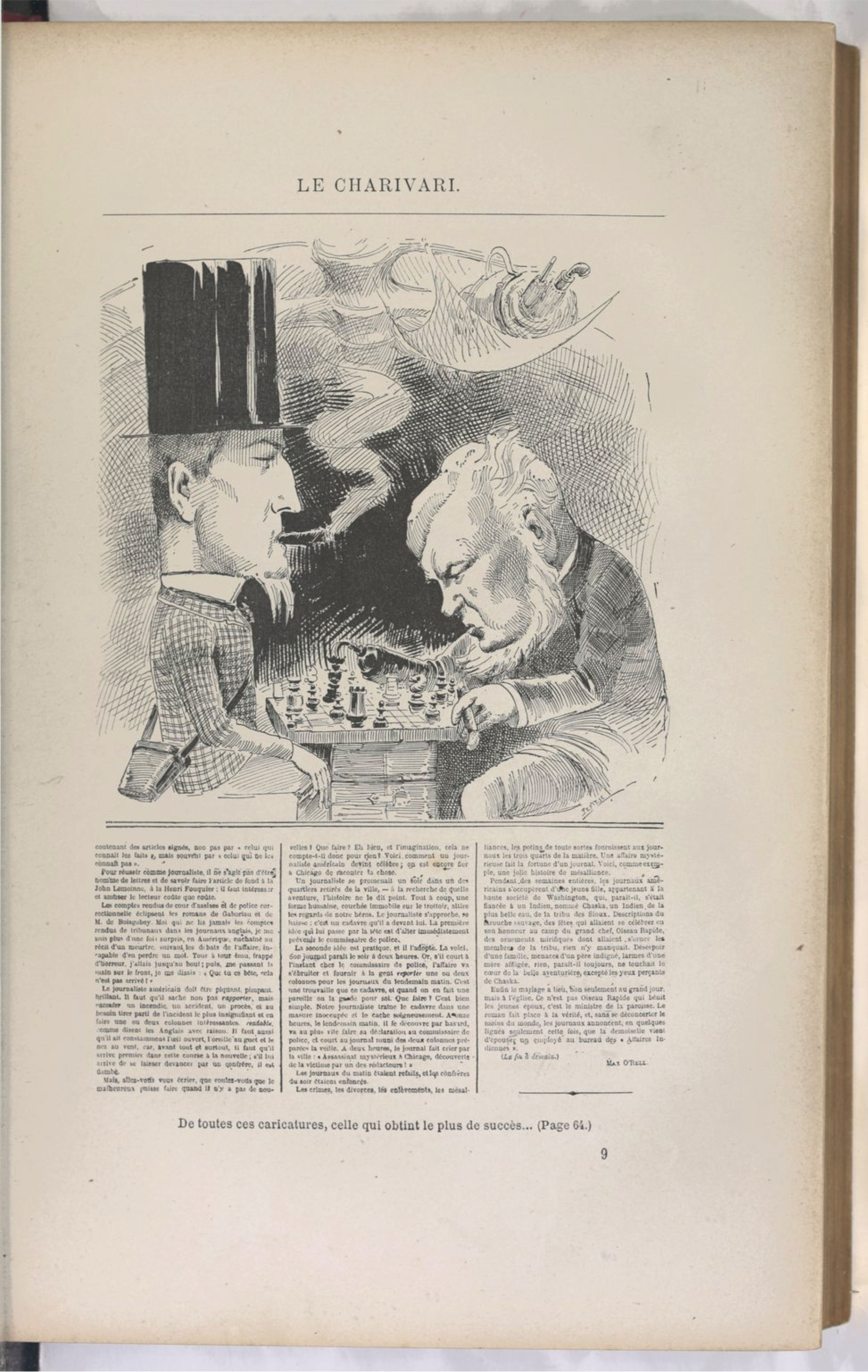

Mais, de toutes ces caricatures, celle qui obtint le plus de succès fut publiée par le journal français Charivari sous la signature du dessinateur Stop. Dans un estomac de baleine, confortablement meublé et capitonné, Impey Barbicane et J.-T. Maston, attablés, jouaient aux échecs, en attendant leur arrivée à bon port. Nouveaux Jonas, le président et son secrétaire n’avaient pas hésité à se faire avaler par un énorme mammifère marin, et c’était par ce nouveau mode de locomotion, après avoir passé sous les banquises, qu’ils comptaient atteindre l’inaccessible Pôle du globe.

In the grand octavo (gr. in-8°) editions of the novel, this passage is accompanied by an illustration, credited to George Roux, showing the most successful of the caricatures (Figure 1). Barbicane and Maston are safely ensconced in the belly of the whale. Both are furiously smoking cigars, intent on their chess game, and seem unbothered by their fantastic surroundings. The illustration includes other textual and graphic elements that one would expect to see on a newspaper page: a masthead at the top and three columns of text beneath the caricature, evidently the continuation of a story beginning on a previous page. In other words, Roux’s illustration depicts, not Barbicane and Maston inside the whale, but a newspaper that includes an image of this scene.

Figure 1. The “Stop” caricature of ch. V of Sans dessus dessous [2]. Image by George Roux (unsigned), engraving by Petit. Hetzel gr. in-8° edition, p. 65 (unnumbered). The sigle “9” in the lower right corner of the page is a signature mark, used to arrange leaves of the book in the correct order before binding.

A good number of the Hetzel illustrations include visible portions of a newspaper or magazine page [3]. Usually the page is held in a character’s hands and one or more persons are shown reading from it. Most such illustrations depict the introduction of events that kick off the adventure or the repeating of press reports of the heroes’ progress towards their destinations. In a few, persons appear to be reading recreationally, perhaps to occupy time or to keep up with events unrelated to the primary narrative [4]. Rarely are these embedded reading materials legible: usually text is figured as a series of squiggles; images are shown as the barest of outlines. In contrast, Figure 1 reproduces, with the addition of a caption at the bottom of the page, the whole of the notional newspaper page, as if it had been pasted into the reader’s copy of Sans dessus dessous; or, a more aggressive metalepsis, as if the reader were looking directly at the issue of Le Charivari described by the narrator. The columns of type below the caricature are not hand-drawn, as in nearly all images of embedded text in the Voyages; they appear to be actual newspaper print (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Enlarged view of Figure 1, showing the text below the “Stop” caricature.

In many modern reprints of the novel the image of the newspaper page is muddily reproduced and the embedded text can barely be made out. But in an original edition in good shape, it is can be read with a magnifying glass and a crucial datum is easily discovered: the author’s byline, “Max O’Rell”. Until now, no scholar has identified the source of this text and the related elements of the Stop caricature.

Sources of the Caricature

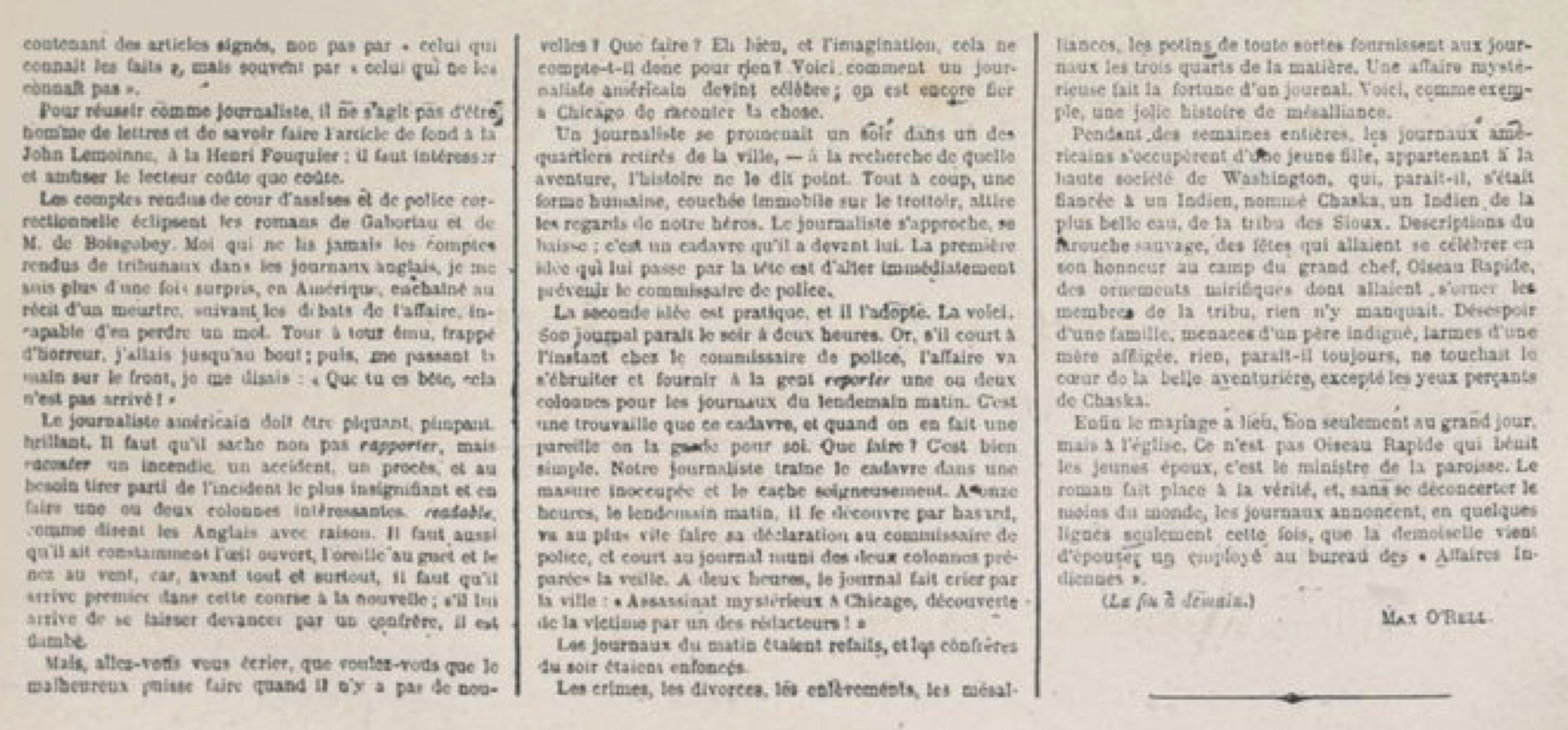

The image shown in Figure 1 is a composite of at least two sources, one of which appeared in print well before the publication of Sans dessus dessous. The drawing of Barbicane and Maston playing chess in the belly of the whale is original, fairly in the style of Stop but undeniably by Roux. The elements framing the caricature are copied from the January 28, 1889 issue of Le Charivari, the very journal in which the narrator tells us the drawing appeared (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Page 3 of the January 28, 1889 issue of Le Charivari [5]. Illustration by “Draner,” engraving by Michelet [6]. The conclusion of Part 1 of Max O’Rell’s essay “La Presse aux États-Unis” fills three columns of text below the illustration. O’Rell’s byline at the bottom of the third column and an advertisement for Hill’s Café-Restaurant, Paris, are separated by a decorative rule.

There are a few notable differences in the layout, position and sizes of the elements of the original and the faux newspaper pages:

— The image in Figure 1 is surrounded by wide margins, comparable to those used for other full-page, hors-texte illustrations in the gr. in-8° edition of Sans dessus dessous. The apparent area of the originally tabloid-size newapaper page are reduced by about 80% [7].

— The title at the top of the page in Figure 1, “LE CHARIVARI.” replaces the title in Figure 3, “ACTUALITÉS.”

— A horizontal rule has been added beneath the title in Figure 1, in keeping with a design element of most pages of the gr. in-8° edition that divides the page header (“SANS DESSUS DESSOUS”) from the body text. This rule does not appear on the remaining seven full-page illustrations of the edition, nor on the first full page of the body text (page 1), which is ornamented with a 2/3 page illustration that includes the book’s title. This is the only page of the body of the novel after page 1, apart from the other full-page illustrations, in which the header is not “SANS DESSUS DESSOUS.”

— In Figure 1, the number “18” appearing in the upper right margin of Figure 3 has been removed. This is not a page number but an enumeration of the cartoon in the “ACTUALITÉS” series.

— The Stop caricature completely replaces the image in Figure 3, the heavy double rectangles enclosing it, and the caption beneath. There is no caption beneath the caricature, above the three columns of text. A brief quote from Verne’s text, “De toutes ces caricatures, celles qui obtient le plus de succès… (Page 64.)” as been added beneath the nozional bottom edhe of the embedded page. This is typical of hors-texte illustrations in the Hetzel editions.

— Most elements in Figure 1 below the caricature, including the double horizontal rules that divide it from the three columns of text making up the bottom third of the page, are unchanged from Figure 3. Exceptions include the small block of advertising beneath the decorative rule at the end of the rightmost column (the advertisement has been omitted) and the position of the decorative rule (it has been shifted to the baseline of the two leftmost columns).

On their surface, these changes and substitutions appear to be mostly technical solutions related to the conceit of the embedded page: the narrator reports that a caricature of the Gun Club heroes appeared in an issue of Le Charivari; Roux or someone else determined to place his drawing within a reproduction of an actual page of that newspaper; minor changes were made to the composited image page to reinforce the conceit and perhaps obscure the borrowing. And we know that in later novels of the Voyages extraordinaires it was not unusual for the publisher to insert graphic elements, even full page images, that were not created by the credited illustrators (Harpold 2015). In this case however, the compositing of credited and uncredited material — more precisely, credited and uncredited in a reversal of the usual method — is unique; there is no other image like it in all of the illustrated Voyages. It is also, I will argue, exemplary of important aspects of the method of the Hetzel-Verne image-texts. This becomes clearer if we parse out the literary, historical, and cultural sources of the illustration’s several parts.

Le Charivari

The four-page, tabloid-format daily satirical newspaper — the first daily illustrated newspaper in France — founded in 1832 by caricaturist, lithographer, and editor Charles Philipon (1800–1862), journalist and novelist Louis Desnoyers (1805-1868), and Philipon's brother-in-law Gabriel Aubert, principal of the publishing house Aubert et Cie.

Figure 4. Masthead of the January 28, 1889 issue of Le Charivari. Lithograph by Grandville

Two years before Philipon and Aubert had founded the satirical weekly La Caricature [8].) Philipon was Le Charivari’s editor in chief from 1831 to 1835. At the time of the publication of the Stop caricature, writer, journalist, and librettist Pierre Véron (1833–1900) was editor of both Le Charivari and Le Journal amusant, an 8-page weekly satirical magazine also founded by Philipon (in 1856) and edited by him until his death in 1862 [9]. Le Charivari would continue to be published under a series of different editors as a daily newspaper through 1926, and then weekly until 1937.

The period from the early 1830s through the end of the First World War represented the golden age of caricature in France, during which the art form achieved an importance never again equalled in the nation’s culture [10]. Reliable barometers of the power of the press in the changeable French political landscape, and subject to harsh censorship by the left and right, satirical depictions of kings, emperors, ministers, military officers, and their minions were often targets of official invective and prosecution. For much of the 19th century published drawings, posters, and theatrical performances were singled out for prior censorship and legal sanction — long after limits on other forms of political speech had been abolished in 1821 — because they were considered political actions (not protected opinions), and were thought by the ruling elite to be especially likely to incite revolutionary sentiments among the lower classes [11]. Their concern was not misplaced; despite pressure on editors and artists (seized equipment, frequent fines, jail sentences) satirical images were among the chief instruments by which the press helped to discredit and to bring an end to the July Monarchy, the Second Empire, and the monarchist period of the Third Republic.

After the liberalization of press laws in 1881, caricatures and satirical journals increased in number during the final decades of the century and continued to play important roles in reflecting and shaping French popular opinion. This was particularly true during the Boulangist crisis, the Dreyfus Affair, and the anticlerical debates of the first decade of the new century. During the War, many French satirical journals suspended publication; most of those that remained active were aligned with the patriotic consensus. After the War, interest in humorist periodicals declined as new forms of popular entertainment, notably radio and cinema, took their place [12]. Though caricature and satire remain visible elements of French political discourse, and move for awhile to the foreground in times of crisis (e.g., following the 2011 and 2015 terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo), they have much less influence in France today than they had during Verne’s lifetime.

Philipon was the most prominent French publisher of political caricature of the mid-19th century; La Caricature and Le Charivari were the most influential, and Le Charivari the longest-lived, of the satirical journals of the period (Goldstein 1989, Kerr 2000). They shared, with other journals edited and published by Philipon and Aubert, a stable of talented and celebrated artists. Among those contributing lithographs, woodcuts and (after 1870) zincographies (gillotages) to the pages of Le Charivari were Cham (Amédée de Noé), Honoré Daumier, Achille Devéria, Gustave Doré, Draner (Jules Jean George Renard – see below), Paul Gavarni (Sulpice Guillaume Chevalier), André Gill [13], J.J. Grandville (Jean-Ignace-Isidore Gérard Grandville), Alfred Grévin, Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), and Stop (Louis Pierre Gabriel Bernard Morel-Retz — see below).

Both La Caricature and Le Charivari published fierce political satire during the journals’ early years, especially during the July Monarchy [14]. But in general the subjects of caricatures and articles in Le Charivari were more varied and less politically-charged, and for the most part it evaded the sanctions that forced the closure of its sister publication in 1835 and 1843. By 1889, the “Actualitiés” series of cartoons on page 3 of each issue was, like a rising proportion of the satirical press, devoted mostly to caricatures of types and la satire des mœurs: humorous vignettes of modern life, the peccadilloes of high society and the bourgeoisie, the hypocrisies of the professional classes, etc. [15] Figure 3, depicting an exchange with one of Paris’ notoriously reckless coachmen — “And if you should run over a pedestrian?” “That wouldn’t bother me very much; we’re insured” — is typical of this kind of illustration [16].

Draner

The cartoon in Figure 3 was drawn by Draner (Jules Jean George Renard, 1823–1926), a Belgian-born illustrator and caricaturist [17]. A self-taught artist, in 1861 he moved to Paris to pursue a career in industry — eventually rising to become Secretary of the Société des Zincs de la Vieille-Montagne but his chief occupation in later life and his passion appears to have been caricature, especially of military figures. (His Types militaires: Galerie militaire de toutes les nations, 1862–71, is considered a classic of this genre.) His illustrations were published in leading Parisian journals of the late 19th century, including Le Monde comique, Le Journal amusant, Le Petit Journal, L’Illustration, and L’Univers illustré. In 1879, he replaced “Cham” (Amédée de Noé) as Le Charivari' in-house caricaturist for the “Actualités” page. Draner was known also for his design of theatrical costumes, in particular those for the opéra-bouffes of Jacques Offenbach, including the latter’s 1877 three-act opera of Verne’s Docteur Ox. An ardent French nationalist and Germanophobe, Draner’s defiant Antidreyfusard stance appears to have closed the doors of many journals to him after the mid-1890s but he continued to publish in Le Charivari until about 1900 under the pseudonym “Puf.” [18]

Stop

Though no artist’s signature appears in the image, the narrator of Sans dessus dessous observes that the caricature of Barbicane and Maston is “sous la signature” of Stop (Louis Pierre Gabriel Bernard Morel-Retz, 1825–99) [19]. A French painter, caricaturist, and engraver, Morel-Retz was first trained as a lawyer (he earned his Doctorat en droit from the Université de Dijon in 1849), and served for a time in the Conseil d’État in Paris. By the mid 1850s, he had abandoned law for a professional career as an artist, training under Charles Gleyre at the Académie des Beaux-Arts and presenting his paintings, aquarelles, and engravings at several Salons de Paris through the mid-1860s [20]. Morel-Retz is best known for his work in L’Illustration, Musée des familles, Journal amusant, and Le Charivari. Several series of his illustrations were collected in books published during his lifetime, including Bêtes et gens (1876), Ces Messieurs (1877), and Nos Excellences (1878). A talented musician, he was the composer of operettas and playlets, and was a costume designer for lyric dramas and opéras comiques by Félicien David and Charles Lecoq [21].

Max O'Rell

The three columns of text below the Stop caricature are signed with the pen name of the Franco-British author, journalist, and foreign correspondent Léon Paul Blouet (1847–1903, Figure 5).

Figure 5. Léon Paul Blouet (“Max O’Rell”), c. 1902. Woodcut by unknown engraver. Source: Figures contemporaines tirées de l’Album Mariani, vol. 7, no pag. (“A Monsieur Mariani, Votre vin est positivement merveilleux…” Jules Verne was also an avowed enthusiast of Angelo Mariani’s cocaine-fortified wine [22].)

Though largely forgotten today, at the end of the nineteenth century Blouet, sometimes referred to as “the French Mark Twain,” was among the best-known French writers in the world [23]. Educated at the Sorbonne and the École Militaire (he graduated as a lieutenant in the French artillery), Blouet served during the Franco-Prussian War. He was taken prisoner at Sedan (1870) and on his release was returned to Paris to fight against the Commune. Wounded during that conflict and honorably discharged, he moved to London in 1872 to take a post as a French instructor at St. Paul’s London school for boys. In 1883 his first book, John Bull et son île was published in Paris. A witty send-up of British culture and politics, John Bull was an immediate bestseller in France — the book went through 57 French editions and sold more than 600,000 copies in only two years — and was soon translated into English, becoming also a bestseller in Great Britain and the United States. By 1896 it had been translated into 17 languages.

Between 1884 and 1903 Blouet published thirteen further collections of humorous anecdotes concerning French, British, and American “morals and manners,” all respectable bestsellers and most published simultaneously in Paris, London, and New York [24]. He was a regular contributor to leading French, American, and British magazines such as the North American Review, Harper’s Weekly, Cosmopolitan, and La Revue de Paris, and wrote columns for Le Figaro and the New York Journal. He toured widely, giving more than 2500 public lectures in the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. An advocate of using the press to mediate Anglo-French differences, Blouet was featured prominently in American and British reports of the Dreyfus Affair — a Dreyfusard, he counseled foreigners to remain neutral to avoid an escalation of French anti-semitism — and of the 1898 Fashoda Crisis, during which he urged détente between the British and French. His death in 1903 was reported in many American and British newspapers; less notice was taken by the French press.

If it was not made casually, the selection of Blouet as a journalistic context for the Stop caricature appears appropriate in several respects. Blouet’s career and writings were directly shaped by transnational exchanges of the aspirations and anxieties of middle-class European and Anglo-American readers, made possible by recent advances in oceanic and railway transport, telecommunications, and by the growing importance of journalism as an arbiter of national and class identity. These same transformations of communication and society also strongly influenced the arc of Verne’s writerly project. In novels such as L’Ile Mystérieuse (1874), Michel Strogoff (1876), Claudius Bombarnac (1893), Le Testament d’un Excentrique (1900), and all three of the Gun Club stories (but above all in Sans dessus dessous), the emerging global network of mass communications and the activity of a journalist-adventurer, or more abstractly the activity of a journalistic self-consciousness, define the messages of the novel [25]. Similarly, Blouet’s solidly bourgeois positions on the role of religious authority, the patriarchal foundation of the family, and the emancipation of women are not far removed from Verne’s viewpoints on these matters. The slight mutations of these 19th century cultural norms in Verne’s fiction rarely call them into question; they are a staple of his depictions of family and social life. Relatedly, both authors often rely on national, ethnic, and class stereotypes as shorthand versions of unacknowledged assumptions about normative social relations.

In point of fact, Blouet was no French Twain. He shared few of Twain’s progressive political and economic ideas and even less the American author’s rejection of his era’s racial, social, and sexual conventions [26]. Blouet was critical of the intellectual stupor and social vices of British colonial life in Australia and South Africa, but largely silent on the French colonies, and was in general supportive of European colonial expansion in Africa and Asia. Verne’s assessments of the depredations of 19th century colonialism were more strongly disapproving but inconsistent; he was also prone to overlook French colonial excesses. Twain’s thundering, unwavering opposition to the New Imperialism stands in stark contrast to the attitudes of the two French authors. In his “morals and manners,” then, Blouet was plausibly closer to Verne than to Twain.

The signal difference, irreducible, between the three authors lies in the qualities of Blouet’s art. He was an undistinguished stylist, jovial and rarely capable of writing in another mood, more limited by his satirical impulses than inspired by them. One who capitalized unreflectively on the collective social anxieties of his time, he offered no antidotes to the moral shortcomings of his contemporaries, nor did he make an effort to reimagine their lives in new literary terms. Twain and Verne, in contrast, were innovators in this respect. In Blouet’s writing there is none of the sharp, sly bite of Twain’s satire nor anything resembling Verne’s ambiguous dark humor, as in a novel like Sans dessus dessous. His two attempts at long fiction, novels on “women’s concerns” published late in his life, were critical and commercial failures. Apart from some common ground in the authors’ bourgeois sensibilities, the connection between Blouet’s text and Roux’s image, and through the latter to Verne’s novel, is primarily one of tone or satirical inclination, not of artistic or literary ethos.

“La Presse aux États-Unis” was published in Le Charivari in two parts, on January 28 and 29, 1889. The text reprinted below the Stop caricature is the conclusion of Part 1 [27]. The essay was reprinted, with minor changes, in chapter XVIII of Blouet’s sixth book, Jonathan et son continent (1889) [28]. The essay is typical of his depictions of the contradictions of American culture. Poking fun at the public’s appetite for scandal and spectacle, and the priority of newspaper sales and journalistic carreerism over truthful reporting, it is very nearly the sort of yellow journalism it lampoons.

Hill’s Café-Restaurant

The advertisement for Hill’s appearing in the lower right corner of Figure 3 is deleted from Figure 1. Also known as “Hill’s Tavern,” this café located on the Boulevard des Capucines specialized in English food and drink and was famous, or perhaps infamous, for its private rooms named after the English poets, which remained open for a well-heeled and demimondaine clientèle long past the official 2 AM closing time (Gonzalez-Quijano 2013). Frequented during the day by mostly British expatriates, in the evening it was, in the words of essayist and critic Orlo Williams, “invaded by Bohemia, and was often so full that its doors had to be closed” (261). Hill’s was near to Nadar’s studios (35, Noulevard des Capucines), and the French photographer, caricaturist, balloonist — and close friend of Jules Verne — was a frequent visitor (Delvau 157) [29].

In 1889, the building housing Hill’s Tavern was also home to the newly-opened Théâtre des Capucines. Located in the central courtyard of the building, the theatre had been designed by Édouard-Jean Niermans, the Dutch-born architect responsible for many brasseries and theaters of Belle Epoque Paris. Renamed the Théatre Isola in 1892, it remained a performance space for operettas, musical comedy, and French popular music until 1970, when the building was purchased by perfumer Fragonard. In 1993, the theatre space was converted to a perfume museum, the Théâtre-Musée des Capucines.

The Verne–Hetzel, fils–Roux Relay

Most of the details regarding the caricatures described in Chapter V, as well as the names of the journals in which they appeared, were added to Sans dessus dessous sometime after Verne submitted the only known manuscript to Louis-Jules Hetzel. (See Appendix A.) It is difficult to determine when and by whom the new information was added, or the exact chain of events leading up to this addition and the pairing of the passage with the Stop caricature. In the remainder of this essay I offer some conjectures regarding the emended passages and the method by which the illustration was created, and tentative observations regarding the wider significance in Yerne's œuvre.

I am unaware of any published communications between Verne, his publisher, or his illustrator regarding the Stop caricature. We know that collaborations on the novels’ illustrations were common, but there is no trail of correspondence in this case [30]. Neither Stop nor Le Charivari is mentioned in the published Verne–L.-J. Hetzel correspondence of the period (Verne et al. 2004). Neither the name of the caricaturist nor that of the journal appear anywhere else in Verne’s published fiction. But there can be no doubt that Verne was aware of Le Charivari. The journal was widely read and its contents frequently discussed in the press. Its Editor-in-Chief, Pierre Véron (1833–1900), was an old friend of Verne and a sometimes participant in the soirées of “Les Onze sans femmes,” the bachelors’ dining club Verne founded while living in Paris in the 1850s. And Stop had been one of the founding members of “Les Onze” (Butcher 118)! Even if someone else — Hetzel, perhaps — added mentions of Stop and Le Charivari to a later manuscript than the one we know of, or to an intermediate proof, Verne likely was aware of or would have approved of these additions.

The image of Barbican and Maston traveling northward in the belly of the whale is memorably comic and it is easy to imagine that Hetzel, or Verne by way of Hetzel, suggested to Roux that this passage would be a good one to illustrate. Roux might have been given instructions to create an image in the style of a caricaturist such as Stop. Or perhaps Roux elected to emulate Stop on his own initiative and the evident success of the image led to the decision to incorporate the caricature in a facsimile of a journal where Stop might have been published. Verne’s addition to the MS of a line describing the Nouveaux Jonas “attablés et jouant aux échecs” (see below, Appendix A) may have been made in response to the caricature: he strikes out another phrase, now mostly illegible, that appears to describe Barbican and Maston before a door or a window in the whale’s belly (?); the manuscript addition could have been made in response to the caricature, or the caricature drawn in response to the addition. Mention of the journal in the published text, directly associating the composite illustration with the narrative (“Mais, de toutes ces caricatures, celle qui obtint le plus de succès fut publiée par le journal français Charivari…”), was inserted at a later point, perhaps in response to a decision to create the facsimile page, perhaps in response to the finished illustration. Textual details that might clarify this sequence of events are not preserved in Verne’s manuscript.

The published correspondence between Verne and L.-J. Hetzel gives us clues regarding the wider timeline of these revisions and additions [31]. The first mention of Sans dessus dessous is in a letter from Verne to Hetzel dated April 18, 1888, when the author writes that he is “en plein dans le Redressement d’axe [an early working title of the novel], à la fois effrayé et emballé” (CI 82). He has evidently been working on the project for some time, because the letter also mentions Albert Badoureau’s “gigantesque” essay-in-progress on the practicability of the Gun Club’s method, which we may imagine Verne discussed with Badoureau not long before Verne had worked out at least the major plots points [32]. Verne mentions his progress on the novel briefly in two letters (August 9, 1888, CI 86; October 8, 1888, CI 88); on October 29, 1888 (CI 91), he announces to Hetzel that he has just sent the editor the completed manuscript. Their subsequent correspondence regarding the novel up until its publication in November 1889 is chiefly concerned with: the title (Hetzel proposes the punning Sans dessus dessous); several back-and-forth exchanges of revisions; an unsuccessful attempt to find a journal that might publish a serialized version; and Badoureau’s supplemental chapter, which Verne wanted included in all editions but which appeared only in the octodecimo édition originale (see Appendix A).

During the month of January 1889 Verne is in Cap d’Antibes on a working vacation at the home of Adolphe d’Ennery, with whom he is collaborating on a stage adaptation of Les Tribulations d’un Chinois en Chine. On January 1, he writes to report that he has received Hetzel’s notes on the manuscript and is in the course of a “gros travail” revising Sans dessus dessous (CI 95). He promises to send the results in a few days. On January 26, Hetzel, having read the revised draft, writes to Verne his longest letter on the subject of the novel. He celebrates the current version’s greater vivacity and predicts its success but notes several weaknesses still in need of correction [33]. Verne replies on January 29 — the day after the publication of the issue of Le Charivari that would be incorporated into the Stop caricature — defending several of his writerly choices but asking Hetzel to send to Amiens by priority mail a corrected proof along with another marked-up copy including the editor’s observations (CI 98–99). Following his return to Amiens, Verne writes in a letter of February 2 that he has received the proofs and commits to making further corrections informed by Hetzel’s criticisms (CI 100). On February 6, he writes that he is “tellement préoccupé du Sans dessus dessous que je me suis remis aux épreuves, avant de commencer la pièce chinoise,“ the stage adaptation he is working on with D’Ennery (CI 100). On April 8, he writes again to Hetzel, enclosing a revised proof of the novel that he hopes will be the next-to-final version. He requests a final proof to be returned to him in order to verify that all previous corrections have been made (CI 101). Verne remains concerned on this account nearly until the novel’s publication, asking Paul Simon, Hetzel’s assistant, and later Hetzel, twice more for copies of the latest proofs, in letters of May 2 (CI 104) and September 4 (CI 104) [34].

When did Roux begin work on the illustrations for Sans dessus dessous? He could not have done so before early November 1888, as Hetzel had not yet received a copy of the manuscript. In response to Hetzel’s first comments, Verne substantially revised the manuscript between November 1888 and early January 1889; Hetzel says of the second version “vous avez complètement bouleversé votre texte sinon la marche même du roman” (CI 96). It seems likely, then, that Hetzel waited until early 1889 to set his in-house artist at work on the illustrations, because the fluid state of the manuscript up to that point would have jeopardized the relevance of completed drawings.

The publication date of the Le Charivari page incorporated into the Stop caricature, January 28, 1889, presents a challenge to this conjecture. It is possible that Roux or others who may have worked on the composite illustration assembled its elements weeks or months after January 28, perhaps taking up a copy of the journal that was filed away or had been for some reason set aside in the artist’s atelier. That there is no direct connection of the content of the Stop caricature and the content of O’Rell’s essay suggests that the January 28 issue was chosen casually: an example of a satirical journal that would be familiar to Verne’s readers, with a page layout suited to the substitution of Roux’s drawing for Draner’s. But a case can, perhap more convincingly, be made that a choice of this page of this issue of this journal (and of a text of this author) was more likely to happen when the issue was still current, when perhaps the layout of the page or the mood of O’Rell’s text were still fresh in the artist’s mind; as I have suggested above there are reasons to associate the cultural-medial contexts and some thematic elements of Verne’s and O’Rell’s writing. If Roux was responsible for the compositing of the elements, he could have drawn the caricature and assembled the illustration after January 28, but probably before several months had passed. Despite precise knowledge of the dates involved, uncertainties remain.

Without careful analysis of the original art it is difficult to determine how and in what order the elements of the composite image were created, assembled, and printed [35]. Unlike other work by Roux for Hetzel et Cie, the caricature is not signed by the artist, probably to help sustain the notion that the it was drawn by Stop. (The signature of the engraver, Petit, is legible below J.T. Maston’s left thigh [36].) The lines of the caricature are bolder, the shapes simpler, and the tonal ranges less subtle than in other illustrations in the novel; this is mostly an effect of Roux’s imitation of Stop’s style, but it may also give some indication of how the illustration was assembled. The caricature is engraved — we have the engraver’s signature to show this — but the dark blacks of Impey Barbicane’s hat, the strap crossing his jacket, the background behind the chess players, and several of the chess pieces appear to have been inked over. It is vanishingly unlikely that Roux or the printer had access to original relief plates of the January 28, 1889 issue of Le Charivari, so the text of the O’Rell article must have been reproduced in the illustration by a photolithographic method [37]. Visual artifacts in the reproduced text, small inkblots and filled-in letterforms showing some degradation of the image, justify this conjecture. But why not use photolithography for the entire illustration from the start — that is, why not paste Roux’s original drawing onto a page of Le Charivari, obscuring Draner’s image, make a few other changes, and reproduce the whole as a single image? The evidence that the image of Barbicane and Maston in the belly of the whale was engraved suggests that a baseline caricature was created independently of its incorporation into a facsimile page of Le Charivari, perhaps independently of a decision to incorporate it into a facsimile page at all. The final version of the illustration was assembled through some combination of lithographic and relief methods, probably including conversions of some elements of the page from one method to another.

Reality Effects

The Stop caricature is unique among the illustrations of the Voyages extraordinaires in the manner in which it was assembled. It also exemplifies feedback systems of images and texts that are typical of, even fundamental to, Verne’s illustrated fiction.

The principle at work here is simple but its consequences are far-reaching. The additional level of detail in the published passage describing the Barbicane and Maston caricatures — which may or may not have been prompted by the illustration, or which may have prompted the creation or compositing of the illustration — enlarges upon Chapter V’s description of press reactions to the Gun Club’s purchase of the polar territories. Mentions are made in the text of real satirical journals of the period (Punch, La Lanterne magique, Le Charivari) which would likely comment on such a scheme; also mentioned is a well-known artist, Stop, who might very well have drawn an image of the kind described and whose works had been previously published in Le Charivari. Roux’s drawing of Barbicane and Maston in the belly of the whale (the Stop caricature, strictly speaking) is fitted into the framework of a realistic-looking — in fact, a real — page of Le Charivari, apparently embedded in the gr. in-8° edition of Verne’s novel [38]. Though more complexly-enacted than usual, there is nothing out of the ordinary in this use of such realist stage machinery; certainly not in Verne, whose fiction relies on extradiegetic props such as these more often than we can probably count. What is uniquely true in this case is the degree to which the puckish extremity of the image narrated and the image shown, and described and shown in eminently realist ways — but in ways not essential to the story — turns the whole outlandish enterprise of Sans dessus dessous (intra- and extradiegetically signified) into something hybrid and unstable. The framework of the (real) newspaper page is not, or is only marginally, a part of the story (the narrator mentions the name of the newspaper but no one but Verne’s reader is given to read from the page), but neither is it window-dressing. The real parts of the embedded page — those borrowed from a real issue of a real newspaper — belong, I would say, to that category of signifiers that Roland Barthes (1968, 1986) terms notation; they have no predictive value, they don’t advance any aspect of the adventure; we can easily imagine Roux’s comic drawing recapitulating the narrator’s remarks in the text without the framework. (It would still be funny but it wouldn’t be the same, of course, and that’s the point.) Such elements of the text, or in this case the image and the text, are simply present: residues of a gentle brush against reality that don’t do anything else, serving thus as indicators of a reality effect that indexes other aspects of the whole [39]. But because every other aspect of the image is plainly unrealistic (the drawing at the center of the illustration is a satirical depiction of two fictional heroes on an impossible journey), the compositing permits things to go both ways. The purest fantastic — the whole of the adventure, not just an improbable journey north in the belly of the whale, both presented to us in a humorous and a realist voice — is supported by the reality effect of the embedded page and the reader’s grasping of its seeming verisimilitude, and by the absurdity of the scene embedded within that page — and, indirectly, by the idea of satirizing two men who don’t really exist. By dint of this self-aware, nearly self-parodying, framing the novel’s hint of realism is, in effect, caricatured.

Given the prominence of caricature in French culture during Verne’s career as an author, his ties to artists and editors who were celebrated or harassed for their contributions to the art form, and the fundamental role of illustration (and in select examples, of obvious caricature) in his published fiction, it is curious that Verne mentions caricature only a few times in the texts of the Voyages [40]. The passage describing the Stop caricature is by far the longest, most detailed discussion. Compare it, for example, to a passage in De la Terre à la Lune recounting responses in the press to the announcement of the planned rocket launch:

on peut le dire, jamais proposition ne réunit un pareil nombre d’adhérents; d’hésitations, de doutes, d’inquiétudes, il ne fut même pas question. Quant aux plaisanteries, aux caricatures, aux chansons qui eussent accueilli en Europe, et particulièrement en France, l’idée d’envoyer un projectile à la Lune, elles auraient fort mal servi leur auteur ; tous les « lifepreservers » du monde, eussent été impuissants à le garantir contre l’indignation générale. Il y a des choses dont on ne rit pas dans le Nouveau Monde. Impey Barbicane devint donc, à partir de ce jour, un des plus grands citoyens des États-Unis, quelque chose comme le Washington de la science, et un trait, entre plusieurs, montrera jusqu’où allait cette inféodation subite d’un peuple à un homme. (ch. III)

In the Hetzel edition of that novel, this passage is accompanied by no illustration of the “plaisanteries… caricatures… chansons” that greeted the announcement. Similarly, in the final chapter of Sans dessus dessous, following the catastrophic failure of the Gun Club’s effort to alter the Earth’s axis (attributable perhaps to a heavenly intervention and more surely to a fortunate parapraxis), Barbicane, Maston, and their comrades are again subjected to public ridicule —

Si jamais la risée publique se donna libre carrière pour accabler de braves ingénieurs mal inspirés, si jamais les articles fantaisistes des journaux, les caricatures, les chansons, les parodies, eurent matière à s’exercer, on peut affirmer que ce fut bien en cette occasion ! Le président Barbicane, les administrateurs de la nouvelle société, leurs collègues du Gun Club, furent littéralement conspués. On les qualifia parfois, de façon si … gauloise, que ces qualifications de sauraient être redites pas même en latin — pas même en volapük [41]. (ch. XX)

Greater ridicule, then, than before the blast, but noted in the text avec peu de détails. (And again, without a graphic correlate: perhaps a sign of artistic-editorial discretion, given the gauloiseries alluded to in this case?) What we do get by way of supplement to the list of brickbats are lyrics to a song said to have been written by Paulus, one of the (real) stars of the Paris café-concert scene [42].

Figure 6. Jean-Paul Habans (“Paulus”), n.d., photographer unknown. From the private collection of Volker Dehs, reproduced with his kind permission.

Pour modifier notre patraque,

Dont l’ancien axe se détraque,

Ils ont fait un canon qu’on braque,

Afin de mettra tout en vrac !

C’est bien pour vous flanquer le trac !

Ordre est donné pour qu’on les traque,

Ces trois imbéciles !... Mais... crac !

Le coup est parti... Rien ne craque !

Vive notre vieille patraque !

Grist for the reality effect’s mill, but reported not shown, and tame by comparison to the Stop caricature.

The passage and the caricature stand apart in another respect. Sans dessus dessous is run through with many of Verne’s sharpest observations on the press’s role in shaping popular attitudes towards political, economic, and (to a degree that has few equivalents in the Voyages) scientific hubris. The three satirical journals mentioned in the passage on the Stop caricature differ in how they would likely respond to such overweening pride, from the ninety or so “serious” newspapers listed in ch. XVI — “le chœur des mécontents va crescendo et rinforzando” — in which the pros and cons of the Gun Club’s scheme are also discussed. There the tone is outraged but more or less well-reasoned (the scheme is bold but the consequences of success would be disastrous); in chapter V, the tone is over the top, sarcastic, burlesque, and for that the more important to the reader’s understanding of the meaning of the novel than her possible sympathies, in good humor or not, with expressions of admiration or outrage. The space given thus to explicit satire in word and image, and the unique force of the Stop caricature’s image-text, justify I think, François Raymond’s assertion (1976) that the passage is the exemplary moment of the novel; and not only of the novel, but perhaps also of the Voyages extraordinaires:

Quoi de plus ‘extraordinaire,’ en effet, que les cinq voyages ainsi esquissés? et quoi de plus vernien, que ces personnages qui allument des brasiers pour les mieux traverser (Les Enfants du capitaine Grant, Michel Strogoff), se font transporter dans ‘L’estomac… comfortablement meublé et capitonné’ d’un obus ou d’un éléphant, d’une baleine ou d’un Nautilus? ou, inversement, voient le prix de la course se volatiliser (L’Étoile du Sud, Antifer, Le Volcan d’or) — à moins qu’ils ne restent piégés par le but, tel J.–T. Maston rivé au ‘Pôle magnétique’ par son crochet de métal, charge anticipée du futur Sphinx des glaces?

En ces ‘caricatures,’ Verne ne fait donc rien de moins que doubler l’ensemble des ‘Voyages extraordinaires’ de leur envers parodique; redoubler la représentation du projet idéologique de son époque; la conquête du globe, par la systématique démystification de ce même projet, qu’il montre voué à l’alternative du fantasme ou de l’échec. De la ‘Lanterne magique’ de l’idéologie, au ‘Stop’ qui lui oppose ses limites, les noms donnés par Verne sont la pour le confirmer; comme pour donner le ton, et devancer Roussel, sont évoqués ce ‘Punch’ — à la fois océan d’alcool enflammé, parangon des journaux humoristiques, et version anglaise de ‘polinichelle’ — et son rival français qui, comme par hasard, s’appelle, lui, ‘Le Charivari’ (187–88) [43].

Now, it must be admitted that Raymond’s broad analogy is weakened by the variance of the published version from the last known manuscript of the novel. When were the allusions to the satirical journals added to the text? When were the details of the caricature matching the composited illustration added? By whom and with whose authority? Raymond doesn’t seem to be aware of these problems or of the multiple intertexts joined to the faux newspaper page. But these facts of the caricature’s complex, messy production don’t inhibit its potential to support a version of the analogy, once we recognize that the success of the reality effect to demystify, rather than to fantasize or falsify, depends here on how well one marks both the banal presentation of a wisecrack (a caricature in a satirical journal looks like this), and the extreme ambiguity of the wisecrack’s wider message (if you do your math correctly, shifting the earth’s axis is less outrageous than traveling to the pole in the belly of a whale.)

In the larger system of correspondences that it enables, the confection of the Stop caricature points to the wisdom of Raymond’s related claim that Sans dessus dessous may be the most resolutely modern of Verne’s novels (181). The caricature is not a pastiche of a page of the leading satirical French journal of the period; it is a page of the journal, or as close to a version of this as can be constructed in the open-ended medial universe of the published Voyages, composited from an actual newspaper page (and all the historical and cultural resonances that this precise, material page conveys), and the work of an illustrator (Roux) who seems never to have been published in that newspaper, in the style of another illustrator (Stop) who was. And this complex, finally unstable equation (Figure 1 is a page of the journal and is not a page of the journal, exists in the diegetic universe of the novel and, credibly, in the hands of the reader) is presented in a spirit of satire that is modern because it is (resolutely, cannily) polymedial: a détournement of the actual in service of the imaginary, with a healthy disregard for petty obligations of realism, such as the requirement that such a verisimilar prop should bring anything else to an equilibrium. The Stop caricature can be read as an emblem of the relays of image and text, and intra– and extradiegetic elements, of the Voyages extraordinaires, and of the diverse array of objects that drift, inconstantly, between such notionally polar opposites.

Appendix A — Manuscript and published variants of the “Stop” passage

The first unserialized publication (the so-called édition originale) of Sans dessus dessous was in an unillustrated octodecimo (in-18) edition, on November 7, 1889. Two grand octavo (gr. in-8°) editions, including 36 illustrations by George Roux, were published on or soon after November 18, 1889: a “simple” volume containing only the novel, and a “double” volume including also Le Chemin de France and the short story “Gil Braltar.” Unusually, Sans dessus dessous appears not to have been published in a prior serialized version [44]. The published passages describing the Barbicane and Maston caricatures are identical in the in-18 and the gr. in-8° editions [45].

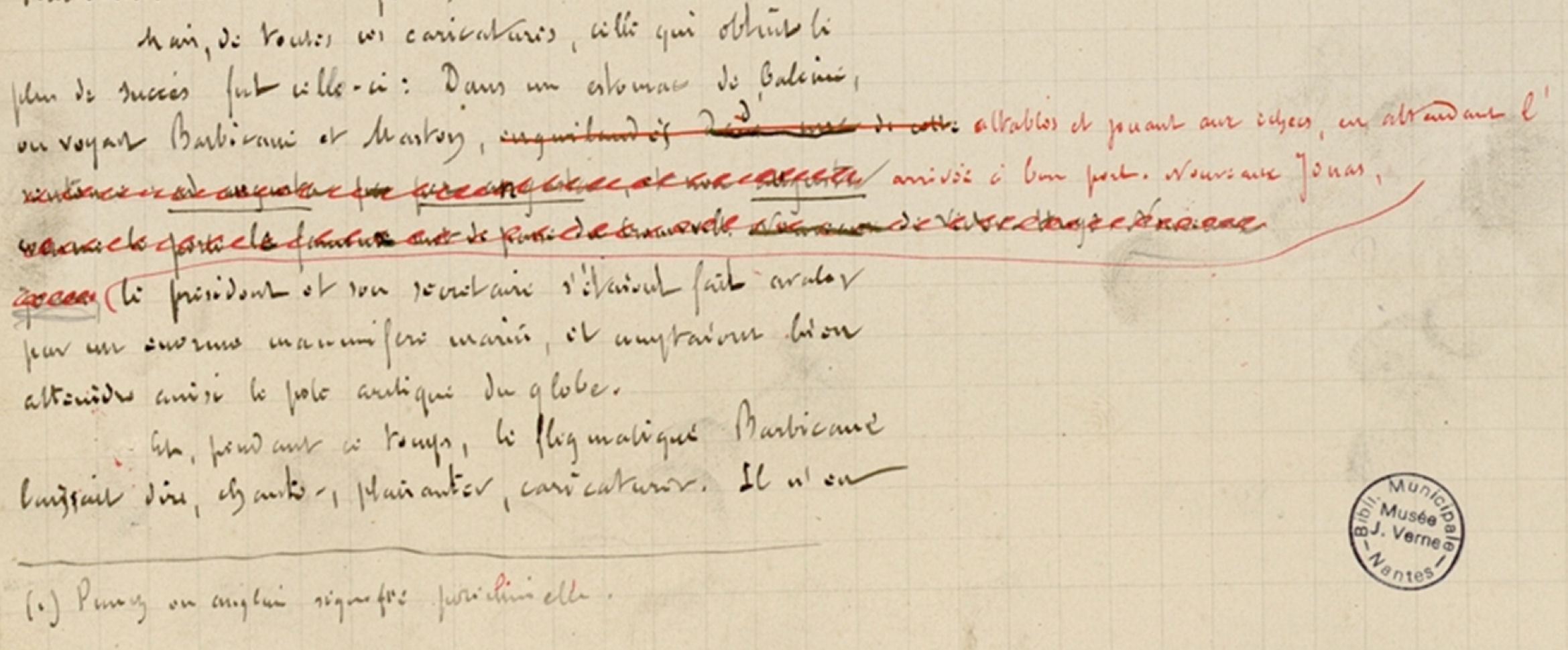

They differ appreciably from the manuscript version preserved in the collection of the Bibliothèque municipale de Nantes [46]. The published text is longer than the manuscript version by about 20%; the additions include the mentions of Punch, La Lanterne magique, Le Charivari, and Stop, as well as several small details concerning the individual caricatures. In one paragraph of the manuscript version, lines have been struck through and marginal corrections inserted in red ink. These emendations, which appear to be in Verne’s hand, introduce the phrase “Nouveaux Jonas” to the text (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Detail of the manuscript of the “Nouveaux Jonas” passage. Reproduced with the kind permission of Mme Agnès Marcetteau and the Bibliothèque municipale de Nantes.

The texts of the manuscript and édition originale versions of the passage are reproduced below, in alternating passages

labeled “MS” and “EO,” respectively. For the manuscript, struck through text is indicated thus; unreadable text appears as series of “xxx”; Verne’s marginal

corrections are enclosed in <angle brackets> [47].

MS: On voyait aussi J.T. Maston, non moins aussi viré que son chef par les caricaturistes.

EO: On « croquait » aussi, dans un numéro du Punch, journal anglais, J.-T. Maston, non moins visé que son chef par les caricaturistes.

MS: Un autre croquis figurait Impey Barbicane et les membres du Conseil d’administration de la Société, opérant au milieu des flammes, comme d’incombustibles salamandres.

EO: Un autre croquis, dans la Lanterne magique, de Bruxelles, représentait Impey Barbicane et les membres du Conseil d’administration de la Société, opérant au milieu des flammes, comme autant d’incombustibles salamandres.

MS: Pour fondre les glaces de l’océan Paléocrystique, n’avaient-ils pas eu l’idée de répandre à sa surface toute une mer d’alcool, et de l’enflammer — ce qui convertissait le bassin polaire en un immense bol de punch ? Et, jouant sur ce mot punch, le dessinateur n’avait-il pas poussé l’irrévérence jusqu’à faire de Barbicane un ridicule polichinelle.

EO: Pour fondre les glaces de l’océan Paléocrystique, n’avaient-ils pas eu l’idée de répandre à sa surface toute une mer d’alcool, puis d’enflammer cette mer — ce qui convertissait le bassin polaire en un immense bol de punch ? Et, jouant sur ce mot punch, le dessinateur belge n’avait-il pas poussé l’irrévérence jusqu’à représenter le président du Gun-Club sous la figure d’un ridicule polichinelle.

MS: Mais, de toutes ces caricatures, celle qui obtint le plus de succès fut celle-ci: Dans un estomac de baleine, on voyait Barbicane et

Maston, enguirlandés dans d’une de cette sorte de angulée et une angantée, et non allgenté xxxx la porte la fenêtre sur de partie du brannurcle s’étaient de

vitre ttxgée Vxxxxxx xxxxx <attablés et jouant aux échecs, en attendant l’arrivée à bon port. Nouveaux Jonas,> le président et son secrétaire s’étaient fait

avaler par un énorme mammifère marin, et comptaient bien atteindre ainsi le pole arctique du globe.

EO: Mais, de toutes ces caricatures, celle qui obtint le plus de succès fut publiée par le journal français Charivari sous la signature du dessinateur Stop. Dans un estomac de baleine, confortablement meublé et capitonné, Impey Barbicane et J.-T. Maston, attablés, jouaient aux échecs, en attendant leur arrivée à bon bort. Nouveaux Jonas, le président et son secrétaire n’avaient pas hésité à se faire avaler par un énorme mammifère marin, et c’était par ce nouveau mode de locomotion, après avoir passé sous les banquises, qu’ils comptaient atteindre l’inaccessible Pôle du globe.

Appendix B — “La Presse aux États-Unis”

The full text of Part 1 of Max O’Rell’s essay is reproduced below [48]. Paragraph breaks, punctuation, and italicized text are as in the original. The portion of the essay that appears below the Stop caricature in Sans dessus dessous (Figure 1) is shown in bold type.

———

LA PRESSE AUX ÉTATS-UNIS

En découvrant l’Amérique, Cristophe Colomb a fourni au vieux monde une source inépuisable d’inventions divertissantes. Vous passez du curieux au merveilleux, du merveilleux à l’incroyable, de l’incroyable à l’impossible.

C’est au journalisme américain, toutefois, qu’il faut donner la palme : c’est le dernier mot de la fantasmagorie.

Prenons les journaux de la semaine : huit, dix et douze pages, et des pages à huit et neuf colonnes, imprimées en caractères fins, le tout pour la somme de deux ou trois sous. Voilà pour la quantité.

Ce qui attirera tout d’abord votre attention, c’est le titre des articles. Les moindres entrefilets ne sauront vous échapper, grâce à ces merveilleux en-têtes. C’est un génie spécial qu’il faut pour imaginer de pareils tire-l’œil.

En voici quelques-uns que j’ai recueillis à New-York et à Chicago.

La mort de madame Garfield, mère du feu président, est annoncée avec l’en-tête :

Mort de grand’maman Garfield.

Le mariage de M. Maurice Bernhardt :

Le garçon à Sarah mène sa fiancée à l’autel.

L’exécution d’un criminel est annoncée ainsi par un journal de Chicago :

Un assassin expédié à Jésus (jerked to Jesus).

Deux comptes rendus de la cour du divorce à Chicago sont intitulés respectivement :

Fatiguée de William.

Madame Carier trouve que son mari

ne l’embrasse pas gentiment.

Le jeune comte de Cairns avait été fiancé à plusieurs jeunes filles. La nouvelle de son mariage est annoncée aux Américains, ou plutôt aux Américaines, de la façon suivante :

Enfin Cairns est pincé.

M. Arthur Balfour, ministre d’Irlande, ayant refusé de répondre à des attaques du parti national irlandais, un grand journal de New-York annonce ainsi la chose :

Balfours s’en f... comme de l’an quarante.

M. Joseph Chamberlain, envoyé extraordinaire du gouvernement de Sa Majesté Britannique, avait été invité à un banquet par les membres d’un cercle de New-York. Au dernier moment, l’honorable gentleman, retenu par des affaires d’État à Washington, dut s’excuser. Le lendemain je lisais dans le New-York Herald :

Un dîner de moins pour Joe.

Pendant mon séjour aux États-Unis, les journaux s’occupaient beaucoup d’un certain financier, nommé Jacob Sharp. Accusé de banqueroute, ce financier avait été arrêté, puis relâché, et la presse de grogner et de s’écrier, assez spirituellement du reste, que tous les Américains avaient leurs trials excepté les financiers.

Or, un beau jour, les journaux durent se taire : le pauvre Jacob venait de passer de vie à trépas.

Ce jour-là même, je rencontrai le rédacteur en chef d’un des grands journaux quotidiens.

— Eh bien, lui dis-je, voilà une belle occasion pour un fameux en-tète demain matin ; vous n’allez pas la manquer, j’espère ?

— Que voulez-vous dire?

— Comment! vous me le demandez ? Jacob parti au sommet de l’échelle, parbleu !

— C’est une idée sublime. Je prends l’en-tête, combien voulez-vous?

— Rien du tout, je vous en fais cadeau.

La mort du financier, racontée en deux colonnes, paraissait le lendemain, intitulée :

Jacob parti au sommet de l’échelle

Si jamais je me propose de devenir journaliste en Amérique, ce haut fait sera le plus beau titre que je puisse faire valoir auprès de mon futur rédacteur en chef.

Le journalisme américain est avant tout un journalisme à sensation. Si les faits rapportés sont exacts, tant mieux pour le journal ; sinon, tant pis pour les faits. Figurez-vous un pays jonché de Pall Mail Gazettes, contenant des articles signés, non pas par « celui qui connaît les faits », mais souvent par « celui qui ne les connaît pas ».

Pour réussir comme journaliste, il ne s’agit pas d’être homme de lettres et de savoir faire l’article de fond à la John Lemoinne, à la Henri Fouquier ; il faut intéresser et amuser le lecteur coûte que coûte.

Les comptes rendus de cour d’assises et de police correctionnelle éclipsent les romans de Gaboriau et de M. du Boisgobey. Moi qui ne lis jamais les comptes rendus de tribunaux dans les journaux anglais, je me suis plus d’une fois surpris, en Amérique, enchaîné au récit d’un meurtre, suivant les débats de l’affaire, incapable d’en perdre un mot. Tour à tour ému, frappé d’horreur, j’allais jusqu’au bout ; puis, me passant la main sur le front, je me disais : « Que tu es bête, cela n’est pas arrivé ! »

Le journaliste américain doit être piquant, pimpant, brillant. Il faut qu’il sache, non pas rapporter, mais raconter un incendie, un accident, un procès, et au besoin tirer parti de l’incident le plus insignifiant et en faire une ou deux colonnes intéressantes, readable, comme disent les Anglais avec raison. Il faut aussi qu’il ait constamment l’œil ouvert, l’oreille au guet et le nez au vent, car, avant tout et surtout, il faut qu’il arrive premier dans cette course à la nouvelle; s’il lui arrive de se laisser devancer par un confrère, il est flambé.

Mais, allez-vous vous écrier, que voulez-vous que le malheureux puisse faire quand il n’y a pas de nouvelles? Que faire? Eh bien, et l’imagination, cela ne compte-t-il donc pour rien ? Voici comment un journaliste américain devint célèbre ; on est encore fier à Chicago de raconter la chose.

Un journaliste se promenait un soir dans un des quartiers retirés de la ville, — à la recherche de quelle aventure, l’histoire ne le dit point. Tout à coup, une forme humaine, couchée immobile sur le trottoir, attire les regards de notre héros. Le journaliste s’approche, se baisse : c’est un cadavre qu’il a devant lui. La première idée qui lui passe par la tète est d’aller immédiatement prévenir le commissaire de police.

La seconde idée est pratique, et il l’adopte. La voici. Son journal paraît le soir à deux heures. Or, s’il court à l’instant chez le commissaire de police, l’affaire va s’ébruiter et fournir à la gent reporter une ou deux colonnes pour les journaux du lendemain matin. C’est une trouvaille que ce cadavre, et quand on en fait une pareille on la garde pour soi. Que faire? C’est bien simple. Notre journaliste traîne le cadavre dans une masure inoccupée et le cache soigneusement. A onze heures, le lendemain matin, il le découvre par hasard, va au plus vite faire sa déclaration au commissaire de police, et court au journal muni des deux colonnes préparées la veille. A deux heures, le journal fait crier par la ville : « Assassinat mystérieux à Chicago, découverte de la victime par un des rédacteurs ! »

Les journaux du matin étaient refaits, et les confrères du soir étaient enfoncés.

Les crime, les divorces, les enlèvements, les mésalliances, les potins de toutes sortes fournissent aux journaux les trois quarts de la matière. Une affaire mystérieuse fait la fortune d’un journal. Voici, comme exemple, une jolie histoire de mésalliance.

Pendant des semaines entières, les journaux américains s’occupèrent d’une jeune fille, appartenant à la haute société de Washington, qui, paraît-il, s’était fiancée à un Indien, nommé Chaska, un Indien de la plus belle eau, de la tribu des Sioux. Descriptions du farouche sauvage, des fêtes qui allaient se célébrer en son honneur au camp du grand chef, Oiseau Rapide, des ornements mirifiques dont allaient s’orner les membres de la tribu, rien n’y manquait. Désespoir d’une famille, menaces d’un père indigné, larmes d’une mère affligée, rien, paraît-il toujours, ne touchait le cœur de la belle aventurière, excepté les yeux perçants de Chaska.

Enfin le mariage a lieu, non seulement au grand jour, mais à l’église. Ce n’est pas Oiseau Rapide qui bénit les jeunes époux, c’est le ministre de la paroisse. Le roman fait place à la vérité, et, sans se déconcerter le moins du monde, les journaux annoncent, en quelques lignes seulement cette fois, que la demoiselle vient d’épouser un employé au bureau des « Affaires Indiennes ».

(La fin à demain.)

Max O’Rell.

Works cited

- Altick, Richard D. Punch: The Lively Youth of a British Institution, 1841–1851. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1997.

- Badoureau, Albert. Le Titan moderne: Notes et observations remises à Jules Verne pour la rédaction de son roman Sans dessus dessous. Eds. Colette Le Lay and Olivier Sauzereau. Nantes: Actes Sud, 2005.

- Barthes, Roland. “L’Effet de Réel.” Communications 11 (1968): 84–89.

- ———. “The Reality Effect.” The Rustle of Language. Trans. Howard, Richard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1986. 141–48.

- Bénézit, Emmanuel. Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs. Nouv. éd. Ed. Jacques Busse. 14 vols. Paris: Gründ, 1999.

- Brunschwig, Chantal, Louis-Jean Calvet, and Jean-Claude Klein. 100 Ans de chanson française. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1972.

- Butcher, William. Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2006.

- Childs, Elizabeth C. “The Body Impolitic: Press Censorship and the Caricature of Honoré Daumier.” Making the News: Modernity & the Mass Press in Nineteenth-Century France. Eds. Dean De la Motte and Jeannene Przyblyski. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999. 43–81.

- Clause, Nadine-Emmanuel. “Louis Pierre Gabriel Bernard Morel-Retz dit Stop (pseud.) 1825–1899.” http://nadine-emmanuel.clause.pagesperso-orange.fr/famille/stop/index.html. Accessed July 30, 2015.

- Dayez, Anne, Michel Hoog, and Charles S. Moffett. Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1974.

- Dehs, Volker. “La Publication pré-originale de ‘Sans dessus dessous’.” Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne (NS) 88 (1988): 40.

- Delvau, Alfred. Histoire anecdotique des cafés & cabarets de Paris, avec dessins et eaux-fortes de Gustave Courbet, Léopold Flameng et Félicien Rops. Paris: E. Dentu, 1862.

- Dixmier, Michel, Annie Duprat, Jean-Marie Génard, Bruno Guignard, Claude Robinot, Bertrand Tillier, and Jean-Noël Jeanneney. Quand le crayon attaque. Images satiriques et opinion publique en France 1814–1918. Paris: Éditions Autrement, 2007.

- Evans, Arthur B. “The Illustrators of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires.” Science Fiction Studies 25.2 (1998): 241–70.

- Figures contemporaines tirées de l’Album Mariani. Vol. 7. Paris: Librairie Henry Floury, 1902.

- Goldstein, Robert Justin. “Censorship of Caricature and the Theater in Nineteenth-Century France: An Overview.” Yale French Studies 122 (2012): 14–36.

- ———. Censorship of Political Caricature in Nineteenth-Century France. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989.

- ———. Political Censorship of the Arts and the Press in Nineteenth-Century France. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

- Gondolo della Riva, Piero, ed. Bibliographie analytique de toutes les œuvres de Jules Verne. I: Œuvres romanesques publiées. Paris: Société Jules Verne, 1977.

- Gonzalez-Quijano, Lola. “« La chère et la chair » : Gastronomie et prostitution dans les grands restaurants des boulevards au XIXe siècle.” Genre, sexualité & société 10 (2013). http://gss.revues.org/2925. Accessed July 30, 2015.

- Gretton, Thomas. “European Illustrated Weekly Magazines, c. 1850–1900. A Model and a Counter-Model for the Work of José Guadalupe Posada.” Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 70 (1997): 99–125.

- Harpold, Terry. “Picturing Readers and Reading in the Illustrated Voyages extraordinaires.” Collectionner l’Extraordinaire, sonder l’Ailleurs. Essais sur Jules Verne en hommage à Jean-Michel Margot. Eds. Terry Harpold, Daniel Compère, and Volker Dehs. Amiens: Encrage Edition / L’Association des Amis du Roman Populaire, 2015. 107–32.

- Kerr, David S. Caricature and French Political Culture, 1830–1848: Charles Philipon and the Illustrated Press. Oxford University Press: New York, 2000.

- Le Men, Ségolène. “La Recherche sur la caricature du XIXe siècle: état des lieux.” Perspective 3 (2009). http://perspective.revues.org/1332. Accessed July 30, 2015

- Margot, Jean-Michel, ed. Jules Verne en son temps. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2004.

- Martin, Charles-Noël. La Vie et l’œuvre de Jules Verne. Paris: Michel de l’Ormeraie, 1978.

- O’Rell, Max [pseud. Léon Paul Blouet], “La Presse aux États-Unis [1er partie],” Le Charivari January 28, 1889: 2–3.

- ———. “La Presse aux États-Unis [2e partie],” Le Charivari January 29, 1889: 2–3

- O’Rell, Max [pseud. Léon Paul Blouet] and Jack Allyn. Jonathan et son continent: La Société américaine. 9e éd. Paris: Calmann Lévy, Éditeur, 1889.

- Pinson, Guillaume. L’Imaginaire médiatique. Histoire et fiction du journal au XIXe siècle. Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2012.

- Portalis, Roger and Henri Béraldi. Les Graveurs du XIXe siècle. Guide de l’amateur d’estampes modernes. 12 vols. Paris: Librairie L. Conquet, 1885–92.

- Raymond, François. “Postface.” In Jules Verne, Sans dessus dessous. Grenoble: Éditions Jacques Glénat, 1976. 197–90.

- Tillier, Bertrand. La Républicature. La Caricature en France, 1870–1914. Paris: CNRS Éditions, 1997.

- Vapereau, Gustave. Dictionnaire universel des contemporains. Paris: Hachette, 1893.

- Verhoeven, Jana. Jovial Bigotry: Max O’Rell and the Debate over Manners and Morals in 19th Century France, Britain and the United States. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2012.

- Verne, Jules. Salon de 1857. Édition établie, présentee et annotée par William Butcher. Acadien, 2008.

- ———. Salon de 1857. Texte intégral établi, présenté et annoté par Volker Dehs. N.p., 2008.

- ———. Sans dessus dessous. Paris: Hetzel et Cie, 1889. (In-18 edition.)

- ———. Sans dessus dessous. Illus. George Roux. Paris: Hetzel et Cie, 1889. (Gr. in-8° edition, “simple” vol.)

- ———. Sans dessus dessous / Le Chemin de France / Gil Braltar. Illus. George Roux. Paris: Hetzel et Cie, 1889. (Gr. in-8° edition, “double” vol.)

- Verne, Jules, Michel Verne, and Louis-Jules Hetzel. Correspondance inédite de Jules et Michel Verne avec l’éditeur Louis-Jules Hetzel (1886–1914). Tome I: 1886–1896. Eds. Olivier Dumas, Volker Dehs, and Piero Gondolo della Riva. Geneva: Éditions Slatkine, 2004.

- Williams, Orlo. Vie de bohème. A Patch of Romantic Paris. Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1913.

Notes

- Punch en anglais signifie polichinelle (Footnote in the original). ^

- Image source: Bibliothèque nationale de France, ark:/12148/bpt6k6514209b. ^

- In Harpold 2015 I count 35 such images. ^

- The gr. in-8° edition of Sans dessus dessous includes illustrations of both types. In ch. I, Evangélina Scorbitt is shown reading from the New York Herald, presumably the issue including the “Avis aux habitants du globe terrestre” by the North Polar Practical Association, announcing their claim on the Pole. In ch. V, Donellan and Toodrink are shown seated in the Two Friends tavern, discussing the prospects of finding coal at the North Pole. In the background, an unidentified man is reading a newspaper. Perhaps he is reading from the current issue of… Le Charivari ? ^

- Image source: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Common license CC-BY-SA 3.0. The complete January 28, 1889 issue, including the detail shown in Figure 4, is available online, at: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/charivari1889. ^

- Michelet’s first name, or if this is a pseudonym, is unknown. Gallica includes 60 examples of his work during the 1880s and 1890s, chiefly for the journal Scènes théâtrales (including an engraving of scenes from the Théâtre de la Gaîté’s ill-fated 1883 production of Verne’s Kéraban-le-têtu), and several illustrations by Stop. ^

- The dimensions of the Charivari page, including margins, are 295 × 420 mm. Those of the Sans dessus dessous page are 175 × 270 mm. The apparent dimensions of the embedded page are approximately 125 × 205 mm. ^

- La Caricature morale, religieuse, littéraire et scénique, published between 1830 and 1843. This is not the similarly-named La Caricature, founded by Albert Robida and published between 1880 and 1904. ^

- Véron had become editor of Journal amusant in 1874. Successor to Le Journal pour rire, founded by Philipon in 1848, Le Journal amusant was one of two satirical magazines spun out of Journal pour rire when it was ended in 1851. (The second was Le Petit Journal pour rire, initially edited by Nadar.) Le Journal amusant continued to be published after Véron’s retirement in 1899. After an interruption during the First World War, the journal resumed publication, ending in 1933. ^

- The fortunes of political caricature in 19th century France, and the roles played by La Caricature, Le Charivari, Aubert, Philipon, and artists such as Daumier, Gill, and Grandville, are subjects too complex and far-reaching to be properly addressed in this essay. The critical literature on French caricature has increased explosively in recent years and I will not attempt to summarize it. (Le Men’s 2009 survey, although dated, gives an excellent sense of the field’s scope and diversity.) Goldstein’s recent article (2012) and the essays by the other scholars included in that issue of Yale French Studies are good short introductions. Goldstein’s 1989 study remains the best long treatment in English of censorship of the arts and the press throughout Europe in the 19th century (Political Censorship) and the special case of caricature in France (Political Caricature). Also valuable are Kerr (2000), Dixmier, et al. (2007), and Tillier (1997). Childs’ (1999) essay on Daumier, Philipon, and Le Charivari is an excellent overview of the journal’s early decades. My summary of Le Charivari’s history draws primarily on Childs and on Goldstein’s contributions (Political Caricature, “Censorship of Caricature”). ^

- “The French police minister made his understanding of this point clear in an 1852 directive to his subordinates in which he declared that… ‘the worst page of a bad book requires some time to think and a certain degree of intelligence to understand, while the drawing communicates with movement and life, as to thus present spontaneously, in a translation which everyone can understand, the most dangerous of all seductions, that of example’” (Goldstein 2012, 25–26). ^

- Dixmier’s contribution to Dixmier, et al. (2007) is particularly strong on this period. ^

- Cf. Gill’s caricature of Verne for the cover of L’Éclipse, (December 13, 1874), showing the author turning the crank of a barrel organ in the shape of the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin. The theater was at the time the venue of Verne and Dennery’s stage production of Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours. ^

- Most (in)famously, Daumier’s drawings of Louis-Philippe’s head transforming into, or merely figured as, a swollen pear. These appeared first in La Caricature, and the best-known versions appeared in Le Charivari. ^

- The political mood of Le Charivari, however — like most of the satirical French publications of the period — remained strongly Republican and nationalist. Over time, particularly after the turn of the century and up until it ceased publication in 1937, the journal’s politics drifted towards the extreme right. ^

- “L’EXAMEN DES COCHERS – Et si vous écrasiez un passant? – Ça me laisserait froid ; nous sommes assurés.” ^

- “Draner” = “Renard” à l’inverse. My summary of Draner’s career is based primarily on Bénézit 1999 (4: 724) and Tillier 1997. ^

- For examples see Gallica’s archive of works by Draner, http://data.bnf.fr/13623598/draner/. ^

- My summary of Morel-Retz’s career is based primarily on Bénézit 1999 (9: 836), Clause 2015 and Vapereau 1893. ^

- Morel-Retz presented at least one work at the 1857 Salon de Paris, but he is not among the artists mentioned in Verne’s long article on the Salon. Cf. Verne/Butcher 2008; Verne/Dehs 2008. ^

- For examples of his work, see Gallica's archive of works by Stop, http://data.bnf.fr/12435404/stop/. ^

- Cf. Margot 2004. I am indebted to Volker Dehs for his help in locating this portrait of Blouet. ^

- My summary of Blouet’s career is based primarily on Verhoeven 2012. ^

- Sales of Blouet’s books during this period substantially exceeded the sales of new titles in Verne’s Voyages extraordinaires (cf. Martin, Annexe II). ^

- See Pinson’s discussion of the figure of the journalist in Verne, especially the character’s movement onto, off, and onto again the central stage of the narrative, or his isolation from and return to society, as signs of a programmed “remédiatisation” of fictional discourse. (“Les romans de Verne appartiennent à un âge médiatique évolué: ses robinsonnades ne sont pas la reprise innocente d’un motif intemporel mais bien au contraire sa réactivation à l’ère de l’information” [202]). ^

- Though, as Verhoeven points out (179–82), O’Rell and Twain did not always practice as they preached. In contrast to his public defenses of male-dominated households, and anti-feminist and anti-suffragist positions, O’Rell’s married life appears to have been progressive and accepting of his wife’s independence. Twain’s defense of women’s self-determination are contradicted somewhat by the conventional Victorian, “angel in the house,” roles of his wife and daughters. ^

- See Appendix B for the full text of Part 1. ^

- Jonathan was among the most commercially successful of Blouet’s later books, selling as many as 190,000 copies in the U.S, England, and France (Verhoeven 194). ^

- In 1873, Claude Monet painted two versions of Boulevard des Capucines, Paris from the vantage of Nadar’s studio, high above the street. (The painting is of the view toward Opéra, away from Hill’s Tavern.) Boulevard des Capucines, Paris was among the paintings included in the first Impressionist exhibition in April 1874, also in Nadar’s studio. It was one of two paintings by Monet in the exhibition that were subjected to special derision in a review by Le Charivari’s art critic Louis Leroy, in the April 25, 1874 issue (“L’Exposition des impressionists,” 79–90). The review is widely credited with giving the new artistic movement its name. (Dayez 1974, 159–63.). ^

- Volker Dehs reports that the correspondence between Roux and Hetzel père and fils archived in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (NAF 16987, f° 291–99) includes no documents relating to Verne. (Personal correspondence, December 10, 2015.) ^

- All citations of the correspondence are from Verne et al. 2004 (Correspondance inédite), hereafter CI. ^

- On the Verne-Badoureau collaboration, see Badoureau 2005. ^

- CI 95–98. Hetzel’s principal objections are that important secondary characters are thinly drawn, that the novel too much resembles André Laurie’s 1887 Les Exilés de la Terre, and that the adventure is too detached from events of the previous Gun Club novels. ^

- It is clear throughout this correspondence that Verne is keen on getting technical details of the novel right, especially the mathematics of Badoureau’s supplemental chapter. “Jamais je n’aurai tant trimé sur un bouquin, jamais je n’aurai fait un tel travail de révision. Mais il le fallait, et j’espère qu’on ne pourra pas y relever une erreur” (CI 102). ^

- A small number of Roux’s plates, charcoal drawings, and wash drawings executed for Hetzel et Cie are preserved in the sous-fonds Hetzel in the Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC), housed in the Abbaye d’Ardenne, Saint-Germain la Blanche Herbe, France. A future phase of this project will involve a review of these materials, which may include evidence of the Stop caricature’s composition. ^

- Victor Petit? (See Portalis and Béraldi 1885–92, vol. X, p. 265.) This is the only illustration in the novel engraved by Petit, who seems to have worked on the Voyages extraordinaires only briefly, between 1888–1889 (Evans 1998). ^

- Gretton (1997) reports that by the mid-1860s, Le Charivari was printed entirely on relief presses, using a process called gillotage (zincography) to convert lithographs into relief surfaces (105), which would have then been combined with composed text to form the entire page. This is how Draner’s original comic would have been incorporated into the newspaper page. ^

- It cannot be known if any readers of Verne’s novel (that is, apart from those who were party to the production of the Stop caricature) recognized the precise source of the illustration’s framing elements, viz., the January 28, 1889 issue of the newspaper. But many readers would have recognized Le Charivari’s “Actualités” page and the O’Rell fragment as the sort of text that would appear on that page. ^