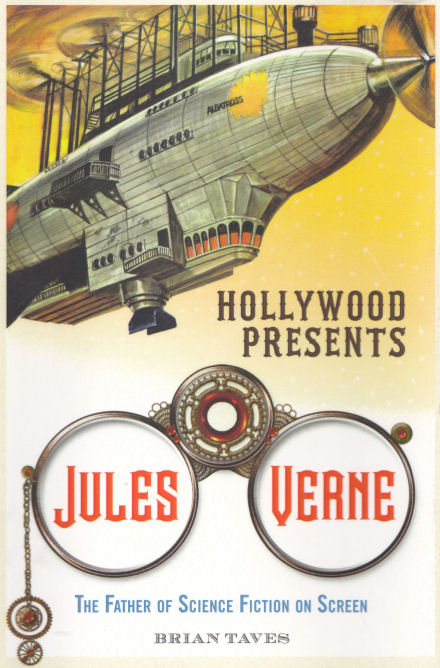

Readers of Verniana are familiar with Brian Taves, the specialist (recognized worldwide as such) of films inspired by Verne. A librarian at the Library of Congress, he has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Southern California and has already published six books on film. His seventh, for which Jules Verne specialists have been waiting for years, finally came off the presses in April 2015 [1].

It is not only an extension of “Hollywood's Jules Verne,” published in 1996 as Chapter 9 of The Jules Verne Encyclopedia [2], but a totally new work. Taves has written many other articles and chapters about movies of all kinds derived from the work of Jules Verne. This 358-page book is a comprehensive, academic-level, well-documented history of movies inspired by Verne’s works in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Intended for all kinds of readers, including some who may be unaware that Verne was a French writer, Taves begins his book with an introduction recalling the literary figure of Verne and the mutilation his works suffered through incomplete translations, in which the original text was sometimes profoundly altered. The subject of bad and sometimes criminal Anglo-Saxon translations of Verne has been covered in detail by Walter James Miller in the prefaces and comments of his various translations of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and in articles in Verniana and Extraordinary Voyages (newsletter of the North American Jules Verne Society) [3].

Brian Taves had the choice to tell the history of Hollywood movies devoted to Verne in one of two ways, either by following the chronology of Verne’s fiction and the movies inspired by these texts, or by following the chronology of the films themselves. He chose the second approach, because this allowed him to present how Verne was treated by the world of Hollywood film in the context of the modes and techniques in the history of cinema.

Taves' book covers not only film but also television broadcasts, all of what are called “moving images” (moving images is the name of the department where he works at the Library of Congress). So readers will also find mentions in his book of TV series and cartoons.

After the introduction devoted to explaining his methods, Taves begins with silent films (with a passing nod to Georges Méliès and Michel Verne), which he sees as an extension of the pièces à grand spectacle on stage during the last decades of the 19th century in the United States. The book reads like a novel, and is enhanced with 249 detailed notes, a selected bibliography and an index. The reader learns why the first silent Vernian film that Hollywood produced was Michael Strogoff in 1914, followed by After Five (based on The Tribulations of a Chinese in China) in 1915. 1916 sees the first Hollywood version of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, a milestone in the history of cinema, still available on DVD. And in 1922-1923, twelve episodes bring to the screen in serial form Around the World in Eighty Days, which Taves connects to Albert Robida’s Saturnin Farandoul, Nellie Bly’s 1898 travels around the world to beat Fogg’s record (then still alive in peoples’ memories), and the London musical Phileade Round in Fifty.

The first talking films came out in 1927. The next chapter, “Searching for a Popular Approach,” extends until 1945. In the wake of the success of 1916’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Williamson released The Mysterious Island in 1929, with the first Captain Nemo to speak, although most of the film was still silent. This is also the time when Adolf Wohlbrück became Anton Walbrook and played in a new Michael Strogoff movie, The Soldier and the Lady [4]. The name of Jules Verne was becoming more and more popular thanks not only to the movies but also to publication of the first biographies in English and the creation of the first Jules Verne Society in the United States [5].

The next ten years saw a new mysterious island with a background of interplanetary conflict (Mysterious Island, 1951) and two new Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the first in 1952 (with Leslie Nielsen as Captain Farragut), and the second in 1954, as everyone knows, by Robert Fleischer with Kirk Douglas as Ned Land and James Mason as Nemo, produced by Disney. This latter production was filmed in the same locations used by Williamson almost forty years earlier. Brian Taves calls this period of 1946 to 1955 “Creating a Style,” which also means “establishing a standard.”

The next period, from 1956 to 1959, moves from the standard to the archetype: “Establishing a Mythos as the Verne Cycle Begins.” It is the triumph of Around the World in Eighty Days (1956) by Mike Todd, with David Niven using a balloon (which became a popular stereotype) to cross the Alps. The chapter contains images showing that Todd’s first cut had placed his world tour in our time: We see Niven and Cantinflas in the cabin of a modern aircraft [6].

Chapter 5 covers only three years, from 1960 to 1962, but the title designates it as a summit in the history of Anglo-Saxon Vernian cinema: “The Height of the Verne Cycle.” A simple list (not exhaustive) is enough to prove its accuracy: Master of the World (1961, with Vincent Price as Robur), The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (American version of Vynalez Zkazy by Karel Zeman, 1961), Mysterious Island (with special effects by Ray Harryhausen, 1961), Valley of the Dragons (inspired by Hector Servadac, 1961), Flight of the Lost Balloon (loosely adapted from Five Weeks in a Balloon, 1961), and In Search of the Castaways (another Disney film, based on The Children of Captain Grant, with Maurice Chevalier and Hayley Mills, 1962).

During the following period, from 1963 to 1971, “The Cycle Changes,” animated movies came out and film adapted to the fledgling medium of television. Besides the novels that had already been adapted to the big screen, such as Around the World in Eighty Days, there now appeared pastiches (The Three Stooges Go Around the World in a Daze, 1963), From Earth to the Moon (Those Fantastic Flying Fools, 1967), and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Captain Nemo and the Underwater City, 1970), New novels were brought to the screen, including Strange Holidays (based on Two Years Vacation, 1969), The Southern Star (1969), and The Lighthouse at the End of the World (1971).

Chapter 7, “Toward a New Aesthetic,” covers the years 1972 to 1979. It discusses the triumph of animated films, often chopped up into several episodes. We find repeatedly Nemo, Fogg, Harding (the American Cyrus Smith), Robur, Lidenbrock, and their associates in more or less faithful adaptations and more or less serious adventures.

The 1970s were followed by a period during which, by dint of repetition, the Hollywood Vernian cinema became a little exhausted. Under the title “The Wandering Trail,” this chapter extends from 1981 to 1993. It includes animation and productions primarily based on the two major Verne novels, Around the World in Eighty Days and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. A previously untouched novel also came out in the Hollywood Verne filmography—following the release of the 1960 Mexican film on American TV, Hollywood produced its own film inspired by The Jangada: Eight Hundred Leagues on the Amazon (1993).

Chapter 9 covers the four years from 1993 to the end of 1996: “The Revival.” Taves closely links this period to other recognitions taking place on the literary level in the Anglophone world. In the wake of popular and academic publications on Jules Verne (by Peter Costello, Peter Haining, Jean Chesneaux, Arthur B. Evans, Andrew Martin, and William Butcher) [7], and in connection with the development of audiobooks available on CD, Vernian cinema changed course. It now provided the public with documentaries on the life and works of Jules Verne, Around the World in 80 Days where the characters are animals, and capers in space with a descendant of Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues in Outer Space, better known as Space Strikers.

The title of the next chapter shows the evolution of the Hollywood Verne movies from 1997 to 1999: “Telefilms and Miniseries Reign.” Television becames more important, and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea enjoyed the lion's share of it. But novels such as Journey to the Center of the Earth, Children of Captain Grant, Robur the Conqueror, and The Aerial Village provided films, episodes, situations, and even just names in adventure films that had nothing to do with Jules Verne. As everything is interconnected, Brian Taves links masterfully to Verne works productions such as Star Wars or Crayola Kids that ostensibly have nothing to do with Verne novels.

During the first years of this century (2000-2003), Jules Verne himself became a Hollywood character: “Biography or Pastiche.” This penultimate chapter of the book got its title mainly from The Secret Adventures of Jules Verne, in which the popular archetype represented by the name of the novelist skyrocketed to heights dismaying any Vernian purist [8]. During the same period, the Alan Moore comic book was brought to the screen (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen) with, for the first time, an Indian actor playing the role of Nemo. There was also a new television biography produced by the BBC, The Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne (2003), which was relatively reliable and complete.

The following five years (2004 to 2008) are considered by Brian Taves to be “Dismal Reiterations.” The lack of imagination was felt in the productions of this period, whether with Jackie Chan in Around the World in 80 Days or Patrick Stewart interpreting Nemo in a 2005 TV movie inspired by The Mysterious Island. Twenty thousand not being enough, people could go to 30,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and a new biography (Prophets of Science Fiction) came out in 2006 that combined Verne and Wells, the former mainly depicted as an inspired prophet.

Finally, since 2008, there seems to have been an attempt at renewal due to technological developments applied to films in 3D. The two versions of travel to the center of the Earth (Journey to the Center of the Earth 3D and Journey 2: The Mysterious Island) allowed Brian Taves to conclude: “Together, the brilliant combination of Vernian elements offered by the two Journey movies in 2008 and 2012 demonstrated the original big-screen possibilities for the author in twenty-first century.”

Hollywood Presents Jules Verne would be perfectly at home in at least two types of libraries: that of any specialist and lover of Jules Verne, of course, but also that of any passionate fan of film history. With his depth of knowledge of the work and criticism of Verne, Brian Taves easily avoids the trap of sticking only to a listing of Vernian cinema. He constantly refers to novels and short stories brought to the screen, and as a result, we see the popular Jules Verne archetype develop through the production of the cult movies, such as the 1954 Disney Twenty Thousand Leagues, the 1956 Mike Todd Around the World, and many others, that influenced future productions. The book is a history, a story, and it reads like a novel.

Notes

- Arthur B. Evans - “Culminating a Decade of Scholarship on Jules Verne”. Science Fiction Studies, vol. 42, 2015, P. 557-565. ^

- Brian Taves & Stephen Michaluk, Jr. (dir.) - The Jules Verne Encyclopedia. Lanham (MD) & London, The Scarecrow Press, 1996, XVIII + 258 p. ^

- Walter James Miller - “The Rehabilitation of Jules Verne in America: From Boy’s Author to Adult’s Author, 1960-2003.” Extraordinary Voyages, vol. 10, no 2, December 2003, pp. 2-5; “As Verne Smiles.” Verniana, vol. 1, 2008-2009, pp. 1-8.; “The Role of Chance in Rehabilitating Jules Verne in America.” Extraordinary Voyages, vol. 17, no 1, December 2010, pp. 6-10. ^

- Philippe Burgaud – “Les avatars cinématographiques du Michel Strogoff de Joseph N. Ermolieff.” Verniana, vol. 7, 2014-2015, pp. 17-62. ^

- Jean-Michel Margot - “Histoire des études verniennes.” In Jules Verne, Literatura, ciencia e imaginación, Marratxi (Islas Baleares), Ediciones Paganel (Sociedad Hispánica Jules Verne), 2015, pp. 199-214. ^

- After Mike Todd passed away, his widow, Elizabeth Taylor, offered the 426 reels of Around the World in 80 Days to the Library of Congress. Brian Taves was charged with watching and inventorying them. He published the result of his research in three articles: “80 Days: Discoveries of a Unique Collection.” Library of Congress Information Bulletin, no 55, October 21, 1996, pp. 388-390; “La Collection E. Taylor à la Bibliothèque du Congrès ou Le Tour du monde en 80 jours à Washington.” Translated and annotated by Pierre Antifer. Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no 123, 1997, pp. 45-49; “80 Days: Discoveries of a Unique Collection.” Journal of Film Preservation, no 56, June 1998, pp. 18-22. ^

- The two following bibliographies give the necessary information about this period in Anglophone Vernian research: Jean-Michel Margot: Bibliographie documentaire sur Jules Verne. Amiens, Centre de Documentation Jules Verne, 1989, IV+344 p.; Volker Dehs: Bibliographischer Führer durch die Jules-Verne-Forschung – Guide bibliographique à travers la critique vernienne 1872-2001. Wetzlar: Förderkreis Phantastik, 2002, 438 p. ^

- Jean-Michel Margot - “Un Archétype populaire: Jules Verne.” Verniana, vol. 6, 2013-2014, pp. 81-92. ^