During the last two decades, the “Jules Verne rescue team” has produced a quantity of new translations, including many novels and plays that never appeared in English before to raise esteem of Verne in the Anglophone world. Still resonating from fifty years ago is a similar effort; although not equivalent in quality, it was even more prolific, reached a mass readership, and was the product of one person: “the Fitzroy edition of Jules Verne” by I.O. Evans. Evans turned out many volumes a year, without university presses, and his achievements left a legacy (for good and ill) that shaped mid-20th century Anglophone understanding of Verne. In the following pages, I examine the forces that shaped the Fitzroy series, and look at I.O. Evans the man and writer–who has been most accurately labeled (by the late Walter James Miller) as simultaneously Jules Verne’s best friend, and his worst enemy.

I.O. Evans (1894-1977)

I.O. Evans

Idrisyn Oliver Evans was born on November 11, 1894, in Bloemfontein, South Africa, and his family moved to England where he attended schools. [1] During “a childhood that was not over-happy,” Evans’s father had several of Verne’s best known titles in his collection, and they brought much delight to the admitted “bookworm.” [2] The only library within reach was that of the village church’s Sunday school, from which two volumes, one sacred, another secular, could be borrowed each week; A Journey to the Centre of the Earth seemed to have found its way there by accident. [3] “I borrowed it whenever it was available, read and re-read it, and almost got it by heart.” [4] He added, “later I progressed to Round the Moon, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, and other Verne masterpieces, as well as to H.G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe.” [5]

He soon read French, German, and Esperanto, explaining “whenever I wanted to ‘brush up my French’ the obvious thing was to read Verne in the original, and from my first visit to Paris I returned in triumph with a paperback edition of Voyage au centre de la terre.” [6] There were other, very different influences. “Even as a schoolboy, I was so transported by Omar Khayyam that I read him so often as to memorize most of his verses effortlessly; I could quote most of him now, though I have not read him for years! … Nevertheless I do not agree with his philosophy….” [7] Evans would author and privately publish verse throughout his life, including Sparks From a Wayside Fire, in 1954 to Peace and the Space Race, and Other Verses, in 1976.

He wrote, “training of body and mind, so as to make people healthy and thoughtful, is the real purpose of education.” [8] During his teenage years, from 1908, Evans was a pioneering member in the early days of the Boy Scouts and remained active in various youth movements, such as Kibbo Kift, the Woodcraft Kindred, where he was known by the nickname “Blue Swift.” He urged youth to try camping, athletics, learning a foreign language, and studying recent advances in science, especially theories of evolution.

College was not in his future, and he joined the Civil Service at age 18, in 1912. War intervened two years later, and he enlisted in the Army. He served with the Welsh Regiment and Special Brigade (Gas Companies), R.E., and was present at Vimy Ridge, Messines, Ypres, Dixmude, Fifth Army Retreat, and the Lys. He remained on the Western Front through the duration, finally demobilizing in 1919, and returned to the civil service. With Bernard Newman, he edited Anthology of Armageddon (1935), a mammoth volume that drew from 150 books from all sides and participants in World War I. Newman, like Evans, was also a distinguished veteran, and their book was hardly celebratory.

Faith was central to Evans’s life as well as his interpretations of history and literature. As early as 1932 he edited The Witness of History to the Power of Christ, a series of addresses to the Congregational Union of England and Wales. Toward the end of World War II Evans joined the Church of England, although he had respect for all religions. [9] In 1952 his composition, Led by the Star–A Christmas Play was published. Evans’s Christianity inspired much of his admiration for Verne, who he believed reflected his own religious beliefs.

In 1932, Evans authored The Junior Outline of History, an adaptation of the Wells adult history which he described as the most objective yet written, “a magnificent book by a very great man.” [10] Yet he also noted in that volume’s introduction, “Though Mr. Wells has given me permission to base this book on his Outline, I want to make it quite clear that he is not responsible for what I have written–indeed, I am not certain whether he will agree with it.” Consulting sources from James Henry Breasted to Philip Gibbs and Upton Sinclair, Evans lauded the increased equality between the sexes, and reconciliation between old foes of World War I that seemed to be established by the early 1930s. “World brotherhood begins at home and means tolerance and sympathy for those from whom we differ.” [11] He urged a new monetary system to end poverty, using science and the teachings of Christ.

His passion for science fiction was evident in a book of reference, The World of Tomorrow–A Junior Book of Forecasts (1933), about possible future inventions, partly illustrated with reproductions of artwork from science fiction magazines, and thus perhaps the first anthology of science fiction illustration. [12] By 1937, Evans was joining science fiction groups and had written an article for the July issue of Armchair Science. [13]

When he began to study geology, he “found its technical terms not forbidding but evocative; they were the sort of thing I’d seen in Verne.” [14] Evans became an amateur speleologist, authoring Geology by the Wayside in 1940 and The Observer's Book of British Geology in 1949. [15] He later became a member of several geological societies, and this gave him a special qualification when he had the occasion to translate Journey to the Centre of the Earth himself in 1961. Other volumes of his at this time took nature as their focus: Sea and Seashore (1948), Hidden Treasures (1948), Fossils (1949), and Fresh Water Described in Simple Language (1949).

Another hobby led him to write Cigarette Cards and How to Collect Them (1937), and with Newman he coauthored The Children's Own Book of the World–Impressions of the Countries of the World and the People Who Live in Them (1949). More historically–oriented volumes followed, with The Heavens Declare–A Story of Galileo (1949) and The Story of Early Times (1951). For a brief time Evans fond publishers willing to accept books of fiction and he authored several historical novels for juvenile reading, in which, as he explained, “appears a strong science-fictional interest … aptly described as ‘Henty crossed by Jules Verne’.” [16] He added, “I have tried to write from the point of view of prehistoric medicine-men sincerely and successfully practicising white or black magic; pious Hellenic polytheists; skeptical Alexandrian philosophers; and Renaissance Catholics–including Grand Inquisitors!” [17]

Evans Begins to Write About Verne

1955 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Jules Verne’s death, and lapsing copyrights helped to secure Verne’s place as interest in science fiction exploded with the dawn of the atomic age. Verne was becoming a source for the growing number of children’s editions of the great novels, including Classics Illustrated comic books, as well as a popular subject on radio and television, and Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea proved to be a major box-office hit in movie theaters.

Vernian scholarship was gaining a foothold, replacing the often wildly inaccurate newspaper and magazine accounts in his lifetime. The first book on Verne in English, the scholarly Jules Verne by Kenneth Allott, appeared in 1940, followed three years later by Jules Verne: The Biography of an Imagination, whose author, George H. Waltz, was an associate editor of Popular Mechanics. Both were indebted to Marguerite Allotte de la Fuye's unreliable 1928 biography, translated into English in 1954 as Jules Verne: Prophet of a New Age.

The time was ripe for a popularizer of Verne, and Sidgwick and Jackson, a publisher Evans had approached about an H.G. Wells anthology, was instead interested in such a volume of Verne. [18] Evans replied that Verne hadn’t written any short stories, although he later learned that this was not quite true. Discussion shifted toward quotations from the most exciting passages of Verne’s science fiction, with contextual notes and plot synopses, similar to Anthology of Armageddon.

Next began the process of finding Verne books themselves; they were not part of Evans’s library, and in a letter of the time, he mentions “financial stringency” as impairing his science fiction collecting. [19] Since Evans was executive officer in the Ministry of Works, much of his research was on Saturdays. Evans explained his purpose this way. “A writer who did so much to create an unprecedented development of a traditional art–form certainly cannot be ignored by the critics and the literary historians.” [20] Yet he found that “Verne's reputation rests nowadays almost completely on one or two favourite books, probably the only ones still in print; the others, being almost unobtainable, have most undeservedly been half forgotten”–and, he asserted, well repay reading. [21]

It was during the first year of his retirement, 1956, that Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction was published as a 236 page book, including excerpts from A Journey to the Center of the Earth, From the Earth to the Moon, Round the Moon, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Dropped From the Clouds, The Secret of the Island (the first and last volumes of L’Île mystérieuse), The Child of the Cavern (Les Indes noires), Hector Servadac, The Begum's Fortune, The Steam House, The Clipper of the Clouds (Robur-le-conquérant), The Floating Island (L’Île à hélice), For the Flag, An Antarctic Mystery (Le Sphinx des glaces), and Five Weeks in a Balloon. [22] Chapters were given such titles as “Thunderblast bomb” (For the Flag), “Behemoth mechanized,” (The Steam House), and in the acknowledgments Evans thanked his wife, Marie Elizabeth Mumford (whom he had married on March 6, 1937) for her “invaluable help not only in the detailed work of preparing the manuscript but in selecting passages likely to be of greatest interest.”

A brief interregnum followed, as Evans authored The Story of Our World in 1957, and Discovering the Heavens–a Junior History of Astronomy in 1958. Soon he undertook his ostensibly first-time Verne translations for Fantasy and Science Fiction (Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in England), in the July 1958 and November 1959 issues, with “Gil Braltar” followed by “Frritt-Flacc.” [23]

Shortly thereafter, Bernard Hanison decided to publish a new edition of Verne, and inquired at the major Verne collection of the Wandsworth Public Library, where Evans had researched Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction. [24] Hanison planned the first major series of Verne books issued in uniform binding since the last Sampson Low reprints of the 1920s, although a smaller scale issue had occurred from Didier at the beginning of the 1950s. There were two options, as Evans recalled. One was “an ‘authoritative’ edition including all that Verne wrote, or an abridged one adapted for a modern public ….”–consulting again the volumes he had used in his selections for Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction. [25] Applying his modern commercial judgment to the classics was also a project he had undertaken with an abridged version of Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur published in 1959.

Evans’s own diagnosis of the reason publishers had gradually stopped translating Verne was that in a decade that produced Wells’s The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, such novels as Clovis Dardentor and Mistress Branican paled by comparison–overlooking the fact that in the same decade Verne had also produced such up-to-the-minute science fiction as Carpathian Castle, The Floating Island, For the Flag, and An Antarctic Mystery, all of them appreciated by audiences of the day. [26] Evans did, however, correctly observe that such modern and appealing novels as The Village in the Treetops (Le Village aérien), The Golden Volcano, and The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission had been overlooked, and offered fresh translation possibilities.

The following series introduction appeared on the reverse of the dust jacket of the early volumes:

The intention of this new edition of one of the greatest of imaginative writers is to make it as comprehensive as possible, and to include his lesser-known, as well as his most popular works. Jules Verne is universally acclaimed as the founder of modern science fiction and as the author of a number of exciting stories of travel and adventure, but he also produced several historical novels and some acute studies of contemporary life.

The contract was signed in the publisher's offices were at 10 Fitzroy Street, London, hence naming it the Fitzroy Series. [27]

Evans’s outline to Hanison followed the pattern of the fifteen volume set Verne published by Vincent Parke and Company in 1911 as Works of Jules Verne, edited by Charles F. Horne. There were several parallels: Horne introduced each novel, although Evans’s prefaces would prove more thorough and scholarly; like Evans, Horne had used existing translations, save for the first appearance of Master of the World in English; and Horne edited the books to fit volumes of standard length. The Parke set contains 28 books, and a half-dozen short stories or novellas, while the Fitzroy series would ultimately include all that Horne had selected save for Dick Sands (Un Capitaine de quinze ans) and the non-fiction geographical tome, The Exploration of the World. [28]

The mixed results were evident from the first three volumes of the Fitzroy series, published in 1958. A Floating City was abridged from an inferior 1874 Sampson Low edition, when a better 1876 Routledge edition was also available. After The Begum's Fortune, Five Weeks in a Balloon was heavily abridged and paraphrased, containing only about two-thirds of the original. [29] Curiously, Evans did not use the 1876 Routledge translation of Five Weeks in a Balloon he had quoted in Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, so he was aware of the multiple existing translations.

Five Weeks in a Balloon — Associated Booksellers

Yet, at 253 pages, Five Weeks in a Balloon was one of the last volumes in the Fitzroy series with flexible length. Henceforth, only once did the books exceed about 190 pages, and while they could be a couple dozen pages shorter, the differences had to be made up in type font, margins, and chapter spacing, and the books had to be made to fit, regardless of their original length. [30]

Hence, the next year, 1959, while the lunar novels were given a new but poor translation in the traditional two volumes as From the Earth to the Moon and Round the Moon, Evans echoed the 1880 Sampson Low The Steam House with its two volume breakdown as The Demon of Cawnpore and Tigers and Traitors. The Mysterious Island, which had first appeared in three volumes as Dropped from the Clouds, The Abandoned, and The Secret of the Island, was now condensed into a two-volume work, splitting the initial half of The Abandoned into the first volume, and placing the second part at the beginning of The Secret of the Island.

Even more distressing, in 1959 Evans cut by nearly half the epic adventure Michael Strogoff, The Courier of the Czar, squeezing the book into a single volume that at least acknowledged “abridged edition” on its title page. Similarly, a year later he translated Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea into a single book of merely 192 pages, only half of the original.

Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, like Michael Strogoff and From the Earth to the Moon and Round the Moon, and Dropped from the Clouds and The Secret of the Island, did not credit Evans as editor or translator. Some of these had single frontispieces, plates chosen from among the original French engravings. Before the end of 1959, Hanison sold the rights to the Fitzroy edition to MacGibbon and Kee, who continued the series under the Arco Publications banner.

The Heyday of the Fitzroy Edition

Understandably, most of the initial retrospective attention on the Fitzroy series has turned to the dizzying array of retitlings and two volume works, rather than the business and impact of the series. However, instead of the traditional bibliographic or synchronic analysis, sufficiently established elsewhere, here I shall establish the chronological development of the series, and the selections Evans successively made among books and translations, as well as those he translated for the first time, to reveal his editorial judgments.

While retaining the uniform style of the volumes from the Bernard Hanison years, the Fitzroy series was evidently more cheaply produced, with lower quality paper, the plates deleted, and dust jackets that declined still further with the art of Jozef Gross. Verne illustrator Roger Leyonmark recalled them:

“My, how I hated those covers!… Economics must have dictated the use of only one color in tandem with black line art (three colors, if you consider how the white of the paper was utilized in each design)… Solid black line-work rules [and] the titles are printed in a bland, sans serif typeface devoid of any character, then dropped into the jacket with no apparent thought given to how the type might relate to the rest of the design. Layouts are typically broken up into deadly boring horizontal patterns (The Danube Pilot and The Traveling Circus are two unfortunate examples)…

And time and again, the artist throws away the exciting graphic possibilities of the story, settling upon an image scarcely hinting at the marvels it was supposed to visually suggest. A particularly inept example of this is 1965's Yesterday and Tomorrow.” [31]

The Associated Booksellers edition of Yesterday and Tomorrow, 1965

|

|

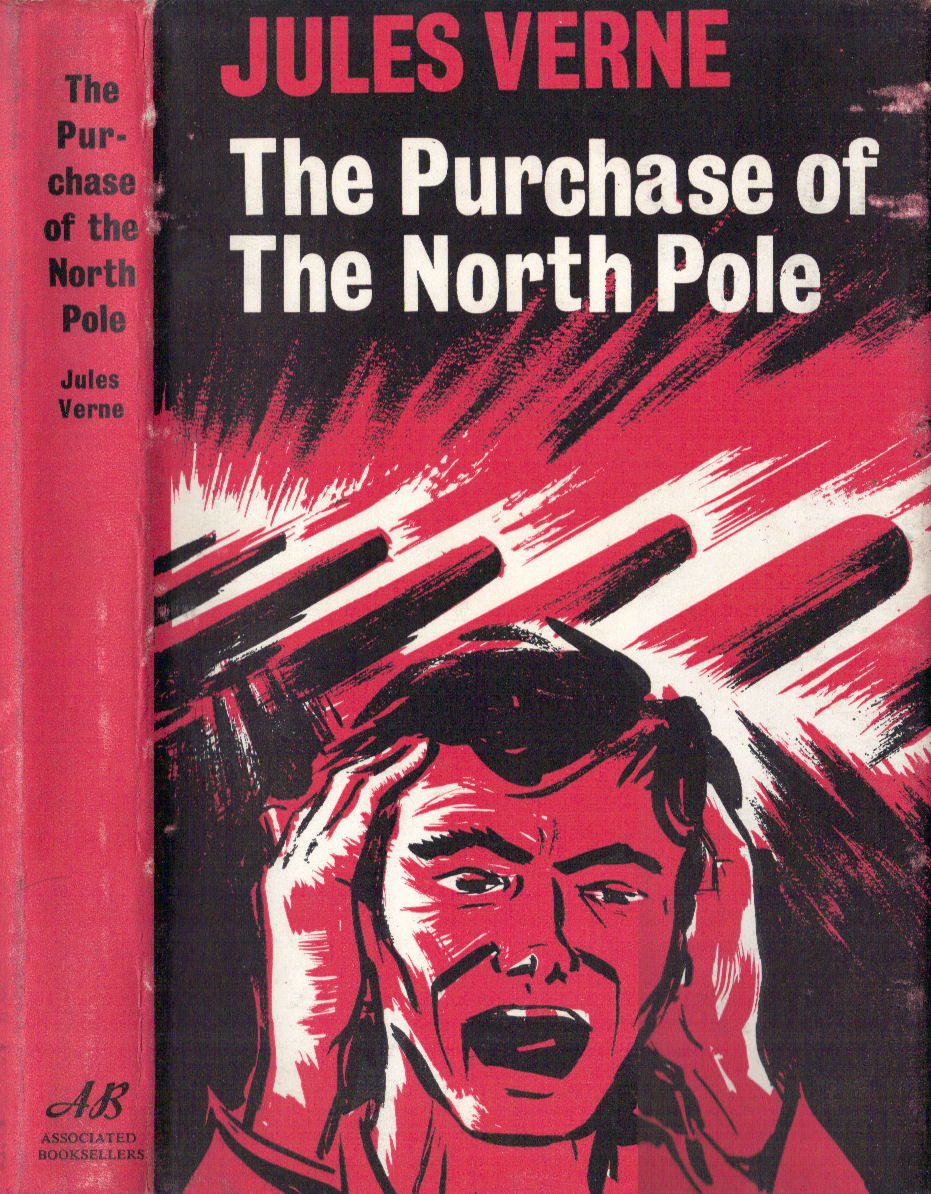

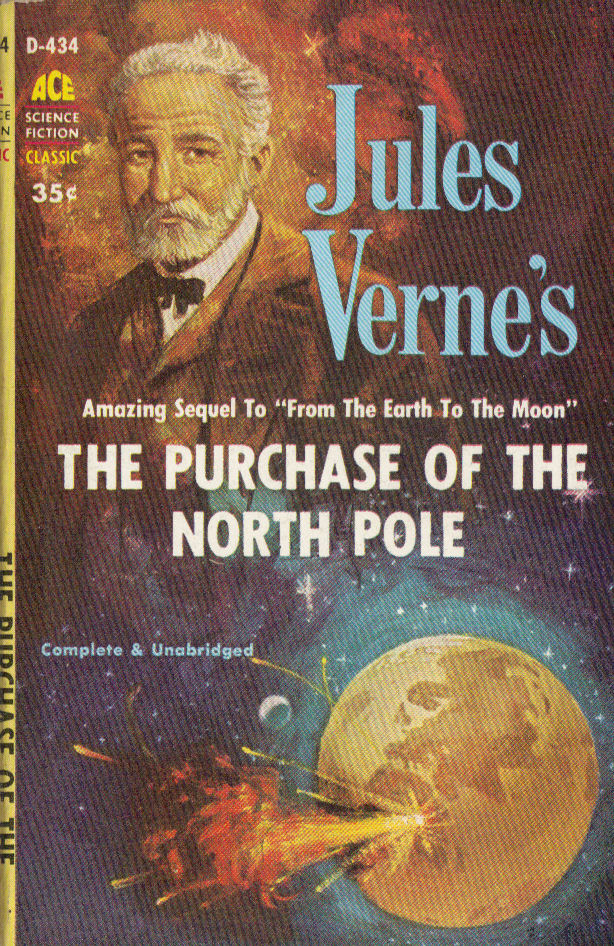

| Comparative cover art for The Purchase of the North Pole reveals the poor quality of covers in the Fitzroy edition: the Associated Booksellers edition from 1966, versus the 1960 Ace Books paperback, not part of the series | |

During this second year, 1960, the line, “Edited by I.O. Evans, F.R.G.S.,” (Fellow, Royal Geographical Society) occasionally replaced by a listing as translator, appeared. However, drastic abridgment continued to be a keynote. This was first the case with his Propeller Island to 192 pages–as opposed to over 350 in the translation he used. Evans outsourced The Mystery Of Arthur Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe and Jules Verne to Basil Ashmore. While recognizing the literary and commercial merit of combining the two volumes, the Poe original and Verne sequel, into a single volume for the first time, it was negated when the formidable length impelled a major trimming to fit the standard Fitzroy size.

Continuing the polar stories, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras began the consistent process of splitting long novels into two volumes, rather than condensing them into a single book–a process sometimes confusing to the book buyer and reader, but ultimately more reflective of the sources, and more respectful of the integrity of the texts than the years under Hanison. [32] The other volumes published that year were from shorter novels: For the Flag and Black Diamonds. 1960 was rounded out with a new and more positive development, although not without irony. The first never-before translated novel which Evans chose was thoroughly science fiction, The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission–in two volumes (Into the Niger Bend and The City of the Sahara), and for the only time in the series, wraparounds to the dust jacket announced, “First Publication in English.” However, unknown to Evans, this last posthumous volume of Jules Verne was entirely the work of his son, Michel.

The Associated Booksellers edition of The City in the Sahara in 1960 with the unique wraparound calling attention to its status as the first English translation. Other publishers’ editions of this work are shown below.

Given Evans’s long-standing interest in Journey to the Centre of the Earth, as well as his fascination with geology and spelunking, his new translation in 1961 was inevitable (although the book had been translated anew already in 1956, by Willis T. Bradley). It became only the second Fitzroy volume to exceed the standard 190 pages.

The dust jacket for Evans’s 1961 translation of Journey to the Centre of the Earth in the Fitzroy edition included two scenes from the hit 1959 screen version, despite Evans’s general disdain for Verne in the cinema.

In the wake of the Verne movie, Master of the World, which combined both Robur books and had been labeled by Evans as the “nadir of absurdity,” in 1962 the Fitzroy edition published both The Clipper of the Clouds and Master of the World. [33] More important that year was the first translation of two long, posthumous Verne novels, both again from texts which Evans did not know had been modified by Michel in major ways from his father’s work: The Golden Volcano and The Survivors of the Jonathan. [34]

Even as Evans was busy with the Jules Verne series, it was sufficiently successful that Arco asked him to undertake another Fitzroy series, an edition of Jack London. Unlike the Verne volumes, the London Fitzroys were variable in length, although once more they were edited and introduced by Evans; 21 volumes appeared before the series concluded in 1970. [35]

In 1963, Evans added one new Verne translation of his own, again of a posthumous novel, The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz, followed by his editing of another gothic tale, Carpathian Castle. Family Without a Name and North Against South, both of Verne’s longer novels of rebellions in the Americas, were timely reissues, the former because of the modern Quebec separatist movement, and the latter because of the phenomenal literary and historical interest in the Civil War, especially in the conflict’s centennial. [36] Nonetheless, despite Verne’s pro-union and anti-slavery sentiments, North Against South contained old-fashioned elements amplified by the translation, and Evans’s editing made few changes to meet the changing standards brought about by the Civil Rights movement. By contrast, that same year Evans gave a less racially charged adjustment in retitling the book previously known in English with the word “Chinaman” to instead be The Tribulations of a Chinese Gentleman.

The Associated Booksellers edition of The Tribulations of a Chinese Gentleman, 1963.

Evans had a respect for the Victorians, and he sought to cast Verne as a man who reflected his own values, often apologizing for Verne’s sometimes harsh view of his nation and its countrymen. For instance, he cut portions that served a larger purpose, such as the chapter in The Steam House (1880) where Verne explains the historical background to the 1857 Sepoy Rebellion in India. [37] While these excisions suggest conservative leanings, and he viewed his nation’s global decline with regret, politically Evans was a Socialist. One of his first adult volumes he edited was An Upton Sinclair Anthology, published in London, New York and Los Angeles in 1934, the year that Sinclair failed in his bid for Governor of California even at the high tide of the New Deal.

The patterns resulting from Evans’s helming of the Fitzroy series had become evident. Regarding Verne as more “a geographer than a story-teller,” who “adopted the fictional form largely because it was the best way of conveying the information which so fascinated him,” [38] he defended himself in an essay published in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne in 1968:

Even during Verne’s time, certain parts of his narratives must have been considered off-putting. And the contemporary public, partly as a result of radio and television, no longer has the patience to assimilate long passages of geographical information, many of which are outdated.

Instead, I tried to remain faithful to the spirit of Verne, presenting him in a manner that would please today’s readers. And the fact that these corrected versions now number 60 volumes shows that I was not mistaken. Stripped of their excessively long passages, Verne’s stories take on a new life. [39]

This was the official version, Evans arguing he was given a free hand, but based on his correspondence with him, Ron Miller reported to the Jules Verne Forum that “This policy, by the way, was forced on Evans by his original publisher.” [40] Whatever the full truth, at the very least commercial needs were a driving force.

When it came time for another triple decker in 1964, Evans repeated his error in condensing The Mysterious Island, abridging the 1876 Ward, Lock and Tyler translation of Captain Grant’s Children into two books. [41] By this point the Fitzroy series was no longer emphasizing science fiction, but acknowledging that as much of Verne’s writing belonged to the adventure genre. Evans abridged Meridiana and retitled it Measuring a Meridian, and edited Two Years’ Holiday into two volumes. [42]

Evans also offered new translations, beginning with The Village in the Treetops. Salvage from the Cynthia; or The Boy on the Buoy (a subtitle added by Evans, believing Verne would have relished the pun), had in fact already been translated in 1885 by Munro in New York as The Waif of the Cynthia. Evans should have also been deterred by the by-line shared with Paschal Grousset, considering that so many other Verne books had not been included in the Fitzroy series; the book is now known to be almost entirely Grousset’s handiwork.

Evans regarded Verne’s short stories as “inferior to his longer works.” [43] This was less of a problem with the Fitzroy Edition entitled Dr. Ox, and Other Stories, in which “A Drama in Mexico” appears instead of a reminiscence by the author’s brother, Paul Verne. However, Evans took a far more drastic approach the next year, 1965, with Yesterday and Tomorrow, making it a case study of the strengths and shortcomings of the Fitzroy series. While Evans capably translated portions, Michel's changes had yet to be discovered, and Evans further rearranged and distorted much of the book's contents. He retained, with fresh English renderings, “The Fate of Jean Morénas,” “The Eternal Adam,” “In the 29th Century: The Diary of an American Journalist in 2889,” and “Mr. Ray Sharp and Miss Me Flat” (a more accurate translation to preserve the point of Verne's title in musical notes in English would have been “Mr. D Sharp and Miss E Flat”). Evans eliminated both “The Rat Family” and “The Humbug,” two stories that dealt satirically with evolution, and as a result they would not appear in English until the 1990s. In their place, Evans arbitrarily substituted unrelated items: “An Ideal City” (a speech speculating on Amiens in the year 2000), “Ten Hours Hunting” (an autobiographical anecdote, published in the first French, but not the English, edition of The Green Ray), along with his versions of “Fritt-Flacc” and “Gil Braltar” from Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine.

Following in the vein of the new translation of some of the shorter stories in Yesterday and Tomorrow, Evans offered a new long book, The Thompson Travel Agency, without knowing that it, as in the case of The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission, was the work of Michel Verne. [44] For books that had already appeared in English, The Chancellor was followed by The Blockade Runners, itself combined into a single volume with The Green Ray.

Influences and Crosscurrents

During the years of the Fitzroy series, Evans kept up a frenetic pace with other commercial writing, making his sometimes slipshod methods on the Verne series understandable. Following a series of stories written for broadcasting by Willis Hall, and with this as a beginning, Evans completed They Found the World in 1960, a juvenile book on explorers, editing it and writing chapters on Livingston, Peary, Byrd, and the Everest and Commonwealth Expeditions. In 1961, Exploring the Earth, and The Boys' Book of Rocks and Fossils, followed. A year later came Inventors of the World, spanning Archimedes and da Vinci to modern television, radar, and jets; Engineers of the World appeared in 1963. [45] He edited The Observer's Book of the Sea and Seashore in 1962 and in 1966 two anthologies appeared, Science Fiction Through the Ages 1, on the genre before the 20th century, and Science Fiction Through the Ages 2, carrying it to the present.

In 1965, the Fitzroy series began to pay dividends when Panther paperbacks issued both Verne and Jack London volumes. The half-dozen Verne titles were Five Weeks in a Balloon, Black Diamonds, Carpathian Castle, Propeller Island, The Mystery of Arthur Gordon Pym, and The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz. Also, Consul issued City in the Sahara, but without the first volume, Into the Niger Bend.

|

|

| The first British paperback versions of the Fitzroy edition ranged from the 1965 paperback for Five Weeks in a Balloon to the Consul of City in the Sahara | |

That same year, New York University professor Walter James Miller proved that it was possible to reach the same audience of literate adults at which the Fitzroy series aimed, with a new, avowedly accurate translation. While there had been other equally complete English translations during the years of the Fitzroy series, none before Miller’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea had made the case to readers of the sad state of the old translations and the need for new renderings. Miller’s edition was published by Washington Square Press in both hardcover and paperback editions, and became a book club selection and a High School student edition.

Evans, now past 70 years of age himself, enunciated many of the same conclusions that same year in his 188 page literary study, Jules Verne and His Work. Published by Arco, the primary company behind the Fitzroy edition and doubtless intended as a companion volume, in the United States it only appeared the following year from Twayne, rather than Associated Booksellers, the company issuing the Fitzroy edition here.

Perhaps in the course of his researches, Evans had been made more aware of the problems and regretted some of the early volumes in the series. He spoke no less eloquently than Miller of the problem in his chapter adapted from an adage of George Bernard Shaw, “Translations and Tomfooleries.” Evans noted that, despite their literary quality, Verne’s books were initially aimed at youth: [46]

In Britain an authorized translation of his works, after being serialized in the Boy's Own Paper, was published by Messrs Sampson Low Marston and Co., and his more popular stories were produced independently by other firms. The translations vary greatly in quality: most are excellent but … It soon became clear that some of the translators were allowing themselves a certain freedom in adapting his work, many of their alterations being hard to understand. It is easy for British readers to see why the German student Axel, in Journey to the Centre of the Earth, should be made half English, but not why Professor Lidenbrock should be renamed Hardwigg! This freedom, too, extended to the titles … some books had four or five different titles, and for others the English title bore no relation to the original at all! [47]

Evans viewed more judiciously a tendency he had formerly endorsed, the emphasis on plot essentials, in a critique that could well be applied to the Fitzroy series. [48] As he wrote, “Not all these omissions were judicious, however, some retaining irrelevant detail while more important material was cut out, and some of the stories being arbitarily curtailed—just to fit the space available in the periodical which first published them.” [49]

He continued with a broadside against translation errors and clumsiness in diction, despite the frequency with which he had perpetuated them himself. However, when it came to actually implementing his knowledge of the issue, Evans took an approach very different than Walter James Miller. Evans used the Sampson Low version of Hector Servadac from 1877 as the source for his 1965 two volume edition, inventing new volume titles. [50] Fortunately he knew better than to use the Edward Roth rendering of this novel, but his explanation suggests he chose such versions as those of Sampson Low for nationalistic reasons, not for possible copyright or contractual arrangements:

Efficient or otherwise, however, the British translators were trying to convey to their readers not what they thought Verne should have written but what he actually wrote. But Edward Roth, the perpetrator—he can hardly be called a translator—of American versions … had the effrontery to explain that he was 'writing in the style which Verne himself would have used if addressing himself in English to an American audience'…. He vulgarized the language, not making it 'sexy' but just cheap and slangy. He needlessly altered some of the characters' names and, though this clashed with the illustrations, their appearance. In short he made Verne write as though he were not Jules Verne but Edward Roth.

Evans laments the 1960 Dover paperback reprint of Roth. “With an effrontery even greater than that of Roth himself, the American publishers announce them as 'the most faithful and readable version'. It is a pity that a reputable British firm has associated itself with these atrocities, but surely they would not have done so had they known the facts.” [51]

Such a verdict opens Evans to greater criticism of his own selections, and his treatment of them. This is particularly true considering the approach Evans took to the only extant translation of The Chase of the Golden Meteor, from the English firm of Grant Richards in 1909. While he evidently examined the French, changing the title to The Hunt for the Meteor for its 1965 appearance in the Fitzroy series, he retained the other arbitrary changes to the text. The translation had rearranged paragraphs, cutting adjectives and sometimes whole sentences, and these faults remained, even such anachronisms as the constant use of the lesser-known “bolide” or outdated “milliard.”

While trying to shift the debate about the author in the footsteps of his ongoing "Fitzroy" edition, Jules Verne and His Work was flawed, like the series itself, by its own author’s idiosyncratic perspective. Yet his eclectic approach was distinct from his predecessors, insightfully combining biographical and critical approaches to historiographically demonstrate the depth of Verne's cultural impact. Jules Verne and His Work was as well received as Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction had been. [52]

The End of the Fitzroy Series and the Last Years of I.O. Evans

Although it might seem that the similarity of the remarks on translation by Evans and Walter James Miller would have administered a coup de grace to the intellectual and commercial rationale of the portion of the Fitzroy series that relied on the existing translations, the books that appeared in 1966 reflected no change. The Flight to France was followed by The Purchase of the North Pole, while Caesar Cascabel and The Fur Country were each published in two volumes. [53]

Evans could hardly be taken to task for not knowing that The Southern Star Mystery was, in fact, almost entirely by Paschal Grousset. However, Evans was at his worst in handling The School for Crusoes, second-guessing the author by proclaiming it “too long for its central idea,” asserting he thought it would been better “as a ‘long-short’ story” or novelette. As a result, his introduction admitted that the narrative “has been drastically pruned in the present edition,” one of the few occasions he would reveal the extent of his changes. [54]

The Associated Booksellers edition of The School for Crusoes, 1966

While the paper quality and binding of the Fitzroy Edition was often declining still further, the dust jacket art had generally improved, now the creation of William Langstaffe. In 1967, the last year of the Fitzroy edition, The Giant Raft became the last of Evans’s abridgements, finishing year with a series of new translations. [55] Only one of these, Around the World in Eighty Days, had appeared in English before.

A Drama in Livonia, The Danube Pilot, and The Sea Serpent were translated from copies picked up during visits to France in 1963 and 1966, the latter for a Verne exhibition. [56] The Sea Serpent had a curious background, as he explained:

Other scarce Verne's [sic] had to be hunted for in the bookshops during my visits to France, and in one I found half-a-dozen 'remaindered'—and as yet untranslated. Sending the others on by post, I kept one for which I had a special use.

When at the Customs I was asked if I had anything to declare, I looked as furtive as I could, leaned forward and muttered confidentially that I had bought one book—'the sort of thing one can't get in England'.

The Customs Officer glared at me suspiciously and demanded to see it. But he relaxed and smiled as he waved me on when he saw the jacket. It displayed a three-master, a giant octopus, and a scared-looking seaman. And its title and author? Le Serpent de Mer by Jules Verne! [57]

This title was actually devised by the publisher Hachette, successors to Hetzel, who changed the original French title from Les Histoires de Jean-Marie Cabidoulin upon publishing the novel in 1937 in the Bibliothèque Verte. [58]

In 1970 the Fitzroy edition was about to achieve its greatest visibility in America with a series of mass market paperbacks from Ace Books, publishers of recent editions of an abridged and modernized Off on a Comet and The Purchase of the North Pole in 1957 and 1960 respectively, the latter from the Ogilvie translation, not the one Evans had used. The Ace lineup had also included Bradley’s new translation of Journey to the Center of the Earth in numerous editions from 1956, and the movie tie-in edition of Master of the World in 1961 (containing both Robur novels). To a large degree these were brought about by Verne aficionado Donald Wollheim, who had joined Aaron A. Wyn in 1952, adding science fiction to the lineup of the new paperback book list. Wollheim had also secured Bradley’s translations of “The Eternal Adam” and “Frritt-Flacc” for Saturn. With Ace’s successful reissue of long out-of-print Edgar Rice Burroughs novels in the early 1960s, Verne seemed promising. Ace contracted to produce the entire Fitzroy series, beginning with the two volumes of The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission, followed by The Begum’s Fortune, Yesterday and Tomorrow, Carpathian Castle, The Village in the Treetops, The Hunt for the Meteor, For the Flag, and the two volumes of The Steam House. These selections were all different from those of Panther. As Wollheim explained, “I tried to select the odd items from those available—and think I did get some very obscure ones. The cover artist, Podwill, was a pro illustrator who also happened to be a Verne fan himself and we got some nice cover illustrations from him. The sketch of JV we used [on the title page] was one of the very first sold pictures of Ron Miller (while he was still an art student).” Like the Panther volumes, Ace offered colorful, dynamic art, far more evocative than the hardcover editions. I vividly recall first discovering these; from a reader’s perspective, to own a reasonable facsimile of lesser-known Verne titles for 60 cents was a remarkable opportunity, when for a youth even the very reasonably priced hardcover Fitzroys at $3 represented an investment. However, sales were not adequate to continue the series, and in 1971 Wollheim left Ace. [59]

|

|

| The 1970 paperback publication of the Fitzroy series in the United States by Ace Books included The City in the Sahara and Yesterday and Tomorrow, with far superior cover art to the original dust jackets of the hardcover versions | |

Evans’s competitors were increasing in number, and the success of Walter James Miller's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea led to Signet commissioning another new translation from his New York University colleagues, Mendor T. Brunetti, in 1969. Robert and Jacqueline Baldick offered new translations of Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1965, Around the World in Eighty Days in 1968, and From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon in 1970, as did Harold Salemson of the latter the same year; throughout the decade of the space race these novels had renewed attention. Other renderings were at the worst end of the spectrum. A 1967 translation by Olga Marx for Holt Rinehart and Winston of A Long Vacation condensed it vastly more than Evans; Lowell Bair also took an axe to The Mysterious Island in 1970 to produce an 184-page Bantam paperback. Scholastic books used its unique access to American classroom sales to sell abridged editions of the worst 19th century renderings of Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, The Mysterious Island, and From the Earth to the Moon (not including, nor advising readers of the existence of, Around the Moon), along with the worst biography of the author to appear in English, Franz Born's Jules Verne: The Man Who Invented the Future (1964)—a book whose many errors were compounded by a wretched translation from the German. Against such competition, the virtues of Evans’s efforts are evident.

|

|

| The Netherlands publication by Ridderhof in 1974 of translations of some of the Fitzroy edition included De stad in de bomen (Le Village aérien, titled The Village in the Treetops in the English edition), and the two volumes of The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission; shown here is the second volume with the title variant, Een stad in de Sahara (The City in the Sahara) | |

A far more curious follow-up occurred when in 1974 a Netherlands publisher, Ridderhof, issued four Verne titles from the Fitzroy edition, De stad in de bomen (Le Village aérien), Het fortuin van de Begum, and the two volumes of The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission with their original title variants, Een missie naar de Niger and Een stad in de Sahara. New cover art was even offered, again as vibrant as the Ace books versions. In 1978, Ridderhof republished Het fortuin van de Begum and Een missie naar de Niger in a slightly larger size, this time with a Dutch translation of the introductions by I.O. Evans. While at first the idea of translating Verne from the Fitzroy edition rather than going to the French seems absurd, from a strictly commercial standpoint it gained not only the introductions, but more importantly the text already streamlined for modern readers. A few scattered reprints of the Fitzroy edition have also continued to appear in the United States and England. [60]

This cover design for the reprint of Propeller Island was typical of the dust jackets originated by Granada in the late 1970s

In his bibliography at the end of Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, Evans had established the list of untranslated books, and he failed to take into account only one other book not previously in English, Le Comte de Chanteleine, which he described as immature. [61] Evans had listed three stories in error, L’Épave du Cynthia, “Frritt-Flacc,” and “Gil Braltar.” By the conclusion of the Fitzroy series, he would have rendered nine of these novels into English, while leaving four (Le Superbe Orénoque, Les Frères Kip, Bourses de voyages, L’Invasion de la mer) for a subsequent generation–hardly a minor accomplishment. The fact that Evans neglected some works actually by Verne, while translating all the works revised or originated by Michel, today allows English-language readers to better evaluate the son’s accomplishments, especially now that most of the texts he worked from have also been published in English.

While the Fitzroy edition includes all of Verne’s books published by Hetzel through 1882, thirteen books that had already appeared in English after that were not included. Some of these would have had special interest for the Fitzroy readers, notably Mistress Branican (1891), Foundling Mick (P’tit-Bonhomme, 1893), and The Will of an Eccentric (1899), which take place in Australia, Ireland, and the United States, respectively. As for the others, Evans described Keraban the Pig-Headed (1883) as a “short-lived” play and “a mediocre book.” [62] He placed Claudius Bombarnac (1893), Captain Antifer (1894), Clovis Dardentor (1896), The Will of an Eccentric, and The Lighthouse at the End of the World (1905) as among Verne’s “second-raters,” a category into which he also placed Le Superbe Orénoque, Bourses de voyages, and L’Invasion de la mer, accounting for his neglect of them. [63] However, The Archipelago on Fire (1884), A Lottery Ticket / Ticket No. 9672 (1886), Mistress Branican, and Foundling Mick do not receive such a negative evaluation, nor did the untranslated Les Frères Kip. Despite a translation still under copyright, Their Island Home and The Castaways of the Flag (which together formed Seconde Patrie, 1900), and which was disparaged in Jules Verne and His Work, was intended to be included in the series according to the introduction to A School for Crusoes in 1966. The exclusion of Mathias Sandorf (1885) is perhaps least comprehensible, given that it was the only science fiction title left out, although length may have been an issue—not that this had stopped Evans from condensing the other triple deckers, Captain Grant’s Children and The Mysterious Island, into two-volume Fitzroys.

The Fitzroy series did not end as a result of Evans’ decision, or a firm one by a publisher. At the beginning of 1969, Evans wrote Ron Miller that “it is not yet certain whether the edition is to continue. ‘Off the record’ however, I should add that Mr. Kjellberg is not exactly objective about such projects. Some of the ideas he puts forward to me for work on Jules Verne are utterly impracticable!” [64] Most of the books remained in print for over a dozen years, and in the United States after the closing of Associated Booksellers the remaining stock was handed down to a succession of other distributors before ultimately becoming highly collectible on the antiquarian market. The books that cost $3 new in the 1960s can easily go for $100 on today’s market, losing their original purpose of disseminating his stories to the widest possible audience.

In the years following the two Fitzroy series, Evans remained active, contributing to periodicals, and authoring Benefactors of the World in 1968, a profile for young readers of thirteen individuals who aroused the world to the plight of the unfortunate, such as Braille, Nobel, Durant, Shaftesbury, Keller, and Churchill. In 1970, he completed his late friend Bernard Newman’s account of the secret service, Spy and Counter-Spy. By this time letters reveal that Evans was becoming concerned with his health and that of his wife, who was virtually blind. [65] Returning to early loves, he composed Flags of the World and Flags Illustrated in 1970, followed by The Earth, revised in 1973. His Observer's Book of Geology followed in 1971, with Rocks, Minerals and Gemstones (1972) a year later; with Kenneth Alvin, Evans wrote The Observer's Book of Lichens, published in 1977. [66]

By 1963, Evans mentioned in private correspondence that “Thanks to helpful friends and some lucky ‘finds’ I have had the pleasure of translating some little-known Verne masterpieces which have not hithereto found their way into English.” [67] While he never acknowledged such assistance in print, he may have known members of such British groups as the Jules Verne Confederacy, and he was almost certainly in contact with members of the American Jules Verne Society. This is especially true since he used the title, The Village in the Treetops (hardly a literal rendering of Le Village aérien) first mentioned in a 1944 letter from Willis Hurd describing his own unpublished translation efforts. Evans may not have felt it necessary to ascribe a precedent if he reworked the translation, no less than he did not cite the source of the other existing translations he utilized, and his one acknowledged instance, The Mystery of Arthur Gordon Pym, provides a precedent. This might provide an explanation of his extraordinary annual output, not only of Verne, but the Jack London series, and many other books. Evans did not mention the other Verne translators in his time, most notably repeatedly ignoring the three new translations by Willis T. Bradley. Evans wrote in 1956, “To my great regret I have been unable to quote from Verne's latest books, for these appear unobtainable, either in translation or in the original, and for this reason I could not, as I hoped, include the very last of his works, “The Eternal Adam,” but Bradley translated it the next year, in the March 1957 issue of Saturn. [68] Not only did the Evans translation of “The Eternal Adam” follow that of Bradley, but so did the Evans versions of Journey to the Center of the Earth and “Frritt-Flacc.”

The deplorable cover of the Associated Booksellers edition of The Village in the Treetops, 1964

In the late 1960s, he joined the Société Jules Verne in France, as well as the Dakkar Grotto, a group of Verne enthusiasts formed in the wake of the American Jules Verne Society. It resulted in two issues of a journal entitled Dakkar, after Captain Nemo's original Indian name, and Evans wrote an article on Well’s War in the Air for the second, July 1968 issue of Dakkar. This issue also contained his article on Verne’s Iceland, which appeared in translation in the tenth issue of the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne in 1969, with the original text reprinted in the March 2010 issue of the North American Jules Verne Society quarterly, Extraordinary Voyages. (Evans wrote a book, Let's Visit Iceland, published in 1976.) An article for the planned but unrealized third issue of Dakkar, on Verne and Evolution, was finally published for the first time in the same issue of Extraordinary Voyages.

Evans authored a vigorous defence of the Fitzroy series and the strategy he brought to it, ironically not for English publication, but as “Jules Verne et le lecteur anglais,” for issue six of the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne in 1968 (publication had begun only a year earlier). Other contributions to the Bulletin were an article in 1969 on the cryptogram in La Jangada, and another in 1975 suggesting an 1840 British book, Great Sea Dragons, by Thomas Hawkins, as the source for the sea battle between the dinosaurs in Journey to the Center of the Earth.

In 1976, Jules Verne and His Work was reprinted by Aeonian Press. Evans assisted Peter Haining with his books on Poe and Verne, translating Verne’s 1864 essay on Poe, “Edgard [sic] Poe et ses Oeuvres,” the Frenchman’s only major piece of literary criticism. It appeared in 1978 in complete form as “The Leader of the Cult of the Unusual” in The Edgar Allan Poe Scrapbook, and in much abridged form under the title of “The Bizarre Genius of Edgar Poe” in The Jules Verne Companion. The latter volume also included “The Future for Women,” Evans’s translation of an address Verne delivered on July 29, 1893 to the Awards ceremony at the Girl's School in Amiens, which Evans thought would be of interest given the modern feminist movement.

Haining’s acknowledgements in The Jules Verne Companion form an appropriate epitaph for Evans,

whose knowledge and love for the works of Jules Verne has done much to popularize him among English-speaking readers. He was always generous with advice and not only secured several of the very rare Verne items which appear in this book for the first time, but also made the translations with enthusiasm and care. It is to my great sorrow that he died before he could see the fruits of his efforts in finished form. [69]

Evans passed away at age 82 on February 13, 1977, and he was eulogized in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne. His contributions to science fiction scholarship were celebrated in the 1980s when Borgo Press inaugurated their series, “I.O. Evans Studies in the Philosophy & Criticism of Literature,” which continues to this day.

The Fitzroy Edition in Retrospect

Since the abridgments in the Fitzroy series of Jules Verne were telegraphed in his introductions and commentaries, this aspect of Evans’s efforts probably deserves the least criticism. A far more besetting sin was that there seems to have been no effort at selecting the best translations; even considering the strenuous schedule, such an examination would have eased Evans’s task. He was perhaps unaware of Willis Hurd’s article, “A Collector and His Jules Verne,” in the August 1936 issue of Hobbies, recounting the many different translations, often drastically edited, and the manner in which publishers often issued the same novel under widely divergent titles. However it is impossible that Evans did not know of the work of his countrymen, K.B. Meiklem and A. Chancellor, members of the Jules Verne Confederacy. Although not as rigorous as Hurd, they included a bibliography noting translators in their introduction to the Everyman's Library edition of Five Weeks in a Balloon and Around the World in Eighty Days in 1926, arguably the best critical overview on the author in English up to that time. It was updated in the 1940s, and reprinted as late as 1966. The surprisingly insular Evans would have profited from these essays, whose lessons were widely known; the New York Herald Tribune review of Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction commented that Evans “insists upon using the wretched original translations….” [70]

At the start of Fitzroy edition, Evans recalled, “We naturally expected the task to be fairly simple, needing only omissions and corrections of printer's errors and so forth. I soon learned our mistake: many of the existing versions—by no means all—were in such stilted language that they had to be largely rewritten. There were occasional gross errors in translation, and sometimes the translator had got so bogged down in the technical detail that it was impossible to see what he meant.” [71] Commencing with modified versions, Evans sometimes repeated them largely intact, but other times changed them so substantially that they are almost his own originals. From the evidence of retaining the translator’s changes in character names in such novels as The Mysterious Island and The Begum’s Fortune, he does not seem to have necessarily examined the English texts against the French. His view, as noted in Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, was that, “I have adhered to the original translations, for the form in which Verne reached the English speaking world is part of his literary history.” [72] Hence, the Fitzroy edition sought to reconcile the fundamentally inconsistent goals of perpetuating the liberties of past translations, while also attempting to make them more acceptable to a new generation.

Beyond simply republishing older editions, once the Fitzroy series began to appear from Arco, Evans offered translations of books not previously in English. His original translations were in a more modern, readable, reasonably faithful style. This was the second and most important achievement of the Fitzroy series, and the one for which Evans deserves the most praise, for many of these novels have not been published again. So, too, in offering prefaces, Evans provided regular critical background and analysis.

While lamenting the imperfections of the Fitzroy series, it must be remembered that in Evans’s time, many of these titles were becoming otherwise inaccessible, and the story of Evans and the Fitzroy series is also the story of Anglophone Verne publishing from the mid 1950s through the mid 1970s. Seventeen Verne books appeared from other Anglo-American publishers during the 1950s through the 1970s, but the Fitzroy edition encompassed these along with nineteen more books that only reappeared thanks to the series, and nine more titles in the first English translation. [73] (In the forty years since the Fitzroy series, only fourteen of the titles have been superseded in terms of translation quality and critical commentary. [74] ) Ultimately comprising an impressive forty-eight separate stories in sixty-three volumes, the series had a commercial penetration unimaginable today. I well remember that even before the widespread dissemination of the Ace paperback editions, scattered hardcover volumes could be found in the larger bookstores, and smaller public libraries routinely had at least some volumes in the series, while larger downtown libraries, to judge by my native California, had nearly all of them. Evans may have somewhat distorted Verne, no less than the cycle of Hollywood and comic book adaptations that coincided with the series, but like them, he gained new enthusiasts for the author by making most of Verne’s stories available to the first new generation since the 1920s.

The jury is in and the verdict can only be mixed. Evans remains a frustrating figure, since despite his Herculean labors, he did not take the few additional steps toward more rigorous scholarship that would have made him at least the grandfather of the Verne Anglophone renaissance that began even as the series was underway. He was both Verne’s best friend and his worst enemy; his pioneering work merits praise while he amplified the problems that plagued previous Verne translations. As a professional writer and scholar, he was creative and practical, mindful of commercial necessities, perhaps too willing to make compromises toward a larger goal. Nonetheless, his efforts did make the vast majority of Verne's works again available&mdas;along with many for the first time&mdas;and one can only wish that the Fitzroy series had continued, as was intended, to encompass Verne's entire oeuvre. Taking advantage of a publisher’s unique willingness to invest in Verne, Evans’s creation of such a major Verne series is unequaled, and it is difficult to imagine it will be surpassed.

NOTES

- Details are drawn from the only existing comprehensive biographical account of Evans, in Contemporary Authors Online (Gale, 2002), entry updated October 29, 2002, accessed through Biography Resource Center, March 1, 2010.. ^

- “Preface,” in I.O. Evans, From Wonder Story to Science Fiction, unpublished manuscript, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library; I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1956), viii; I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work (New York: Twayne, 1966), 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 11; I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, vii. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, vii. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, March 25, 1957, p. 2, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- I.O. Evans, The Junior Outline of History (London: Denis Archer, 1932), 259. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, May 17, 1953, p. 1, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, March 19, 1957, p. 1, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- I.O. Evans, The Junior Outline of History (London: Denis Archer, 1932), 259. ^

- Peter Nicholls, Science Fiction Encyclopedia (London: Granada, 1979). The World of Tomorrow, like his The Junior Outline of History, appeared in Chinese translation. ^

- http://homepage.ntlworld.com/farrago2/rafsite/het/footnotes/fanac1.htm, accessed April 15, 2010. Another article, “Can We Conquer Space?,” followed in the Summer 1938 issue of Tales of Wonder. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, March 19, 1957, p. 1, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library; I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, vii. Among these were Gadget City–A Story of Ancient Alexandria (1944), Strange Devices–A Story Of The Siege Of Syracuse (1950), The Coming of a King–A Story of the Stone Age (1950), and Olympic Runner–A Story of the Great Days of Ancient Greece (1955). ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, March 31, 1957, p. 1, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, March 31, 1957, p. 2, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, xviii-xix. ^

- I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, xviii-xix, viii. ^

- I have only noted the French title when the English used by Evans departs significant from the original and the source might otherwise be unclear. ^

- Evans’s version of “Gil Braltar” was reprinted in The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, 8th Series, in 1959. “Gil Braltar” first appeared in France with the 1887 volume, Le Chemin de France, but was left out when the book was translated and published the following year by Sampson Low as The Flight to France. Two copies of a unique little hand-bound edition entitled “Gibraltar” were made by Willis E. Hurd and William E. Walling of an English translation by Ernest H. De Gay in 1938, one of the efforts of the American Jules Verne Society of the time, which survives in the Library of Congress. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12. ^

- I.O. Evans, “Jules Verne et le lecteur anglais,” Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, No. 6 (1968): 4. ^

- Fitzroy Street was a famous street in central London in the heart of Bloomsbury, that in the 1920s and 1930s had been the meeting place of the "Fitzroy Group" group of English artists. ^

- For comparison, the Horne series was made up of: Volume 1: “A Drama in the Air,” The Watch's Soul, A Winter in the Ice, The Pearl of Lima, The Mutineers, Five Weeks in a Balloon; Volume 2: A Trip to the Center of the Earth, Adventures of Captain Hatteras: The English at the North Pole; Volume 3: Adventures of Captain Hatteras: The Desert of Ice, A Trip From the Earth to the Moon, A Tour of the Moon; Volume 4: In Search of the Castaways: South America, Australia, New Zealand; Volume 5: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, The Mysterious Island: Dropped From the Clouds; Volume 6: The Mysterious Island: Dropped From the Clouds, The Abandoned, The Secret of the Island; Volume 7: A Floating City, The Blockade Runners, Round the World in Eighty Days, Dr. Ox's Experiment; Volume 8: The Survivors of the Chancellor, Michael Strogoff; Volume 9: Off on a Comet [Hector Servadac], The Underground City [Les Indes noires]; Volume 10: Dick Sands: A Captain at Fifteen, The Dark Continent; Measuring a Meridian [Aventures de trois Russes et de trois Anglais dans l’Afrique australe]; Volume 11: The Five Hundred Millions of the Begum, The Tribulations of a Chinaman in China, The Giant Raft: Eight Hundred Leagues on the Amazon; Volume 12: The Giant Raft: The Cryptogram, The Steam House: The Demon of Cawnpore, Tigers and Traitors; Volume 13: The Robinson Crusoe School, The Star of the South, Purchase of the North Pole; Volume 14: Robur the Conqueror, The Master of the World, The Sphinx of Ice; Volume 15: The Exploration of the World. ^

- Arthur B. Evans, email message to the Jules Verne Forum listserv, May 22, 2001; for the evaluations, unless otherwise noted, see Arthur B. Evans, “Jules Verne’s English Translations.” Science Fiction Studies, 32 (March 2005): 80-104 and Arthur B. Evans, “A Bibliography of Jules Verne's English Translations.” Science Fiction Studies, 32 (March 2005): 105-141. ^

- Ron Miller, email message to Jules Verne Forum listserv, February 6, 1997. ^

- Roger Leyonmark, email to the author, July 21, 2010. ^

- The Adventures of Captain Hatteras was issued in two volumes form as At the North Pole and The Wilderness of Ice. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 147. ^

- The Golden Volcano was issued in two volumes, The Claim on Forty Mile Creek and Flood and Flame, and The Survivors of the Jonathan as The Masterless Man and The Unwilling Dictator. ^

- Beginning with Son of the Wolf: Tales of the Far North in 1962, five more volumes followed the next year, The Cruise of the 'Dazzler'; Daughter of the Snows; Children of the Frost; The People of the Abyss; and The Call of the Wild. In 1966 the Fitzroy Edition of Jack London had resumed with The Iron Heel; Sea-Wolf; and White Fang. The Game [and] The Abysmal Brute (in one volume); The God of His Fathers and Other Short Stories; John Barleycorn, or, Alcoholic Memoirs; Martin Eden; The Road; The Game; The Jacket; and Star Rover followed in 1967. Burning Daylight; The Mutiny of the `Elsinore'; and The Scarlet Plague [and] Before Adam (two novels in one volume) appeared in 1968 before The Son of the Wolf concluded the London series in 1970. ^

- Family Without a Name was published in two volumes as Leader of the Resistance and Into the Abyss, and North Against South as Burbank the Northerner and Texar the Southerner. ^

- Arthur B. Evans, “Jules Verne’s English Translations,” 90. ^

- I.O. Evans, “Introduction,” in Evans, ed., Science Fiction Through the Ages I (London: Panther, 1966), 149. ^

- I. O. Evans, “Jules Verne et le lecteur anglais,” Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, No. 6 (1968): 5, translated in Arthur B. Evans, “Jules Verne’s English Translations,” Science Fiction Studies, 32 (March 2005): 101-102. ^

- Ron Miller, email message to Jules Verne Forum listserv, February 6, 1997. ^

- The first half of part two, On the Track was included with the first volume, The Mysterious Document, while it concluded in the second volume, Among the Cannibals. ^

- Two Years’ Holiday was published in two volumes, as Adrift in the Pacific and Second Year Ashore. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 11. ^

- The Thompson Travel Agency was published in two volumes, Package Holiday and End of the Journey. ^

- The book also included chapters on Galileo, the Montgolfier Brohers, Robert Fulton, Samuel F.B. Morse, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, Marconi, John Logie Baird, Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, and Frank Whittle. The latter, he wrote, represented the “back-room boys” without whom victory could not have been achieved in World War II. I.O. Evans, “Introduction,” in Inventors of the World (New York: Frederick Warne, 1962), 8. ^

- I.O. Evans, “Jules Verne et le lecteur anglais,” 3. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 143. ^

- I.O. Evans, “Jules Verne et le lecteur anglais,” 3. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 143. ^

- Evans entitled the two-volume Fitzroy edition of Hector Servadac as Anomalous Phenomena and Homeward Bound, replacing the more catchy English language part titles, To the Sun? and Off on a Comet!. Evans had first entitled excerpts from the book in the contents of Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction as “Aberrant and anomalous phenomena,” and remarked “I felt rather proud of myself for coining hat phrase!” I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, March 19, 1957, p. 1, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 144-145. ^

- Vincent Starrett, “Looking Back at a Prognosticator,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1967, p. L8. Despite its shortcomings, Evans’s volume remains vastly superior to the other Twayne volume, the slim 1992 Jules Verne, by Lawrence Lynch, a throwback with only a few new details to recommend it. ^

- Caesar Cascabel was republished in two volumes as The Travelling Circus and The Show on Ice, and The Fur Country as The Sun in Eclipse and Through the Behring Strait. ^

- I.O. Evans, “Introduction,” in Jules Verne, The School for Crusoes (Westport, CT: Associated Booksellers, 1966), 7. ^

- The Giant Raft appeared in two volumes, Down the Amazon and The Cryptogram. ^

- Andy Sawyer, email to the author, April 10, 2010. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 13. ^

- Fortunately, unlike many of the other Verne books in the series, this one was not modified from the original, so Evans had an accurate text to translate. I am indebted to Philippe Burgaud for making the text evaluation. ^

- Donald A. Wollheim, letter to Roger Torstenson, February 9, 1987, author’s collection. ^

- The first was Around the World in Eighty Days in 1967 and Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1972 from MacGibbon & Kee, and The Masterless Man and The Unwilling Dictator from Beckman Publications. In 1977, through 1980, Granada began issuing Carpathian Castle, The Clipper of the Clouds, From the Earth to the Moon, The Masterless Man, and Package Holiday (the latter two both only the first halves of two volume works) with Hart-Davis MacGibbon carrying on some of these titles briefly. At the same time, Amereon issued A Floating City, Anomalous Phenomena, Black Diamonds, The Clipper of the Clouds, Into the Niger Bend and The City in the Sahara (in 1976, using the Ace books plates), Master of the World in 1979, The Claim on Forty Mile Creek in 1980, The Chancellor in 1983, Measuring a Meridian in 2000, The Southern Star Mystery in 2002, and The Begum’s Fortune in 2003. Some of these were in limited editions. ^

- Le Superbe Orénoque (1898), Le Village aérien (1901), Les Histoires de Jean-Marie Cabidoulin (1901), Les Frères Kip (1902), Bourses de voyages (1903), Un Drame en Livonie (1904), L’Invasion de la mer (1905), Le Volcan d’or (1906), L’Agence Thompson and Co. (1907), Le Pilote du Danube (1908), Les Naufragés du Jonathan (1910), Le Secret de Wilhelm Storitz (1910), L’Étonnante Aventure de la mission Barsac (1919), plus the stories of the 1910 anthology, Hier et demain; Evans, I.O., ed. “Preface.” In Jules Verne, The Flight to France (London: Arco, 1966), 3.; ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 89. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 118-120. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Ron Miller, January 3, 1969, p. 1, courtesy of Ron Miller. ^

- Andy Sawyer, email to the author, April 12, 2010. ^

- The Earth, revised in 1973, was translated into Dutch, French and Spanish. Rocks, Minerals and Gemstones (1972) was translated into German and Dutch. ^

- I.O. Evans, letter to Eric Frank Russell, May 6, 1963, Special Collections and Libraries, University of Liverpool Library. ^

- Brian Taves and Stephen Michaluk, Jr., The Jules Verne Encyclopedia (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1996), 27; I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, viii. ^

- Peter Haining, The Jules Verne Companion (New York: Baronet, 1978), 128. ^

- H.H. Holmes, “Science and Fantasy,” New York Herald Tribune Books, 34 (August 18, 1967), 9. ^

- I.O. Evans, Jules Verne and His Work, 12-13. ^

- I.O. Evans, ed., Jules Verne: Master of Science Fiction, viii. ^

- During the time of the Fitzroy Edition, these titles appeared from other publishers: Five Weeks in a Balloon, Journey to the Center of the Earth, the lunar novels, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, Dr. Ox’s Experiment, The Mysterious Island, Hector Servadac, Michael Strogoff, Eight Hundred Leagues on the Amazon, The Clipper of the Clouds, A Long Vacation, The Purchase of the North Pole, Master of the World, and “The Eternal Adam.” However, these titles were perpetuated thanks to the Fitzroy edition: Captain Grant’s Children, A Floating City, The Blockade Runners, Measuring a Meridian, The Fur Country, The Chancellor, Black Diamonds, The Begum’s Fortune, The Tribulations of a Chinese Gentleman, The Steam House, The Green Ray, The School for Crusoes, The Flight to France, Salvage from the Cynthia, North Against South, Family Without a Name, Carpathian Castle, For the Flag, The Mystery of Arthur Gordon Pym, and The Hunt for the Meteor. Nine appeared for the first time in English: The Village in the Treetops, The Sea Serpent, A Drama in Livonia, The Golden Volcano, The Thompson Travel Agency, The Danube Pilot, The Survivors of the Jonathan, The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz, and The Astonishing Adventure of the Barsac Mission. ^

- These are Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, From the Earth to the Moon, Around the Moon, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days, The Fur Country, A Fantasy of Doctor Ox, The Mysterious Island, The Underground City (Les Indes noires), Hector Servadac, The Begum’s Millions, The Green Ray, and Star of the South. ^

Acknowledgments

Without the published bibliographic efforts of Stephen Michaluk, Jr., and the website of Andrew Nash, portions of this article would not have been possible. Thanks are due to Steve for additional information, along with Andy Sawyer, Frits Roest, Roger Leyonmark, Philippe Burgaud, Tony Williams, James Keeline, Ron Miller, Jon Gentilman, Pachara Yongvongpaibul, Jevon Lemonica—and to Walter James Miller for providing the title for this article in many conversations with Verne enthusiasts over the years. In addition to the sources cited, invaluable bibliographic information on books by Evans was provided by Contemporary Authors Online and Worldcat.