The Kip Brothers (Les Frères Kip, 1902) is conventionally examined as Verne’s salute to his brother Paul and an indirect meditation on the Dreyfus affair through a retelling of the incident of the Rorique brothers. Occasionally the novel’s denouement is studied as an attempt to enliven the tale with science. However, these avenues leave out a dimension, the reason Verne set such a story of injustice within the specific generic boundaries of a maritime adventure. This form’s conventions render The Kip Brothers an ideal vehicle for such a social parable, and make it the logical successor to the sea adventure’s model, the mutiny of the Bounty, an incident which Verne years earlier had made part of the Extraordinary Voyages.

I.

Because of Verne’s association with science fiction, the most noted element The Kip Brothers is the penultimate discovery, through photography, of the reflection of the last image the murder victim saw in life–his murderers. While some have seen in this a touch of science fiction, it was a common belief at the time.[1] Moreover, it occurs only in the very last pages of the novel, and is decidedly reminiscent of the restoration of the hero’s sight in Michael Strogoff, itself strictly an adventure novel without scientific aspects.

Throughout The Kip Brothers there are allusions to seeing, sight, and eyes, foreshadowing the climax of the novel. (At the time of composing The Kip Brothers, Verne was losing his own eyesight due to cataracts.) No less than for Strogoff, this deus ex machina is necessary, this time to finally bring about the revelation of the guilty party.

II.

The Kip Brothers uses the theme of two brothers, this time the idealized opposite of the evil brothers of The Steam House and North Against South. Pairs of beneficent brothers had appeared in Sab and Sib of The Green Ray, and later in Marc and Henri Vidal in The Secret of Wilhelm Storitz.[2] The title, The Kip Brothers, is expressive of its content in heightening the emphasis on the fraternal bond, and is the only one of Verne’s novels named for two siblings of the same gender.[3]

The Kips are not the only fraternal characters. The near-brotherly behavior of Flig Balt and Vin Mod, who think and act as one, provide a balance in a pair who are evil counterparts of the pure, turn-the-other-cheek goodness of the Kips. While undergoing terrible travails, from shipwreck to unjust imprisonment, the Kips resist despair and even escape when it is open to them, after helping the Fenians to assert their own independence.

Their behavior contrasts strongly with that of Balt and Mod. Repeatedly foiled by the failure of situations to favor their planned mutiny, they finally kill the captain themselves. Thus Hawkins, the ship’s owner, unaware of the truth, has little choice but to promote Balt, as second in command, to captain. He will later be dislodged from this position for incompetence, and replaced by Karl Kip.

Verne’s brother Paul, his closest friend and confidant, died the year before he began writing The Kip Brothers, and the novel is often regarded as a tribute to him, especially considering that Paul was a mariner like the Kips. Pieter Kip is primarily dedicated to the family business, while his brother has been the true man of the sea, reflecting the distinction between the Verne brothers, the man of letters and the sailor.[4] In Port Arthur, even more than freedom from imprisonment, the brothers will desire to be together. (303)

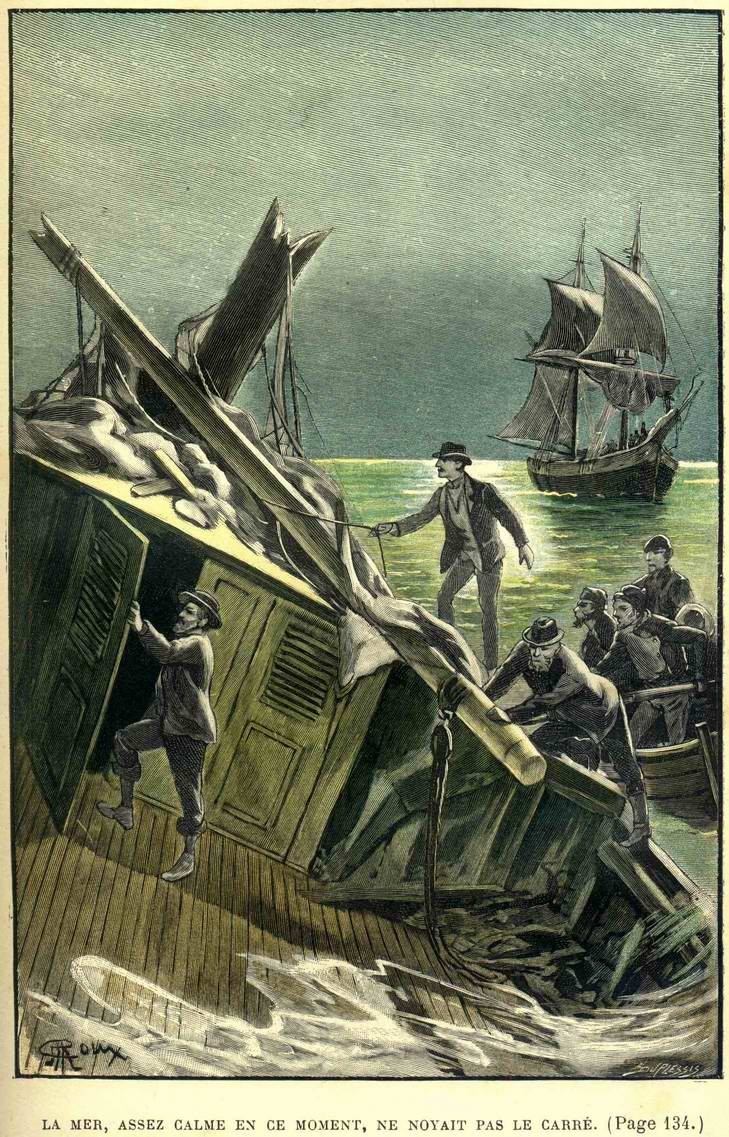

However, to focus primarily on the fraternal aspect in analyzing The Kip Brothers is a mistake, since a quarter of the book is past before the title characters are introduced, rescued from a shipwreck similar to The Children of Captain Grant and Mistress Branican. The setting and conflict are all thoroughly introduced before the Kips come on the scene.

III.

The Dreyfus affair is too well-known to need comment here, and another basis for The Kip Brothers was the Rorique brothers, accused of hijacking a schooner and several of the crew. They claimed innocence, and were sentenced to death by a French tribunal based only on the evidence of the ship’s cook. After a public outcry, upon learning of past heroic behavior by the Roriques, the sentence was successively commuted to only 20 years. Verne publicly discussed the Rorique impact upon The Kip Brothers, which he had originally entitled Les Frères Norik. At the time, even after the Dreyfus case had been exposed, the injustice perpetrated against the Roriques was considered far more serious, especially since one of the Rorique brothers had died while imprisoned, and they lacked what were regarded as the “rich and powerful” allies of Dreyfus.[5]

Such accounts of unjust imprisonment as suffered by the Roriques were not unusual at the time, and the only individual who shared a by-line with Jules Verne in his novels experienced a similar odyssey.[6] Paschal Grousset (1844 1909) wrote the first drafts of The 500 Million of the Begum (1879) and The Star of the South (1884), but received no public recognition for his contribution. Publisher Jules Hetzel had sent Grousset’s manuscripts to Verne beginning in 1877 when Grousset was a young and untried author with many literary notions similar to Verne’s.[7]

Although the arrangement might seem unfair, in fact it was necessary because Grousset was in exile. He was a leader of the Paris Commune during the siege of the Franco Prussian War, and was captured and sent along with other Communards to New Caledonia. However, in 1874, after two years in captivity, Grousset and three others escaped to Australia and a hero's welcome before continuing on to America and England. He soon became an author in his own right, known by his pseudonyms of André Laurie in fiction and Philippe Daryl in nonfiction, and was able to return to France after the amnesty of 1880. When The Wreck of the Cynthia was published in 1885, credit went to both Verne and Laurie as coauthors--although the book was largely Grousset's work, and was published outside the Extraordinary Voyages.

IV.

Hence, such accounts of unjust, and sometimes political, imprisonment, as suffered by the Roriques, Grousset, and Dreyfus were relatively common. Indeed, they were readily found both in fact as well as fiction, and one reason the Rorique’s tale had such public resonance may have been because it fit so closely the outline of a fictional adventure tale.

The Kip Brothers is another example of the words Alexander Dumas fils referred to when he spoke of the relationship between Verne and his father in the preface in Mathias Sandorf, “There is between the two of you a literary kinship so obvious that, in terms of literature, you are more his son than I am.” The Kips, like another archetypal adventurer before them, find on returning to port innocently that they are the victims of a conspiracy which sends them to the worst of prisons. Like Edmond Dantès, returning to Marseille and having inherited on the voyage a captaincy with a bright future before him, the Kips find in Balt and Mod a set of conspirators just as devious as Danglars, Villefort, and Mondego in creating a circumstantial case. Instead of the Château d’If, the Kips are incarcerated in Port Arthur. Rather than by the beneficent Abbe Faria, the Kips are rescued by the Fenians and the faith of Hawkins in proving their case.

Adventure dramatizes the exploits of the challenges faced in the past of kings and battles, rebellion, piracy, exploration, the creation of empires, and the interplay of power between the individual and national authority. What is unique to adventure is the element of altruism: the adventurer lives by a code of conduct that includes idealism, honor, patriotism, and chivalry. This impels individualistic, armed rebellions for freedom, with outlawry sometimes the only recourse against injustice or totalitarianism. Within the world of adventure, mankind's past is conceived as a progression toward responsible self government. The fundamental narrative movement from oppression to liberation encompasses such classic figures as Monte Cristo, King Arthur, Robin Hood, or his Spanish California equivalent, Zorro, and the French Revolution clone, the Scarlet Pimpernel, or, from another setting, Fletcher Christian. The adventurer must exhibit moral courage with a willingness to risk "his personal safety by attempting to perform difficult tasks" and displaying resourcefulness--“virtues such as courage, fortitude, cunning, strength, leadership, and persistence” in overcoming danger and villainy.[8] The settings, not only temporally but geographically, are remote from what is mundane to the intended audience, but do not transcend the borders of fantasy or future technology.

Adventure as a generic tradition peaked during the 19th century, celebrating the rise of individual freedom and self determination, usually in a nationalistic context. Burgeoning popular literature attracted a new readership, lower class industrial workers intrigued by the appeal to the imagination, an ingredient largely absent in the domestic novels of the educated elite.[9] The modern adventure story is generally traced from Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, but properly commences with Sir Walter Scott and Alexandre Dumas establishing its conventions.

Verne followed in their footsteps, and had learned the form by the time of his early stories A Drama in Mexico, Martin Paz, A Winter Amid the Ice, Pierre-Jean, San Carlos, and The Siege of Rome. Although science fiction was the most original and influential aspect of his work, more than half of Verne’s oeuvre belongs to different genres, primarily adventure, along with comedy and mystery.[10] The adventure formula allowed Verne to maintain his astonishing output of one or two novels annually, and his success with the genre was notable, especially with his literary and theatrical hits, Around the World in Eighty Days and Michael Strogoff.

Joining him were W.H.G. Kingston, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, Baroness Orczy, Edward Bulwer Lytton, Rudyard Kipling, H. Rider Haggard, Karl May, Jack London, and Joseph Conrad. The tradition of adventure quite naturally allied with an interest in geography and science in the “Extraordinary Journeys,” along with the now largely forgotten geographical tomes Verne authored.

Adventure heralded exploration and the establishment of overseas empires, with the inherently contradictory mix of enlightening and uplifting in the name of nationalism and Christianity, regardless of the opposition found in the distant colonial lands. Hence, the occupying race, not the rebelling natives, are portrayed as representing the move toward a freer society. Soldiering in the colonies, and suppressing native rebellion, became a formula that would proliferate throughout the popular literature of the time, especially in writing aimed at boys, the future officers of empire.[11] A new impetus to adventure writing and the development of the genre occurred with the Sepoy rebellion of 1857, central to two of Verne’s novels, The Mysterious Island and The Steam House. Popular literature sought to understand how the vaunted white imperialist presence came so close to being overthrown by a supposedly primitive Eastern people.

Vernian adventures usually concern a journey and survival, combining travel, geography, a touch of mystery, and sometimes even comedy. Unlike most adventure writers, Verne had artistic and political sympathy with colonial struggles for liberation, and his viewpoint was far in advance of the predominant white man's burden theme of the late 19th century. He preferred the sympathetic treatment of the plight of the oppressed, white or native, in such books as The Jangada, The Archipelago on Fire, North Against South, Family Without a Name, Caesar Cascabel, The Mighty Orinoco, Scholarships for Travel, and The Invasion of the Sea. In other ways, he undercut the ethics of adventure, as in his parables of greed gone amuck, Wonderful Adventures of Master Antifer (1894) and The Golden Volcano (1906).

In The Kip Brothers, conquests and its consequences are regarded as essentially inevitable, and the treatment of colonialism expresses the typical view of adventure. There are comments on the natural life of the region; Verne notes that the Maoris are on their way to disappearing, given the predominant alcoholism, especially of the women, and the missionaries causing a change in their diet away from cannibalism. (60-62) Verne mentions the death of the last representatives of the indigenous black population of Tasmania, and predicts it will also come about in Australia, under British rule. (204) However, when Hawkins speculates on outfitting the James Cook for whaling, Captain Gibson remonstrates that he will not take up that trade, echoing environmental concerns that Captain Nemo had expressed before him.

However, in a manner typical for adventure, while the impact on native peoples and culture might be viewed with equanimity, other aspects of the colonial condition, such as the injustices it perpetrated among the whites who came in contact with it, would be decried. The Kip Brothers was such a novel, with its depiction of not only the injustice under British colonial rule in distant lands.

Sentiment is against the Kips at least partly because of English nationalism. As British imperial dominion cemented its hold around the world, admirable Englishmen had begun to disappear from Verne's novels. Balt begins by claiming mutiny was justified because a Briton has the right to refuse to serve under the orders of a foreigner, “a Dutchman! ... That is what pushed us to revolt against Karl Kip.” (249) As Verne later comments, “In the general hatred felt for the murderers of Captain Harry Gibson, there entered a great measure of that egotism so visible among the Saxon races, the proof of which no longer needs to be shown. It was an Englishman who had been killed; they were foreigners, Dutch, who had been condemned.” (276)

A striking ellipsis between chapters 7 and 8, as the Kip’s sentence is commuted from hanging to hard labor, allows them to be next seen, after the Hobart Town courtroom, in Port Arthur, making the abrupt experience of prison all the more odious. “The cat-o’-nine tails, in the hand of a vigourous guard, would lash the back of the prisoner who was stripped to the waist, streaking his flesh and transforming it into a bloody pulp.” (296) While in choosing not to use such colonial outposts of his homeland as Devil’s Island, but in those of Britain, the story’s reception at home was eased, it also insured that it would not be read by English-speaking countries.[12]

With chapter 10, The Kip Brothers moves in an entirely new direction, with a fresh subplot that underlines both the anti-British elements as well as the theme of injustice, through an encounter with political prisoners. The Kips find their own sentence reflected in the simultaneous incarceration of the Fenians, O’Brien and Macarthy, who sought to free “Ireland from the intolerable domination of Great Britain...” (313) Here is another echo of Grousset’s experiences, who, after his escape and before the amnesty, lived in America and promoted the Irish cause, including writing the book Ireland's Disease. The fact that Verne includes in the mix not only the Kips who might be seen as standing in for Dreyfus/Rorique/Grousset, but also the Fenians and a general attack on British colonial practices, indicates that the novel needs to be read more broadly for embodying an overall ideology, that of the adventure genre.

Imprisoned with the Kips, the Fenians are placed alongside the worst criminal elements, with whom they have nothing in common. They had been betrayed by informers, but accepted imprisonment rather than reveal their co-conspirators. (316) Hence England is associated not only with unjust colonial rule, but maintaining power through the most disliked of personal attributes–a snitch. By contrast, says Verne, who also wrote of British oppression in Ireland in Little Fellow, “Many a time this sort of devotion could be found among the Fenians, where there exists a solidarity that goes as far as sacrificing one’s life for a cause.” (317) As Karl Kip later notes of O’Brien and Macarthy, “Their only crime is to have dreamed of independence for their country.” (331)

When the Fenians escape, they are about to be intercepted by prison guards in chapter 13 when abruptly Verne changes point of view with the intervention of the Kips. At once it becomes their story, the injustice of their own situation that is the metaphorical basis for the novel. The United States, to which the Fenians can flee and which shelters those who seek a free Ireland, is lauded, and Verne is careful to not limit their reception to the Irish-American community. “The newspapers celebrated noisily the success of their escape and gave honor to those who had prepared it, almost like a revenge of Fenianism.” (372)

V.

Verne’s previous sea adventures have a very different focus than The Kip Brothers. The Children of Captain Grant and Mistress Branican both told of a search for a shipwreck survivor. A Floating City was a travelogue, and The Blockade Runners set against the American Civil War. Wonderful Adventures of Master Antifer recounted fortune hunting carried to its extreme and ultimate failure.

The archetype of the sea adventure is the 1789 mutiny aboard the H.M.S. Bounty on the return voyage from Tahiti, with its theme of revolution and renewal in the new land of Pitcairn's Island. On July 27, 1879, Verne bought for 300 French Francs the rights to a short story telling of the Bounty from Gabriel Marcel (1843-1909), a geographer of the National Library with whom he had collaborated with Hetzel in writing the Discovery of the Earth: History of the Great Voyagers and Great Navigators Découverte de la Terre and La Conquête géographique et économique du monde. “The Mutineers of the Bounty” (“Les révoltés de la Bounty”) subsequently appeared under the Verne by-line in Magasin d’Education et de Récréation, filling out the Hetzel volume of The Five Hundred Millions of the Begum that year (itself derived from the Grousset original), with which it would be translated into English.

Sea stories, more frequently than other adventure subtypes, take up serious and complex themes. History is a frequent source (the Bounty retellings, Richard Henry Dana's Two Years Before the Mast), and a number of the best-known books are respected classics (Jack London's The Sea Wolf, Herman Melville's Moby Dick and Billy Budd), or novels of a higher literary standard than most adventure fiction (Rudyard Kipling's Captains Courageous, C.S. Forester's Hornblower series and Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Marturin series). James Fenimore Cooper, whose influence Verne acknowledged, was as much in his lifetime associated with sea stories as the Leatherstocking westerns for which he is best remembered today.

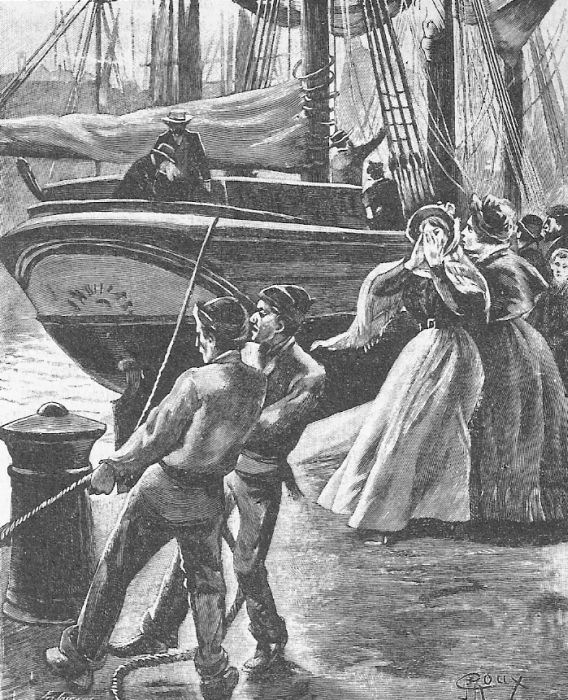

The plot of The Kip Brothers is given an element of unpredictability by its mix of every incident typical of sea adventure: a tavern from which sailors are drawn; shipwreck; rescue; repelling native boarders; dangerous storms; a villainous ship’s officer; mutiny; and the possibility of piracy. Sea adventures contrast the reality and mythology of the sea; the grace of wind, sails and rigging is counterpointed by the routine of ocean going life, revealing the rugged life of the sailor. Verne carefully etches the James Cook and crew as they prepare to launch, with the best characters naturally drawn to such a ship and the healthy, natural side of the sea, with even the cabin boy, Jim, another example of the high moral standards on board.

The first half of The Kip Brothers is a languorous travelogue serving to establish the locale and characters, with elegant descriptive passages. The sea story is initially differentiated from other adventure types by its manner of presentation, with a style considerably less romantic, more realistic, if not quite mimetic. This is echoed through the visual integration of many of the engravings from Discovery of the Earth: History of the Great Voyagers and Great Navigators, almost as many as originals for the incidents and characters of The Kip Brothers. Similarly, Verne’s version of the Bounty story is not only in this region, but visualized in the same manner with the five illustrations by Drée.

This pattern with the engravings does not repeat in the second half of The Kip Brothers, where, by contrast, the pace accelerates, from the conspiracy of Balt and Mod against the Kips onward, concentrating largely on incident. Some of the latter half reads so fast as to be almost a summary, a condensation of events as the book races toward its conclusion. This aspect was reflected in its writing, with the first half composed over four months, the second in a mere six weeks.[13]

Given the mimetic element, the sea story is the adventure type with the least opportunity for women to participate, since their presence is unlikely in such a locale in this period, not to mention the limitations which then existed on women's roles. Accordingly, in The Kip Brothers the only female character is Mrs. Gibson, who remained home in Hobart Town during her husband’s voyages, and the even lesser Mrs. Zieger.

Voyages in adventure inevitably lead to self revelation, the baring of one's true nature. As Ishmael narrates in Moby Dick, the sea is a place "where each man, as in a mirror, finds himself." It is possible to find self-improvement in the environment of the sea, as in the reformation of Harvey Cheyne in Captains Courageous.

The Kip Brothers begins in 1885, in the wake of the depredations of gold fever in British-governed New Zealand and nearby territories. Maritime discipline has collapsed under temptation, with crews eager to desert for the elusive possibility of discovering gold. Sea adventures typically include lifetime sailors or men forced into service by impressment, drifters without families. They are restless from the start, grumbling against authority and tempted toward mutiny, whether provoked or not, and are revealed in only one other conventional habitat, the tavern. Verne recognizes this in opening at such a site, from which sailors are inevitably drawn and to which they return. At the “Three Magpies,” renewing acquaintances inevitably leads to brawls. Even here, Balt’s consumption of liquor marks him as a villain where the customers are all men of ill repute. (6)

Sea adventures tend to become character studies of the captain, officers and crew, their leadership abilities, motivations, and relationships. The conventional plot concentrates on groups of men in isolated conditions, separated for lengthy periods from civilization. Living amidst the elements and outside normal social interaction, under pressure in close quarters, officers and sailors alike are faced with exhausting labors.

The sea adventure offers a notable range of admirable captains, such as the title character of the Horatio Hornblower series, himself a fictional displacement of Admiral Horatio Nelson. These are individuals with the charisma of Ahab and the seafaring skill of William Bligh, yet refreshingly sane and human, turning their talents to the needs of the voyage. Discipline is strict but also wins the devotion of both officers and sailors. Verne’s composition of a sea story in tribute to his late brother becomes doubly comprehensible given the genre’s possibilities for a heroic portrayal of an idealized mariner.

In the first half of The Kip Brothers, the James Cook has a captain to match the ship’s name. The constant repetition of the name of the ship around which so much of the action revolves serves as a reminder of one of the true heroes of naval command and exploration, whose achievements filled a nearly a third of the 18th century volume of Verne’s Discovery of the Earth: History of the Great Voyagers and Great Navigators. As captain of the James Cook, Gibson himself comes to stand in for the explorer, murdered on the then-“savage” islands, just as natives are initially suspected of taking Gibson’s life on Kerawara. This was not the first allusion to Cook in the Extraordinary Voyages. Cook, the absent hero of The Kip Brothers, is repeatedly referenced in The Mutineers of the Bounty. Captain Bligh was the lieutenant under James Cook, becoming a discrete signifier in The Kip Brothers when considering that Verne had squeezed his story into the Extraordinary Voyages.

Cook is a marker by which the courage of the Kips, and the depravity of Flig Balt and Vin Mod, may be presented. One of their first thoughts in planning to take the ship is to give it a new name, Pretty Girl, not only because it would thereby be lost to searchers, but because the name James Cook is an ever-present sign of morality along the frontiers.

The strength and wisdom of a command in the sea adventure are measured by the captain's own sense of fairness and mercy. The lack of such an understanding portends disaster. Often there is a heartless officer, with an uncaring attitude toward his crew, whether William Bligh, Wolf Larsen, Ahab, Claggart in Billy Budd, or Flig Balt. Obsessed, they have lost all grasp of human values; they believe their goal on the voyage justifies any act, no matter how ruthless. Such a figure may verge on madness and carries authority to an extreme, whether in the service of empire (Bligh) or on some personal mission of revenge (Larsen and Ahab) or outlawry (Balt and Mod).

Gibson has made a fatal error, in relying on the good character of his bosun, accepting his judgment and recruitment of new sailors. The potential mutineers from the “Three Magpies” are repeatedly frustrated when possible opportunities are foiled by a series of coincidences that make the odds against successful mutiny too great. A truly necessary mutiny in the genre must be the only way to secure the basic human dignity of which the crew has been deprived. This is epitomized by the replacement of Bligh by Fletcher Christian, and not a new, more restrictive hierarchy, such as the one that Balt and Mod propose.

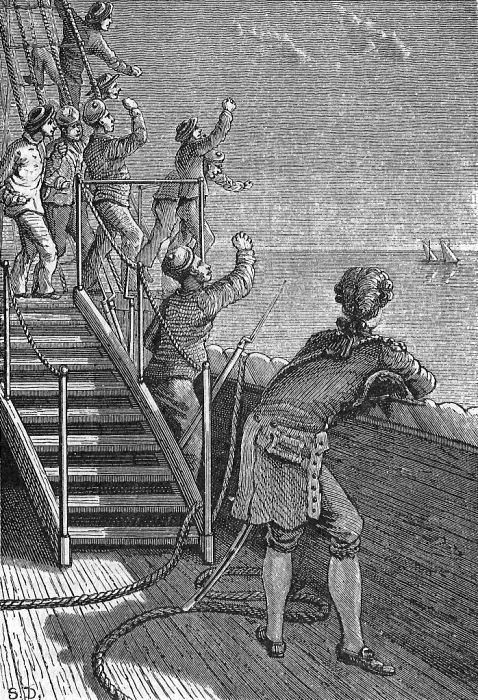

Despite the derivation from Marcel, Verne’s Bounty story was no dry telling of facts and history, but a highly fictionalized account along the lines of the famous 20th century trilogy by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall. Like their series, Mutiny on the Bounty, Men Against the Sea, and Pitcairn’s Island, Verne’s three chapters follow these central strands. The opening tells of Christian seizing the ship and placing Bligh and his followers in a longboat. The second chapter describes their incredible voyage through the most perilous conditions and privations. The final chapter recounts the mutineer’s settlement of Pitcairn’s Island, not concealing how ill-suited the seamen were to the challenges of their new life. However, ameliorating this is the reprehensible treatment of the innocent men when Bligh returned to Tahiti.

Balt’s lack of moral authority is echoed by his mishandling of the ship during a storm. Even as problematic a captain as Bligh had a redeeming quality, the seamanship that steered his followers through a 3,600 mile journey in treacherous seas to port. When Hawkins replaces Balt with Karl Kip as captain, he stands out as the individual who has Gibson’s virtues, righteousness and skill, and so is fit to take the helm of the James Cook. Kip, in effect, not only replaces Gibson as captain, but inherits his mantle as stand-in for Cook, and the Kip brothers will suffer a fate almost as savage as that which their predecessors met, save that they survive.

In both The Mutineers of the Bounty (its first chapter), and The Kip Brothers (197-198), the story is less about the mutiny itself than its lingering aftermath. Whereas the former mutiny was necessary, and in The Kip Brothers a crime, the Fenians are in a position similar to Christian’s followers. Like the mutineers, the Fenians must escape in order to find safety in their struggle for freedom and independence. No less than the refugees settling Pitcairn, the Fenians must flee Old World values and social barriers, transcending them in exile in the United States.

For all these reasons, I would suggest that The Kip Brothers needs to be seen within the context of the sea adventure, and that not only may it reflect on the cases of Dreyfus and the Roriques–and that of Grousset as well–but that this generic structure is ideal for relating such a narrative. Questions of justice and abuse of authority, so much a part of the unjust imprisonment in The Kip Brothers, are central to the sea adventure. Verne had already included the Bounty story in the Extraordinary Voyages and The Kip Brothers resembles it just as it does the more contemporary real-life examples. The author’s selection of genre, and how its formula serves his purposes in telling a story, is central to understanding the many threads that form the tapestry of The Kip Brothers.

NOTES

- An analysis of this plot device within the contemporary beliefs of the time is offered in Arthur B. Evans, “Optograms and Fiction: Photo in a Dead Man’s Eye,” Science-fiction Studies, 20 (November 1993), 341-361.^

- Jean-Michel Margot, “Notes” in Jules Verne, The Kip Brothers (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007), 428-429. Subsequent references to quotations will be from this edition, as translated by Stanford L. Luce.^

- The fraternal relationship in “The Fate of Jean Morenas” was the addition of Michel Verne to his father’s original story.^

- Russell Freedman, Jules Verne: Portrait of a Prophet (New York: Holiday House, 1965), 231.^

- G.A. Raper, “The Story of the Brothers Degrave,” The Wide World Magazine, 7 (June 1901), 211-212.^

- While Jules Verne had several collaborators as a playwright, outside of his own son, Michel, Grousset was the only individual with whom he coauthored novels.^

- Fluent in English, he was often engaged in translations and also wrote a series of pioneering science fiction novels. These included such topics as interplanetary travel and undersea exploration in The Conquest of the Moon (1889), New York to Brest in Seven Hours (1890), The Crystal City Under the Sea (1896), and The Secret of the Magian; or, the Mystery of Ecbatana (1897). Like Verne, Grousset also wrote adventure.^

- Hayden W. Ward, "The Pleasure of Your Heart: Treasure Island and the Appeal of Boys' Adventure Fiction," Studies in the Novel, 6 91978), 314; Robert Kiely, Robert Louis Stevenson and the Fiction of Adventure (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1964), 154 155; Martin Green, Dreams of Adventure, Deeds of Empire (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979), 23. See also William Bolitho, Twelve against the Gods: The Story of Adventure (New York: Readers Club, 1941), 238 9, 214-215; Lowell Thomas, ed., Great True Adventures (New York: Hawthorne, 1955), xi; Georg Simmel, "The Adventure," trans. David Kettler, in Kurt H. Wolff, ed., Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and Aesthetics (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 243; Michael Nerlich, The Ideology of Adventure: Studies in Modern Consciousnes, 1100 1750, trans. Ruth Crowley (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 3, 373. For more background on adventure and its definition, see Brian Taves, The Romance of Adventure: The Genre of Historical Adventure Movies (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993).^

- Paul Zweig, The Adventurer (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), 12.^

- Verne's twenty-nine adventure novels include, chronologically, The Count of Chanteleine: Episode of the Revolution, The Children of Captain Grant, A Floating City, The Blockade Runners, Adventures of Three Russians and Three Englishmen in Southern Africa, Around the World in Eighty Days, The Fur Country, Uncle Robinson, The Chancellor, Michael Strogoff, A Fifteen Year Old Captain, The Jangada, The Archipelago on Fire, A Lottery Ticket, North Against South, The Road to France, Two Year Holiday, Family Without a Name, Caesar Cascabel, Mistress Branican, Claudius Bombarnac, Wonderful Adventures of Master Antifer, The Mighty Orinoco, Second Fatherland, The Kip Brothers, Scholarships for Travel, The Lighthouse at the End of the World, The Golden Volcano, and The Survivors of the Jonathan.^

- Susanne Howe, Novels of Empire (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1949), 64 68.^

- By 1880, Verne stories were mainstays of Boy’s Own Paper in England, promulgating the values of hero worship, militarism, nationalism, and imperialism to youth. As with publication of Verne in the Magasin d’Éducation et de Récréation, serving as a staple in a periodical was at least as important commercially in the 19th century context as actual book sales. American publishers came to rely more and more on utilizing translations already commissioned for Boy’s Own Paper, rather than their own. In turn, British publishers were fearful of Verne stories that might offend Boy’s Own Paper readers in the empire, and so the anticipated taste of this market came to govern what appeared in English translations on either side of the Atlantic. Although one or more Verne titles continued to be published annually in France until 1910, after 1898 only two of these books, The Will of an Eccentric and The Chase of the Golden Meteor, appeared simultaneously in England. Commercial factors were not decisive; while sales in France of the late Verne works declined in the 1890s, they remained profitable in England and the United States, as indicated by the steady issuing of new editions of even such minor novels as Claudius Bombarnac. Even after World War I, to the late 1920s, Sampson Low continued to reprint of many of the lesser known Verne works. Political questions became the deciding factor in whether the latest Verne books appeared in English at all. Their tenor was less agreeable to English speaking audiences, or at least publishers who were not prepared to faithfully present Verne's views. The censorship grew beyond simply changing or removing controversial passages, to avoiding novels where contentious subject matter was embedded.^

- Jean-Michel Margot, “Introduction” in Jules Verne, The Kip Brothers (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007), x.^