Verne’s first visit, 1878

At noon on Wednesday 19th June 1878, the steam yacht Saint-Michel III anchored at Gibraltar. The Saint-Michel was the pride and joy of Jules Verne, then aged 50, and at the height of his fame and fortune. It was a magnificent iron vessel of almost 70 tons, 107 feet in length and only two years old. In addition to a two cylinder engine driving the yacht’s screw, the twin masts carried a powerful set of sails. She was capable of a speed of 11 knots. With a crew of ten and comfortable passenger accommodation, the Saint-Michel was ideally equipped for long distance cruising in Europe and the Mediterranean.

The Garrison newspaper, The Gibraltar Chronicle, announced her presence on Thursday 20th June as follows:

“R.Y.C. steamer St. Michel (J.Verne, Esq., owner on board), Mr E David [captain], 4 hours from Tangiers – cleared to Sea”.

The Saint-Michel had arrived on the short crossing from Tangiers to make a sightseeing visit before continuing the voyage to Malaga, Tetouan, Oran and Algiers. Verne was accompanied by his brother Paul and the captain was E. David, the first captain of the yacht before being succeeded in 1879 by Charles-Frédéric Ollive.

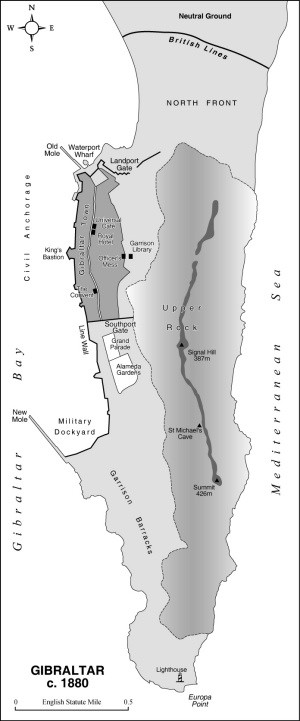

Verne disembarked by ship’s boat to Waterport Wharf to clear customs and quarantine and then strolled along the Line Wall fortifications and visited “The Convent”, the Governor’s official residence, to pay his respects to the Governor, Lord Napier of Magdala (see Map 1). On his voyages, Verne made a habit of calling on local dignitaries and French diplomats. As there was only a handful of permanent French residents, and given that Gibraltar had a colonial rather than a national status, there was no French diplomatic representation. Verne had always been fascinated by fortifications and cannons and continued his exploration along the Line Walls as far as the Southport Gate. From here he was drawn to the sound of military music on the Grand Parade Ground and spent some time listening to the band and enjoying the Alameda Botanic Gardens. The band would have been either that of the 4th Regiment Black Watch or the 7th Regiment Highland Light Infantry, both of which were based in the garrison at that time. The bandstand was located on the site of the present cable car station and the fire brigade, the remainder of the former parade ground being occupied by parking and by housing, reflecting the shortage of space for development in the town.

Verne next made his way back into the town along Main Street as far as the bustling market area around Commercial Square, the “piazza”. Here his eye was drawn to the handsome four storey façade of the newly-opened Royal Hotel opposite the Exchange, where table d’hôte dinner was served at 7pm. Over the decades, the hotel deteriorated in terms of its clientele, becoming popular with sailors in particular, attracted by the cabaret artistes, but fortunately has been preserved and renovated and is currently a fashion boutique.

After dining, Verne made his way back to the Saint-Michel and was aboard by 10pm. It had been a long day, involving an international voyage and several hours exploring Gibraltar on foot. The following morning, having already been cleared to sail by the Captain of Port, Verne set sail early for Oran in Algeria in poor weather which delayed his arrival there until the 22nd June. So ended his first visit to Gibraltar. It had been a rapid reconnaissance, but it had stimulated his literary imagination.

The second visit, 1884

Six years elapsed before Jules Verne once more anchored at Gibraltar. This was his second Mediterranean cruise and was his last voyage aboard the Saint-Michel before selling her, most probably as a result of the high cost of maintaining the boat and its large crew at a time when his income from royalties was declining. He left the port of Nantes on 13th May, 1884 and in bad weather only reached Vigo on the 18th. After engine repairs he anchored at Lisbon on the 22nd. From there Verne hoisted sail on the 25th and made rapid progress to Gibraltar, arriving at 4 in the afternoon. His diary comments on the lighthouse on Europa Point and the presence of a German gunboat on the anchorage. This was in fact the Möwe, commanded by Captain Hoffman which had also arrived from Lisbon. Although not mentioned by Verne, three French commercial vessels were at anchor, from Oran, Naples and Tangier respectively. Once again, The Gibraltar Chronicle recorded Verne’s arrival in its supplement of Monday 26th May.

“French steam yacht St.Michel (J.Verne, Esq. owner, on board). Mr C Ollive [captain] 12 days from Nantes and 2 ½ from Lisbon – cleared to Sea”.

Verne stayed aboard the Saint-Michel and his carnet accurately records the firing of the cannon at 7.45pm warning of the imminent closure of the Landport Gate to Spain. He admired the view of the site of Gibraltar in the evening and resolved to revisit the town the following day.

Landport Wharf, 1878, showing in the foreground the customs

and police controls and, in the distance, coal

hulks

Rising early, as was his practice throughout his life, Verne headed for Main Street, the principal artery of the garrison town, where he remarked on the motley crowd. He noted the veiled women, women with handkerchiefs on their heads, Arabs, Moroccans and Africans, together with British soldiers. Once more he visited the Alameda Gardens and inspected the batteries. He returned along Main Street pausing at the Universal Café for an afternoon tea. Unlike the neighbouring Royal Hotel building which still stands, the Universal Café, a two storey building which stood opposite the Speed Wine Merchants shop which still exists, has disappeared and has been replaced by a modern building. Returning to the Saint-Michel, Verne took on coal for the next leg of his cruise, which was to take him to North Africa, Malta, where he was almost shipwrecked, and to Rome, where he and Mme Verne were received by Pope Leo XIII on 7th July before continuing the return to France by railway.[4]

On deck at 10 on the morning of the 26th, Verne set sail at 11. Rounding Europa Point, Verne marvelled at the vertical Eastern flank of The Rock with its glacis of eroded rock. He wrote ecstatically in his carnet that there was no finer sight in the world! At some stage in his visit he had seen the apes and in his diary makes a note to himself : “Gibraltar captured by the apes. A short story to write”. This he did three years later with the title Gil Braltar.[5] We can thus date the provenance of this short story exactly as the 26th May 1884 at approximately 11.30am!

Gil Braltar is the name given by Verne to a minor and demented Spanish nobleman unable to accept the capture of The Rock by Britain. He is portrayed as having pronounced ape-like features and virtually lives like one in the scrub and caves, including the cavernous St Michael’s cave. Because of his name, he considers that he is entitled to own The Rock and to this end, dons an ape skin and leads a rebellion of the apes against the General in charge of the garrison, General MacKackmale.[6] In the resulting struggle, Gil Braltar is captured and the apes beat a retreat along Main Street, through the South Gate and return to their hill. Their leader is not an escaped Gil Braltar but the general himself. He has put on the captive’s ape skin, and in the semi darkness is undistinguishable from him. The deception is all the more effective as General MacKakmale also has ape-like features! The conclusion drawn by Verne is that the British Government has managed to secure its hold on The Rock by always sending the ugliest possible generals to command the Garrison so that the apes would confuse them with their leader!

In spite of this rather wicked little story, Verne found much to admire in Gibraltar. Although Verne found warfare and political turmoil disturbing, he was fascinated by the heavy weaponry and the strong fortifications[7] and on reaching Malta carried out a similar examination of the defences there.

M. Allotte de la Fuÿe’s version of the 1884 visit

In her biography of Verne, M. Allotte de la Fuÿe claims that on his arrival in Gibraltar, Verne was enthusiastically greeted by officers of the garrison and taken to their mess, returning to the Saint-Michel inebriated and unsteady on his legs after consuming numerous cocktails.[3] The Gibraltar Chronicle, founded in 1801, was essentially the garrison’s newspaper, yet beyond the bland facts of the arrival of the Saint-Michel and her clearance for departure, there is no mention of Verne’s visit in 1884. The only evidence she produces for this is the alleged exercise book diary kept by Verne’s nephew Maurice who was a passenger, along with his father Paul Verne, aboard the Saint-Michel. For a number of reasons this episode seems highly unlikely and not least because in his carnet Verne states that he remained on board on the evening of 25th May. It must be stressed that Gibraltar was not a conventional port. It was a military garrison with an anchorage and after a history of sieges by the Spanish (and the French), strict military control was enforced. Similarly, the importance of quarantine clearance reflected the prevalence of epidemics. In fact, in 1884 there was a cholera epidemic in France and so the Saint-Michel would have been carefully scrutinised. Verne records the firing of a cannon, probably from the King’s Bastion saluting base, at 7.45pm. This warns the population that the Landport Gate, the controlled access point between Gibraltar and Spain, would soon close. Once closed the key was taken to the Governor and was in fact his badge of office and features on Gibraltar’s coat of arms. Thus any Gibraltarians in the North Front would need to enter the town and people without permission to reside in Gibraltar would be obliged to leave. Verne refers to the cannon as the “First Gun” in Gil Braltar. Non-Gibraltarians, like Verne, would have required a special permit to be ashore in the evening and after mid-night a virtual curfew was installed and anyone in the streets was required to carry a lamp so that they could be identified by patrols. The Military Orders books, a substantial vade mecum of local orders applying to the garrison, indicate that members of the military were no less subject to rigid discipline than the civilian population.[8] Controls on the use of alcohol in particular were very strict and although several officers’ messes existed, the notion of Verne being involved in excessive drinking is unlikely. The most central mess was opposite the Garrison Library (which was also used for entertaining). Although Verne would probably have been accorded a pass if requested for him by officers, he would have needed to have been rowed ashore from the Saint-Michel to Waterport Wharf and returned again by ship’s boat, being subject to inspection by guards on both occasions. The main officer’s mess was located quite close to the Governor’s Residence and would have been in a heavily patrolled area of the garrison. Allotte de la Fuÿe’s account seems to give the impression of Gibraltar being a port, where civilians could just walk ashore at will. Nothing could be further from the truth. Gibraltar at that time was essentially a military garrison, with a relatively small and controlled civilian population of approximately 15,000.[9] Apart from the trade to supply the Garrison, especially cattle from Morocco and fruit and vegetables from Spain and Portugal, many of the commercial vessels would simply call to take coal onboard. This was achieved by tying up to hulks and coal would be taken aboard in baskets by “coal haulers” using gangplanks to move from one vessel to the other. Verne coaled the Saint-Michel on both his visits to Gibraltar.

Further doubt can be cast on the Allotte de la Fuÿe version by the fact that a relatively banal supposed event in Gibraltar was recorded in Maurice’s diary whereas the much more dramatic events at Malta, in which Maurice was directly involved, which would surely have been recorded in his diary, are not even mentioned in her biography. Similarly, the happenings at Sidi Yussef Bay on Cap Bon Tunisia, are recorded in Verne’s carnets as mild horseplay rather than an encounter with threatening “Senussi” tribesmen. The supposed diary written by Maurice Verne has not been found in the public domain. If such a written document exists, a plausible theory is that it might have been a letter written by Maurice, to his mother perhaps, and that as an impressionable youth accompanying a world famous author, he may have exaggerated his account. It is also well known that Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe had a propensity to invent dramatic effects.[10] Until such time, if ever, that Maurice’s diary is discovered, the authenticity of her account can only be evaluated by juxtaposing it with Verne’s own entry in his carnet to the effect that he remained in the Saint-Michel at the time when he was supposedly carousing with British officers.

Conclusion

In spite of the malicious portrayal of the British in Gil Braltar, Verne found much to admire in Gibraltar. Although having a distaste of disorder and war, Verne was fascinated by the weapons and accoutrements of warfare. The fortifications and batteries of Gibraltar were immense and impregnable and were matched by an equally strong internal control of the diverse population and visiting commercial traders from Spain and North Africa. The vertical east face of the Rock, with its glacis of eroded sand, impressed Verne as one of the most beautiful sights he had ever seen. We can assume that Gil Braltar was at least partially written tongue in cheek as a satire rather than as an intentionally offensive attack. Finally, no evidence has been found to sustain the claim that Verne enjoyed hospitality to the point of inebriation at the officer’s mess.[11]

NOTES

- Olivier Dumas, Jules Verne et Gibraltar, Jules Verne, l’Afrique et la Méditerranée, (Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 2005), 59–65.^

- Gil Braltar, (Paris: Hetzel, 1887).^

- Allotte de la Fuÿe, M., Jules Verne, sa vie, son oeuvre, (Paris: Hachette, reedition, 1953).^

- Thompson, I.B. and Valetoux, Ph., La visite de Jules Verne à Malte en 1884, Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, No 159, 2006, 42–47. The fact that the Saint-Michel took on coal on both visits to Gibraltar reflected the limited capacity of coal storage on board. The coal available at Gibraltar would have been of good quality because of the needs of the Royal Navy.^

- Alain Braut has shown that an earlier version of Gil Braltar< was published in Le Petit Journal du Dimanche, No 134, 1887, with slight variations as compared with the Hetzel edition.^

- In fact the “apes” are macaques, tail-less monkeys originating in Morocco, Macaca sylvanus. In naming the British general “Mac Kackmale”, it is widely accepted that Verne is offensively referring to him as a male monkey (macaque mâle)!^

- The fortifications were established during the Moorish occupation lasting over six centuries. The British elaboration of the fortifications in the nineteenth century was in part achieved by convicts despatched from Britain. For views of the fortifications and Gibraltar in general at the time of Verne’s visits, see the remarkable large photographic collection made by George Washington Wilson held by the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, which can be viewed on line (University of Aberdeen Photographic Archive, key word George Washington Wilson Collection).^

- General Regulations and Standing Orders for the Garrison of Gibraltar, established by Lt. General Sir Alexander Woodford, Governor, and printed at the Garrison Library.^

- H.W. Howes, The Gibraltarians, (Gibraltar: Medsun, 3rd Edition, 1991).^

- See, for example the comments by Weissenberg and by Maudhuy. Weissenberg, E., Jules Verne un univers fabuleux, (Lausanne: Favre, 2004) 28–33. Maudhuy, R., Jules Verne. La face cachée, (Paris: France-Empire, 2005) 69–70.^

- Details of Verne’s voyages to Gibraltar were provided by Philippe Valetoux, (see Philippe Valetoux, Jules Verne en mer et contre tous, Magellan, Paris, 2005).^

Verne’s Carnets de Voyages are held by the Municipal Library at Amiens, (Ms 101440095, Saint-Michel). Archival and field work in Gibraltar was conducted by Ian Thompson.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable help of the following persons in Gibraltar; Lorna Swift (Librarian of the Garrison Library), Professor Clive Finlayson and Dr Darren Fa (Gibraltar Museum), Dominique Searle (Editor, Gibraltar Chronicle) and Tito Benady (Historian and Publisher). The accompanying photograph in this article is reproduced by kind permission of the Gibraltar Museum.